Posts Tagged ‘Jefferson Davis’

Stephen Woodworth to Teach Civil War Command and Leadership

I just registered for my next course: Civil War Command and Leadership. Here’s a quick summary: “a study of national, theater, and operational command structures of the Union and Confederacy, the leadership styles of key military leaders on both sides, and the evolution of command and control in the war. Major themes include the relationship between the commanders in chief and the generals who led the armies in the field, the relationships between the generals themselves, and the ways in which the relationships described above either served to facilitate or debilitate the causes those commanders served.”

I am VERY excited about the professor, Steven E. Woodworth!

- Ph.D., Rice University, 1987

- Professor of history at Texas Christian University

- Author, co-author, or editor of twenty-seven books you can view here

- Two-time winner of the Fletcher Pratt Award of the New York Civil War Round Table (for Jefferson Davis and His Generals and Davis and Lee at War)

- Two-time finalist for the Peter Seaborg Award of the George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War (for While God Is Marching On and Nothing but Victory)

- Winner of the Grady McWhiney Award of the Dallas Civil War Round Table for lifetime contribution to the study of Civil War history

I’ve added a new page on my bookshelves to show the booklist for the course as it stands today which you can access here.

Free or Inexpensive American Civil War Titles for Kindle

I’ve spent some time at the Kindle Store perusing their books for deals on American Civil War Books. I’ll follow up with additional lists on Military History and History in general although they are numerous. One plus – many of the Army Field manuals are available for $0.99, You could, of course, download most of the latter from other sites and load to you Kindle as well.

Of note, David Woodbury over at of Battlefields and Bibliophiles has posted an outstanding piece on the digitalization of books phenomena which you can read here.

Here’s my list so far of ACW books that are free or under $2.00 in the Kindle Store. Bear in mind that most of these are in the public domain so you can also load them to your Kindle 2 for free in the manners I described in previous posts.

General Histories

History of the Civil War, 1861 – 1865 by James Ford Rhodes $0.99

Memoirs and Biographies

Sheridan

Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan, General, United States Army Volume 1 by Philip Henry, General, 1831-1888 Sheridan – $0.00

Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan, General, United States Army Volume 2 by Philip Henry, General, 1831-1888 Sheridan – $0.00

Personal Memoirs of P.H. Sheridan, both volumes in one file by Philip Henry Sheridan – $0.99

Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant Volume 1 by Ulysses S. (Ulysses Simpson), 1822-1885 Grant – $0.00

Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant Volume 2 by Ulysses S. (Ulysses Simpson), 1822-1885 Grant – $0.00

Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant by Ulysses S. Grant and Mark Twain- $0.99

Letters of Ulysses S. Grant to His Father and His Youngest Sister, 1857-1878 by Ulysses S. Grant and Jesse Grant Cramer – $0.99

Campaigning with Grant (1907, [c1897]), First Person Account of Ulysses S. Grant During the Civil War by Horace Porter – $1.59

Stonewall Jackson

Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War, both volumes in a single file by Colonel G.F.R. Henderson – $0.99

Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War by G. F. R. Henderson – $0.99

Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War by G.F.R. Henderson and Viscount Wolseley – $0.99

Lee

The Life of General Robert E. Lee by Captain Robert E. Lee (his son) – $0.99

A Life of General Robert E. Lee by John Esten Cooke – $0.99

Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee by his son by Captain Robert E. Lee – $0.99

With Lee in Virginia, a Story of the American Civil War by G.A. Henty – $0.99

W. T. Sherman

Memoirs of General William T. Sherman by William T. Sherman – $0.99

Thirteen Months in the Rebel Army by William G. Stevenson – $0.99

Captains of the Civil War – A Chronicle of the Blue and the Gray by William Wood – $0.99

Military Reminiscences of the Civil War, both volumes in a single file by Jacob Dolson Cox – $0.99

Military Reminiscences of the Civil War, Volume 1 by Jacob Dolson Cox – $1.84

Military Reminiscences of the Civil War, Volume 2 by Jacob Dolson Cox – $1.84

Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops by Joshua M. Addeman – $0.99

Army Life in a Black Regiment by Thomas Wentworth Higginson – $1.00

Heroes of the Great Conflict: Life and Services of William Farrar Smith, Major General, United States Volunteer in the Civil War by James Harrison Wilson – $0.99

The Scouts of Stonewall: The Story of the Great Valley Campaign by Joseph A. (Joseph Alexander), 1862-1919 Altsheler

The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government by Jefferson Davis

Regimental Histories

History of Company E of the Sixth Minnesota Regiment by Alfred J. Hill – $1.59

Women

Woman’s Work in the Civil War; A Record of Heroism, Patriotism, and Patience by M.D. L. P. Brockett – $1.80

Memories: a Record of Personal Experience and Adventure During Four Years of War by Mrs. Fannie A. Beers – $0.99

Fortifications and Armaments

A History of Lumsden’s Battery, C.S.A. by Dr. George Little and james R. Maxwell – $1.99

History of the Confederate Powder Works by George W. Rains- $1.19

Naval

![the-fight-between-the-alabama-and-the-kearsarge-nh59354 "The Fight Between the Alabama and the Kearsarge" [NH59354]](https://wigwags.files.wordpress.com/2008/09/the-fight-between-the-alabama-and-the-kearsarge-nh59354.jpg?w=700)

The Story of the Kearsarge and the Alabama by A. K. Browne – $0.99

The Cruise of the Alabama and the Sumter, both volumes in a single file by Raphael Semmes- $0.99

Railroads

The Great Railroad Adventure – a True Tale from the American Civil War by Lieut. William Pittenger – $0.99

Prisons

Andersonville: a Story of Rebel Military Prisons, all four volumes in a single file by John McElroy – $0.99

Other Biography

John Wilkes Booth

The Life, Crime & Capture of John Wilkes Booth by George Alfred Townsend – $0.99

Speeches and Legislative Documents

Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address by Abraham Lincoln – $0.49

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln – $0.49

The Emancipation Proclamation (Preliminary and Final Version) by Abraham Lincoln and William Seward – $0.80

Jefferson Davis’ Inaugural Address by Jefferson Davis – $0.99

Civil War Photography

Taking Photographs During the Civil War – $0.80

Fiction

The Little Regiment and Other Episodes of the American Civil War by Stephen Crane. Published by MobileReference (mobi) by Stephen Crane – $0.99

The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane – $0.99

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part III

This post completes the series, Stewards of Civil War Railroads. Read Part I here and Part II here.

Above: Group of the Construction Corps U.S. Mil. R. Rds., with working tools, etc., Chattanooga, Tennessee

Courtesy of Library of Congress: LC-USZ62-62364

Millett and Maslowski posit that President Abraham Lincoln did not have Jefferson Davis’ sensitivity about government interference with railroads. The evidence supports the point and also suggests that Davis’ hands-off approach expanded to other areas under his purview including signals and communications. Whether he was afflicted with chronic indecisiveness or was bowing to the perceived whims of a public unreceptive to “big government” is open for discussion but as in many things, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Regardless, it is clear that rational military considerations were not the sole concern in shaping the South’s military policies and programs. Had they been so, military needs would have received higher priority and the events of the war may have flowed differently.

Above: Lincoln and McClellan

The impact of the decision making processes in the Lincoln and Davis administrations and the respective Congresses as regards those issues impacting the military is indeed a fascinating one and worthy of continued analysis and review. Clearly the social, economic, and political nuances of the North versus the South had much to do with the directions taken within each section. But one is left to wonder whether the leadership qualities of Lincoln and Davis, including the ability to be decisive, allowed the North to more frequently follow a path guided by rational military reason.

Above: The engine “Firefly” on a trestle of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part II Davis

This post continues from Part I, here.

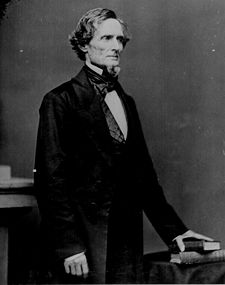

Jefferson Davis (above) and the Confederate Congress, by contrast, were reluctant to wrestle control of the railroads away from civilian owners. This was consistent with a laissez faire pattern exhibited by Davis on a number of issues involving civilian commercial interests and may have been a response to the populace’s opposition to overbearing centralized government. The consequences were dire for Lee. In the winter of 1862, he found his Army of Northern Virginia completely reliant on its communications. [i]

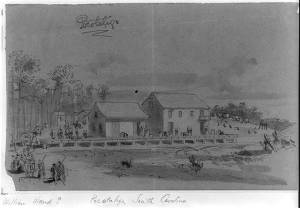

Above: Pocotaligo, South Carolina – Railroad depot center of image surrounded by rough sketch of soldiers and covered wagons. Circa: 1865

Medium: 1 drawing on tan paper : pencil, black ink wash, and Chinese white ; 14.7 x 21.4 cm. (sheet).

Source: Library of Congress Ref: LC-USZ62-14306 (b&w film copy neg.)

With the mobility, indeed the survival, of the army dependent on the efficient use of the railroads, the railroad owners responded with an assertion of their individual rights. They failed to cooperate. Government shipments were accorded low priority. The railroads over which the animals’ feed had to be transported refused to use the space for bulk fodder. The breakdown of the railroad system led to a crisis in the supply of horses, mules, fodder, and subsistence. The Army of Northern Virginia was left hanging at the end of its lines of communications.[ii]

Above: Warrenton Depot, on the Orange & Alexandria RR, in August 1862. Supply point for Lee.

Davis’ refusal to give greater control to the military for operation of the railroads added to “the weight of this burden of waging war by improvisation within the confines of the Confederacy’s social and political ideals [and] helped break the back of Confederate offensive power.” [iii]

Edward Hagerman notes that problems continued into 1863 as “conflicts between the commissary agents of field commanders and those of the [Confederate] Subsistence Department hampered efficient gathering of available resources.” [iv] The largest obstacle was “the failure of the railroads to cooperate in the distribution of food surpluses from other states to the Army of Northern Virginia. Neither the army nor the government exercised any control over the railroads.” [v] It wasn’t until Lee’s army was faced with starvation that the Confederate Congress intervened. In April of 1863, it “hesitantly” granted Jefferson Davis the “authority to regulate the railroads.” [vi]

The laissez faire-minded Davis was as reluctant to accept the authority as the Confederate Congress was to bestow it. Here was the instrument to prevent a recurrence of the crisis of the past winter. It would enable through scheduling the interchange of rolling stock from one railroad to another. It also would enable the War Department, rather than the railroad owners, to decide on the priority of material to be transported. [vii]

Davis signed the bill into law but Congress ensured its ineffectiveness by failing to approve an “office of railroad superintendent” as proposed by the secretary of war and by sacking the temporary appointee. [viii] “Not until early 1865, far too late, did the Confederacy finally take control of the railroads.” [ix]

[i, ii, iii] Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 121.

[iv, v] Ibid., 130.

[vi, vii, viii] Ibid., 131.

[ix] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, 165.

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part I Lincoln

The decisions made by leaders of the North and South regarding the dispensations of their respective railroads, could arguably be some of the most impactful of the war. Armies on both sides considered railroads critical. But Lincoln and Davis approached the control and stewardship of these vital resources differently. The resulting policies did not equally reflect rational military consideration.

Above: United States Military Railroad 4-4-0 locomotive W.H. Whiton (built by William Mason in 1862) in January 1865 with Abraham Lincoln’s presidential car, which later was used as his funeral car.

Source: Wikicommons

The need for oversight of the rails came early in the war. Edward Hagerman highlights Federal Quartermaster General Meigs’ complaints in the opening months of the war over the problems of coordination that arose “from civilian control of the railroads.” [i] In January of 1862, Congress gave Lincoln the authority he needed “to take control whenever public safety warranted it.” [ii] Lincoln moved decisively, appointing within thirty days Daniel C. McCallum (below) as director of the United States Military Railroads (USMRR).

Daniel C. McCallum (1815 – 1878)’

Photo Source: Wikicommons, Public Domain

In May of 1862, Abraham Lincoln “took formal possession of all railroads.” General McCallum recruited Herman Haupt (below), a “brilliant railroad engineer,” to assume duties as Military Director and Superintendent of the United States Military Railroad. Haupt was given the rank of Colonel and Lincoln gave him broad, albeit frequently challenged, powers.

Henry Haupt (1817 – 1905)

Military Director and Superintendent of the united States Military Railroad

In the next post, the action of the South.

You may also be interested in two of my previous posts on Civil War Railroads:

[i] Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 63.

[ii] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 165.

Straight talk on soldiers and presidents

I’m reading The Cause Lost: Myths and Realities of the Confederacy by William C. Davis. The approach Davis has taken is to profile the primary players in the conflict – foibles and all. W. C. presents a fascinating portrait of Jefferson Davis which borders on being psychoanalytic. It helps to explain why Davis and his generals had such poor relationships, the exception being Lee who was a master at determining how to handle the man and won his loyalty and friendship. Three of Lee’s practices stood out. First, he kept Davis informed on a daily basis – unlike Beauregard and Johnston. Second, he asked Davis for his opinion, which stroked his ego. Third, he stayed away from the press and didn’t criticize Davis behind his back. Lee’s peers struggled with either their own self-importance or lack of ability and found outlet by back-biting in the press.

All in all a very good read largely because Mr. Davis pulls no punches. Also worth the read because of the details provided; case in point, the sinking of the “Stone Fleet” at the mouth of the harbor leading into Charleston. This strategy by the Federals to block traffic in and out of the harbor failed miserably due to the soft mud bottom into which the fleet – whose holds were filled with granite – sank.

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

of schools and colleges taught “Southern Nationalism” and impressed on the minds of students the “standard ‘line’ on the issues of slavery, politics, and economics.”

of schools and colleges taught “Southern Nationalism” and impressed on the minds of students the “standard ‘line’ on the issues of slavery, politics, and economics.”