Archive for the ‘Railroads’ Category

On General Grenville M. Dodge

One of my readers is researching General Grenville M. Dodge and asked for information. I, of course, turned promptly to my buddy Peter A. Hansen who knows more about rail history than anyone I know. Pete writes for most of the major rail history magazines, consults with museums and rail companies, speaks regularly on rail history, and is currently editor of Railroad History, the scholarly journal of the Railway and Locomotive Historical Society. Pete has also been an on-camera source for CBS News and NBC News. More about Pete here.

Fun Fact: It’s an indisputable fact that Railroad History is the oldest (and still the most scholarly) rail history journal, but it is also believed to be the oldest industrial heritage journal of any kind in the U.S.

The information below is all Pete’s.

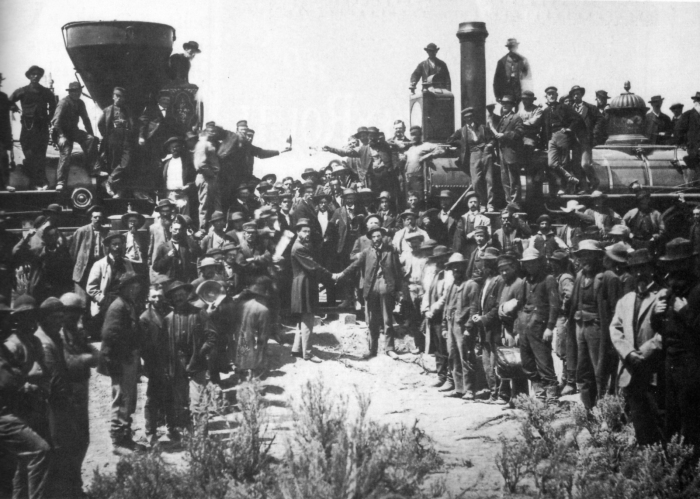

“You’ve seen Dodge many times, though you may not have known it. He appears at the center of what’s arguably the most famous photograph in American history (below). Two men on the ground are shaking hands; Dodge is the one on the right.

Golden Spike ceremony; 16-G-99-1-1, Still Picture Records; Photographs and other Graphic Materials; Records of the Office of the Secretary of Agriculture; Record Group 16; National Archives.

Dodge was born in Danvers, Mass. in 1831, and educated at New Hampshire’s Durham Academy and Vermont’s Norwich University. Upon receiving his engineering degree, he did what many ambitious young engineers did in the 1850s: He went to work for a railroad. He started with the Illinois Central, and later went to the Chicago & Rock Island and the Mississippi & Missouri. It was during his service to the latter two roads that he met Thomas C. Durant, who would later become the driving force behind the Union Pacific, the eastern half of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad.

Dodge’s relationship with Lincoln stemmed from a chance 1859 encounter on the front porch of the Pacific House hotel in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Lincoln was in town to inspect some real estate that had been offered as collateral for a loan requested by a friend, and he was also due to make a speech there. (He wasn’t yet an officially-declared candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, but he was at least considering it.) Dodge had just returned from a surveying expedition in Nebraska’s Platte Valley, seeking a route for an eventual Pacific railroad. Lincoln, a frontiersman by birth, was intensely interested in the subject of internal improvements, and particularly in a line to California. During their two-hour meeting, Lincoln did most of the listening, and Dodge, the talking. “By his kindly ways,” Dodge would recall, “[he] soon drew from me all I knew of the country west, and the results of my reconnoisances. [sic] As the saying is, he completely ‘shelled my woods,’ getting all the secrets that were later to go to my employers.”

A few years later, when President Lincoln needed impartial advice on the Pacific Railroad, the greatest non-military undertaking of his administration (or indeed, in all of American history, up to that point), he turned to Dodge. Apart from his unquestioned abilities, it may have been Dodge’s relationship with Lincoln that made him a favorite of Sherman and Grant.

Dodge began the war inauspiciously enough, as colonel of the Fourth Iowa infantry regiment. He was to make his mark at Pea Ridge in early 1862, where he sustained multiple minor wounds and had three horses shot from under him. He was promoted to brigadier general in April of that year, and was commanded to rebuild the Mobile & Ohio Railroad between Corinth, Miss., and Columbus, Ky. Despite continual harassment by Nathan Bedford Forrest, he got the job done by October.

His performance did not go unnoticed. Grant’s chief of staff, John Rawlins, sent for him that month, and he was given a divisional command with the Army of Tennessee. He became something of a spymaster during the Vicksburg campaign, where he also covered Grant’s left during the final stages.

It’s also worth noting that Lincoln sent for Dodge during the Vicksburg siege, seeking his advice on several matters related to the Pacific Railroad Act. In particular, the Act had authorized the president to name the eastern terminus of the line, and Lincoln wanted to hear more about Council Bluffs. Also, certain provisions of the 1862 Act had scared private investors away from the project: Lincoln sought Dodge’s advice on how to redress them, but ultimately rejected Dodge’s advice on the finance question. Dodge thought the government should simply build the railroad itself; Lincoln favored a revised Pacific Railroad Act in which government bonds would take second position to private issues – a reversal from the original Act. Lincoln’s view prevailed in Congress, and a second Pacific Railroad Act was passed in 1864. Lincoln did follow Dodge’s advice about Council Bluffs, however, and to this day, the city is Milepost 0 on the Union Pacific’s line west from the Missouri River.Dodge went on leave after Vicksburg, and Durant lobbied him vigorously to resign his commission and return to railroading. Durant saw an opportunity in the young engineer for unparalleled Washington influence, and offered him the generous salary of $5,000. Nonetheless, Dodge remained in uniform for the rest of the war, though he would never again attain the distinction of the early campaigns. He served under Sherman during the siege of Atlanta, where a bullet fractured his skull, after which he was effectively out of the war.

Incidentally, Dodge’s papers can be found at the Iowa State Department of History and Archives in Des Moines. Do take his writings with a grain of salt: Dodge was not above embellishing his record. His home in Council Bluffs is now a museum, and it’s well worth a visit. While you’re in town, you might also check out the Union Pacific Railroad Museum, which tells the story of the first transcontinental railroad, and of Dodge’s role in it.

Two additional footnotes:

- One of the perks of being a railroad construction engineer, especially in virgin territory, was the ability to name places. Thus, the highest point on the first transcontinental line was at Sherman, Wyo., 8013 feet above sea level. Some 120 miles west, another Wyoming town bears the name of Rawlins.

- Some of Dodge’s history with Lincoln is recounted in my February 2009 Trains magazine feature, ‘The Rail Splitter and the Railroads.'”

————————————————————

Many thanks to Pete for the information above!

For more on Grenville Dodge, I recommend:

- Iowa Public Televisions Series on Dodge here.

- Dodge’s book, How we built the Union Pacific railway: and other railway papers and addresses thanks to Google Books.

Railroad Generalship: Foundations of Civil War Strategy

I ran across an excellent monograph yesterday by Dr. Christopher R. Gabel titled “Railroad Generalship: Foundations of Civil War Strategy.” It is available in its entirety on the Command and General Staff College’s Combined Arms Research Library here. It includes maps and illustrations.

The following is the foreward by Jerry D. Morelock , Colonel, Field Artillery and Director of the Combat Studies Institute.

“According to an old saying, “amateurs study tactics; professionals study logistics.” any serious student of the military profession will know that logistics constantly shape military affairs and sometimes even dictate strategy and tactics. This excellent monograph by Dr. Christopher Gable shows that the appearance of the steam-powered railroad had enormous implications for military logistics, and thus for strategy, in the American Civil War. Not surprisingly, the side that proved superior in “railroad generalship,” or the utilization of the railroads for military purposes, was also the side that won the war.”

Gabel provides some astonishing statistics which illustrate why railroads challenged traditional strategic direction during the Civil War. He contends that the net effect of “the advent of the steam-powered railroad” was a boost in logistical output by at least a factor of ten. The impact on strategy in the Civil War was staggering. “Most notably, the railroad increased enormously the geographical scale of military operations.” Armies got larger. Sherman’s offensive campaign used 100,000 men and 35,000 animals. His supply line consisted of a single-track railroad extending 473 miles from Atlanta to his main supply base at Louisville. Sherman estimated that this rail line did the work of 36,800 wagons and 220,800 mules!”

Civil War Wagons

For those of you really into military strategy, Gabel provides a simple yet effective illustration of “interior lines” and “exterior lines” and why railroads sometimes helped and other times hindered Civil War strategists who tried to use Jomini/Napoleonic concentration on “interior lines” strategy.

Regular followers of Wig Wags will know that I’ve posted on this fascinating topic before. See the page, Civil War Railroads here.

Highly recommend.

Christopher R. Gabel, “Railroad Generalship: Foundations of Civil War Strategy.” http://www-cgsc.army.mil/carl/resources/csi/gabel4/gabel4.asp#org, Accessed: May 24, 2009.

Nightly News video : Railroads woven into presidential history

NBC Nightly News ran this piece tonight. My buddy Peter Hansen (above) is interviewed toward the end. His clip was filmed here in Kansas City behind the headquarters of Kansas City Southern Railway next to what is known as the Harry Truman Car. That would make his second national news program in a week or so. Not bad! See his contributions in my popular series titled Civil War Railroads here.

If the video below doesn’t play, click here or on Pete’s image above.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

“The Rail Splitter and the Railroads”

RUN don’t walk to your nearest bookstore or library to read the cover story of the February issue of Trains Magazine, “The Rail Splitter and the Railroads,” by Peter A. Hansen. This terrific article, written by one of the country’s preeminent rail historians, is receiving numerous accolades. Highly recommend for those interested in 19th century America and the Civil War era.

RUN don’t walk to your nearest bookstore or library to read the cover story of the February issue of Trains Magazine, “The Rail Splitter and the Railroads,” by Peter A. Hansen. This terrific article, written by one of the country’s preeminent rail historians, is receiving numerous accolades. Highly recommend for those interested in 19th century America and the Civil War era.

For those of you who are regular Wig Wags Blog readers, you’ll recall that Pete contributed to my Civil War Railroads series here. If you’re a CBS Sunday Morning fan, and caught the show yesterday, you may have seen Pete interviewed by Rita Braver as a part of the story titled AMERICANA: Trains as Art. Pete took Sunday Morning to Kansas City’s “triple crossing,” as well as to the renovated, grand old Union Station.

Railroad Historian Inteview – Peter A. Hansen – 12/4

My buddy Peter Hansen, who contributed to my series of posts on Civil War railroads here, will be interviewed on the radio program Up to Date Thursday, December 4th from 11 AM – Noon Central Time about the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art special exhibit of Art in the Age of Steam: Europe, America and the Railway, 1830-1960. (I’m hoping we can finagle a personal tour with Pete as guide.) Of note in Pete’s bio below, (which I’ll admit I snagged from KCUR’s website in hopes that they’d appreciate the publicity), is a heads up about a story he’s written for Trains on Lincoln and the railroads. It’s well worth the read when it comes out next year.

Image: Pierre Fix-Masseau, French (1905 - 1994). Exactitude. 1932. Color Lithograph, 39 1/2 x 24 1/2 inches (99.7 x 61.6 cm.) Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the Modernism Collection. Gift of Norwest Bank Minnesota.

11:00 am – Noon, Thursday, December 4, 2008

More than any industry, railroads have made Kansas City a regional metropolis. The story of railroading in this area is a richly human one, populated by important and visionary figures like Octave Chanute, Fred Harvey, and Arthur Stilwell.The industry continues to thrive today, thanks largely to its inherent fuel efficiency, making railroads a green option for the 21st century. But how – and where – did the train industry begin in Kansas City? Today Steve Kraske talks with Peter Hansen, editor of Railroad History, the academic journal of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society. They’ll discuss how railroads impacted Kansas City – how trains permanently changed the land, and the way that people and goods traveled over it. We’ll also talk with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art executive director Marc WilsonArt in the Age of Steam: Europe, America and the Railway, 1830-1960 about the museum’s special exhibit of . The exhibit, on display through January 18th, features more than 100 paintings, prints, drawings and photographs drawn from 64 museums and private collections.

Art in the Age of Steam is the most wide-ranging exhibition ever assembled of American and European works of art responding to the drama of the railroad, from the earliest days when steam trains churned across the landscape through the romance of the Victorian era to the end of the steam era in the 1960s.

Peter A. Hansen is the editor of Railroad History, the academic journal of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, and his work also appears frequently in Trains and Classic Trains magazines. His next Trains cover story will appear in the February 2009 issue. Titled The Rail Splitter and the Railroads, it was done at the behest of the Lincoln Bicentennial Commission in honor of the 16th president’s 200th birthday. Pete was a contributor to the Encyclopedia of North American Railroads, published by

Peter A. Hansen is the editor of Railroad History, the academic journal of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, and his work also appears frequently in Trains and Classic Trains magazines. His next Trains cover story will appear in the February 2009 issue. Titled The Rail Splitter and the Railroads, it was done at the behest of the Lincoln Bicentennial Commission in honor of the 16th president’s 200th birthday. Pete was a contributor to the Encyclopedia of North American Railroads, published by  the Indiana University Press. He is currently research assistant to Bill Withuhn, the transportation curator at the Smithsonian Institution, on an engineering study of American steam locomotive technology.

the Indiana University Press. He is currently research assistant to Bill Withuhn, the transportation curator at the Smithsonian Institution, on an engineering study of American steam locomotive technology.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

For more information about the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art’s exhibit Art in the Age of Steam click here.

Civil War Railroad Page Updated

By way of housekeeping, I’ve updated the Popular Series Posts page on the right nav bar titled Civil War Railroads here with the latest series of posts titled “Stewards of Civil War Railroads.”

Above: United States Military Railroad 4-4-0 locomotive W.H. Whiton (built by William Mason in 1862) in January 1865 with Abraham Lincoln’s presidential car, which later was used as his funeral car.

Source: Wikicommons

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part III

This post completes the series, Stewards of Civil War Railroads. Read Part I here and Part II here.

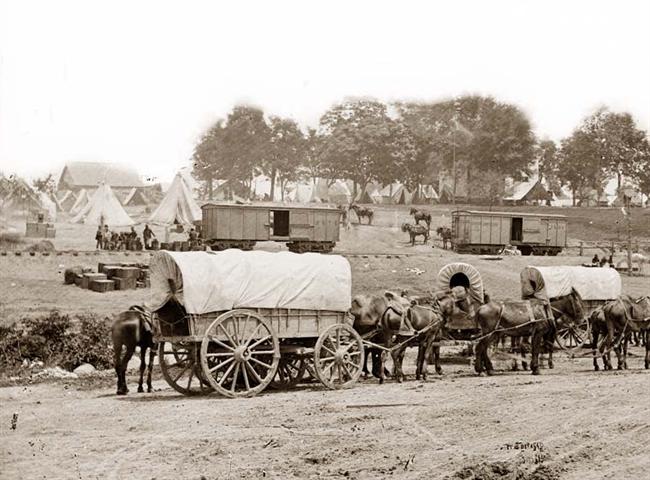

Above: Group of the Construction Corps U.S. Mil. R. Rds., with working tools, etc., Chattanooga, Tennessee

Courtesy of Library of Congress: LC-USZ62-62364

Millett and Maslowski posit that President Abraham Lincoln did not have Jefferson Davis’ sensitivity about government interference with railroads. The evidence supports the point and also suggests that Davis’ hands-off approach expanded to other areas under his purview including signals and communications. Whether he was afflicted with chronic indecisiveness or was bowing to the perceived whims of a public unreceptive to “big government” is open for discussion but as in many things, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Regardless, it is clear that rational military considerations were not the sole concern in shaping the South’s military policies and programs. Had they been so, military needs would have received higher priority and the events of the war may have flowed differently.

Above: Lincoln and McClellan

The impact of the decision making processes in the Lincoln and Davis administrations and the respective Congresses as regards those issues impacting the military is indeed a fascinating one and worthy of continued analysis and review. Clearly the social, economic, and political nuances of the North versus the South had much to do with the directions taken within each section. But one is left to wonder whether the leadership qualities of Lincoln and Davis, including the ability to be decisive, allowed the North to more frequently follow a path guided by rational military reason.

Above: The engine “Firefly” on a trestle of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part II Davis

This post continues from Part I, here.

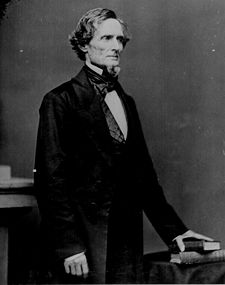

Jefferson Davis (above) and the Confederate Congress, by contrast, were reluctant to wrestle control of the railroads away from civilian owners. This was consistent with a laissez faire pattern exhibited by Davis on a number of issues involving civilian commercial interests and may have been a response to the populace’s opposition to overbearing centralized government. The consequences were dire for Lee. In the winter of 1862, he found his Army of Northern Virginia completely reliant on its communications. [i]

Above: Pocotaligo, South Carolina – Railroad depot center of image surrounded by rough sketch of soldiers and covered wagons. Circa: 1865

Medium: 1 drawing on tan paper : pencil, black ink wash, and Chinese white ; 14.7 x 21.4 cm. (sheet).

Source: Library of Congress Ref: LC-USZ62-14306 (b&w film copy neg.)

With the mobility, indeed the survival, of the army dependent on the efficient use of the railroads, the railroad owners responded with an assertion of their individual rights. They failed to cooperate. Government shipments were accorded low priority. The railroads over which the animals’ feed had to be transported refused to use the space for bulk fodder. The breakdown of the railroad system led to a crisis in the supply of horses, mules, fodder, and subsistence. The Army of Northern Virginia was left hanging at the end of its lines of communications.[ii]

Above: Warrenton Depot, on the Orange & Alexandria RR, in August 1862. Supply point for Lee.

Davis’ refusal to give greater control to the military for operation of the railroads added to “the weight of this burden of waging war by improvisation within the confines of the Confederacy’s social and political ideals [and] helped break the back of Confederate offensive power.” [iii]

Edward Hagerman notes that problems continued into 1863 as “conflicts between the commissary agents of field commanders and those of the [Confederate] Subsistence Department hampered efficient gathering of available resources.” [iv] The largest obstacle was “the failure of the railroads to cooperate in the distribution of food surpluses from other states to the Army of Northern Virginia. Neither the army nor the government exercised any control over the railroads.” [v] It wasn’t until Lee’s army was faced with starvation that the Confederate Congress intervened. In April of 1863, it “hesitantly” granted Jefferson Davis the “authority to regulate the railroads.” [vi]

The laissez faire-minded Davis was as reluctant to accept the authority as the Confederate Congress was to bestow it. Here was the instrument to prevent a recurrence of the crisis of the past winter. It would enable through scheduling the interchange of rolling stock from one railroad to another. It also would enable the War Department, rather than the railroad owners, to decide on the priority of material to be transported. [vii]

Davis signed the bill into law but Congress ensured its ineffectiveness by failing to approve an “office of railroad superintendent” as proposed by the secretary of war and by sacking the temporary appointee. [viii] “Not until early 1865, far too late, did the Confederacy finally take control of the railroads.” [ix]

[i, ii, iii] Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 121.

[iv, v] Ibid., 130.

[vi, vii, viii] Ibid., 131.

[ix] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, 165.

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part I Lincoln

The decisions made by leaders of the North and South regarding the dispensations of their respective railroads, could arguably be some of the most impactful of the war. Armies on both sides considered railroads critical. But Lincoln and Davis approached the control and stewardship of these vital resources differently. The resulting policies did not equally reflect rational military consideration.

Above: United States Military Railroad 4-4-0 locomotive W.H. Whiton (built by William Mason in 1862) in January 1865 with Abraham Lincoln’s presidential car, which later was used as his funeral car.

Source: Wikicommons

The need for oversight of the rails came early in the war. Edward Hagerman highlights Federal Quartermaster General Meigs’ complaints in the opening months of the war over the problems of coordination that arose “from civilian control of the railroads.” [i] In January of 1862, Congress gave Lincoln the authority he needed “to take control whenever public safety warranted it.” [ii] Lincoln moved decisively, appointing within thirty days Daniel C. McCallum (below) as director of the United States Military Railroads (USMRR).

Daniel C. McCallum (1815 – 1878)’

Photo Source: Wikicommons, Public Domain

In May of 1862, Abraham Lincoln “took formal possession of all railroads.” General McCallum recruited Herman Haupt (below), a “brilliant railroad engineer,” to assume duties as Military Director and Superintendent of the United States Military Railroad. Haupt was given the rank of Colonel and Lincoln gave him broad, albeit frequently challenged, powers.

Henry Haupt (1817 – 1905)

Military Director and Superintendent of the united States Military Railroad

In the next post, the action of the South.

You may also be interested in two of my previous posts on Civil War Railroads:

[i] Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 63.

[ii] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 165.

And so…The American Civil War

We ha ve arrived in “Studies in U.S. Military History” (see course information here) at the American Civil War. We’ll spend two weeks on this war, more than any other. Millett and Maslowski’s For the Common Defense splits the war into two periods: chapter six, 1861 – 1862 and chapter se

ve arrived in “Studies in U.S. Military History” (see course information here) at the American Civil War. We’ll spend two weeks on this war, more than any other. Millett and Maslowski’s For the Common Defense splits the war into two periods: chapter six, 1861 – 1862 and chapter se ven, 1863-1865. It is chock full of interesting statistics, enough to begin to fill a “page” on the blog where I can keep them handy. And so, yet another new page: the statistics.

ven, 1863-1865. It is chock full of interesting statistics, enough to begin to fill a “page” on the blog where I can keep them handy. And so, yet another new page: the statistics.

Next, a book I’ve already done a little reading in but am very much looking forward to, Edward Hagerman’s The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. This does not strike me as a fast read which is fine. I’m glad we can give it a solid two weeks.

And so a few statistics from Millett and Maslowski – always fascinating for this student of mathematics and engineering.

- 1861 White Male Population: North – 20 million; South – 6 million

- 800,000 immigrants arrived in the North, betwee 1861 adn 1865, including a high proportion of males liable for military service

- 20 – 25 percent of the Union Army was foreign-born

- 2 million men served in the Union Army

- 750,000 men fought in the Confederate Army which was a maximum strenght in late 1863 with 464,500

- Not all of these men on either side were “present for duty.” Out of the 464,500 Confederates, only 233,500 were “present for duty.”

- Taxation produced less than 5% of the Confederacy’s income. It produced 21% of Union government income.

- The Confederacy printed $1.5 billion in paper money, the Union $450 million in “greenbacks.”

- In 1860, the nothern states had 110,000 manufacturing establishments, the southern states, 18,000.

- During the year ending June 1, 1860, the states forming the Confederacy produced 36,790 tons of pig iron. The state of Pennsylvania alone produced 580,049 tons.

- The South contained 9,000 miles of railroad track to the North’s 30,000 miles.

- 100,000 Southern Unionists fought for the North with every Confederate state except South Carolina providing at least a battalion of white soldiers for the Union Army. Millett and Maslowski call these the “missing” Southern Army and “a crucial element in the ultimate Confederate defeat.

—–

Source: Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 163-167.

New Pages

As my studies progress, I’ve found need of several more pages on the blog. Those of you who roam around a bit will know that I’ve intentionally used the more static “page” feature of my blog template to accumulate information that I’m picking up from classes and research. To that end, I’ve added the following:

the philosophers / sociologists

I’ve discovered a group of people that aren’t pure historians and who have influenced thought in areas not specific to military history. You’ll only find Auguste Comte there so far but watch for more (interesting fellow – pictured here).

the terms

I’ve got a ton of new words / terminology coming my way and I need a spot to jot them down and eventually define them. I’d also like to be able to go back to them in one spot. It’s looking very highbrow-ish to me now that I’ve added words from today’s reading in Breisach. You, on the other hand, may look at the words and think I must have been sleeping in Freshman general ed classes. OK I knew some of these terms before today!

the railroads

It occurred to me when I did my two posts on the railroads and the American Civil War just how important the rails were to this – arguably – first modern war. Since I also have a page on the ships, I decided to begin collecting railroad information as well. For now it has links to the two railroad-specific post I made last month. More to come.

Kudos

Finally, I’ve add a kudos page which it’s possible is an act of shameful self-aggrandisement but I prefer to think of it as a karmic act of thanks to those folks who have taken the time to make a nice comment either on my blog or theirs. It’s my modest plug back to them and where possible, I provide a link to their site. Thanks to all for the encouragement. And if I missed anyone, I’ll hope to fill in the gaps shortly. Oh and by all means, if you’d prefer I take you name off of this page, do let me know.

Top photo: Auguste Comte. Public Domain. Source: Wikicommons.

Middle photo: Station at Hanover Junction, Pa., showing an engine and cars. In November 1863 Lincoln had to change trains at this point to dedicate the Gettysburg Battlefield. LOC: 111-B- 83.

Railroad Disaster – Gare Montparnasse

Dimitri Rotov over at Civil War Bookshelf has an interesting post on his blog here in response to my two posts on railroads during the civil war: “Were the North and South Equally Matched… On the Rails” here and “Railroad Generalship” here.

The dramatic photo on his post is that of a French train whose brakes failed at Gare Montparnasse is 1895. If you’re so inclined, you can read about that disaster on the Danger Ahead: Historic Railway Disasters website here.

You can see a larger version of the photo here.

Railroad Generalship

Following up on yesterday’s post “Were the North and South Evenly Matched….on the Rails,” which is essentially about railroad management during the American Civil War, I wanted to add some additional information and links that will allow further exploration if you are so inclined.

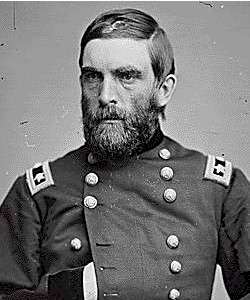

Arguably one of the greatest advantages the North had was in one Herman Haupt (1817 – 1905), a “brilliant railroad engineer” recruited in May of 1862 by General D. C. McCallum to assume duties as Military Director and Superintendent of the USMRR (United States Military Railroad). Haupt was given the rank of Colonel and Lincoln gave him broad, albeit frequently challenged, powers.[i]

Photo Above: A.J. Russell, photographer. Gen’l H. Haupt, ca. 1862 or 1863. LOT 9209, no. 21 LC-DIG-ppmsca-10341

Photo Below: Haupt’s torpedo for quickly wrecking wooden bridges CALL NUMBER: LOT 9209, no. 57 [P&P]

More than any other, Haupt should receive credit for shaping and building the USMRR. He developed general guidelines for using the railroads to provide supplies for the Army of the Potomac. During the fall of 1862, Haupt experimented with methods of destroying and repairing railroads and rail bri

dges. He developed a torpedo that could destroy a standard Howe Truss bridge, a U-shaped device that could quickly and easily destroy rails by twisting them, and new and faster ways to lay and repair track. Haupt and his engineers also experimented with new ways of bridge construction. As a result, preassembled bridge trestles were mass-produced and then transported in boxcars to areas where bridges needed repair or replacement. The rebuilding of bridges and track after Confederate raids was a never-ending process. Haupt also developed ambulance cars with surgeons and special equipment that increased the chances of survival for the wounded.[ii]

This quote is from the report summary of the archaeological dig of the Alexandria, Virginia United States Military Railroad Station, a fascinating look at one of the busiest sites of the war.

By the war’s end, there were 10,000 men in the United States Military Railroad service. Many were ex-slaves.

Photo Below: Military railroad operations in northern Virginia: men using levers for loosening rails. REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZ62-90111

Dr. Christopher R. Gabel (OSU and Command and General Staff College) has written an interesting piece titled “Railroad Generalship: Foundation of Civil War Strategy” available here.

A bibliographical listing of works dealing with railroads during the Civil War (and other American conflicts) is available here.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i, ii] THE BONTZ SITE (44AX103) THE UNITED STATES MILITARY RAILROAD STATION (44AX105) Report Summary by Shirley Scalley, accessed online 1/20/2008 at http://oha.alexandriava.gov/archaeology/pdfs/bontz8.pdf

Were the North and South Evenly Matched…on the Rails?

One of the questions that was much debated in class was whether the North and South were evenly matched in the American Civil War? To get the discussion rolling, our professor threw out the following…

In his interesting study of the American Civil War, Archer Jones argues in Civil War Command and Strategy: The Process of Victory and Defeat (1992), that despite its superior numbers, the Union advantage was greatly diminished by the extent of Southern territory, the intrinsic superiority of the defense over the offense, and the problems of supplying armies over long distances. Jones also states that Northern industrial dominance also proved almost useless in a war that depended less on complex weaponry and ammunition than on the man with the rifle. In Jones’ opinion, the two sides were, in fact, almost evenly matched.[i]

Our task was to take a stand on whether the North and South were evenly matched. I decided to focus on the very specific area of railroad transportation during the war. Part of my interest in this area comes from my association with friend and rail historian Peter A. Hansen, the editor of Railroad History and author of a number of articles for Trains Magazine. I was able to interview him on the topic and have included a good part of that in the post below. The photo below will be included in the upcoming issue of Railroad History which “is given over to a nearly-encyclopedic overview of every company that ever built steam locomotives in America.”[ii] The principal contributor is John H. White, Jr., former curator of transportation at the Smithsonian Institution.

Photo: New Jersey Locomotive & Machine-built 4-4-0 Fred Leach near Union Mills, Va., on August 1, 1863, the year after it was built. Its stack and tender have taken cannon shot, and the main rod is missing. It became Orange and Alexandria Warrenton after the American Civil War. Library of Congress: 111-B-185.

Charles Roland, in his book An American Illiad: The Story of the Civil War, provides a strong case for the American Civil War being considered the “first complete railroad war.” He asserted that the North was well ahead of the South in railroad resources entering into the war with 20,000 miles of rails in 1860 to the South’s 10,000. The railroads of the north were better “linked into systems of trunk lines that covered the entire region.”[iii] There were other things that made the North’s railroads superior. “First, it was dotted with locomotive factories, concentrated particularly in Massachusetts, Paterson, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. All of them remained beyond the reach of Rebel forces, so production was never disrupted. It was never disrupted for want of materials, either, since most of the iron ore and coal were also concentrated in the North.”[iv]

“In addition, the North’s railroads were almost all built to the standard track gauge of 4’ 8 ½”. That meant the cars could be interchanged from one line to another without the need for time-consuming unloading and reloading of passengers and freight. In the South, the rail network was pretty thin to begin with, and the multiplicity of track gauges hampered operations even more. That was particularly important considering that most of the war was fought on Southern soil. With the notable exception of one shining moment at the First Battle of Bull Run, the South was never consistently able to rush men and materiel to the front by rail. There were just too many obstacles to such smooth operation in most of Dixie.”[v]

Photo above: Station at Hanover Junction, Pa., showing an engine and cars. In November 1863 Lincoln had to change trains at this point to dedicate the Gettysburg Battlefield. LOC: 111-B- 83.

Photo below: The four-tiered, 780-foot-long railroad trestle bridge built by Federal engineers at Whiteside, Tenn., 1864. A guard camp is also shown. Photographed by George N. Barnard. LOC: 111-B-482.

“It’s a little-known fact, but track gauge was the first big standardization issue – in any industry. It seems incredible to us from our modern perspective, but many people were slow to grasp the need for standardization. It had never been needed in the days when every village had its own blacksmith or carpenter, whose products never needed to be used in conjunction with those of the smithy or carpenter in the next town.”[vi]

Photo above: Tredegar Iron Works. Artist: Alexander Gardener, Public Domain, Wikipedia Commons.

“The South didn’t have a single locomotive factory of any consequence during the Civil War. Several had made a start during the 1840s and 1850s but failed to survive into the War years – including Richmond’s famous Tredegar Iron Works (see the American Civil War Center’s site at Tredegar Iron Works here). While the firm itself survived until 1956, they produced locomotives only from 1851 to 1860. Even as the storm clouds were gathering, they decided in late 1860 that the locomotive business wasn’t profitable for them, and they retooled the shop for other uses.

“[vii]

Photo right (cropped): James Noble Sr. from www.civilwarartillery.com/manufacturers.htm.

“Aside from Tredegar, the only wartime Southern locomotive factory that’s even marginally worth mentioning was James Noble and Son of Rome, Georgia. They produced only a few locomotives after 1855 and their factory was destroyed by Sherman’s army in 1864. What this means, of course, is that Southern railroads became increasingly dysfunctional as their locomotives were destroyed, since they had no means of replacing them. It also meant that their remaining locomotives were often old, and/or held together by any means possible.”[viii]

McPherson substantiates this in his book, Battle Cry of Freedom. He indicates that of the 470 locomotives built in the U.S. in 1860; only 19 were built in the South.[ix] According to Hansen, “the production of 470 locomotives in a single year may seem like a large number. But it is less surprising in light of two things. First, railroad mileage in the U.S. had surpassed 30,000, and about 2/3 of that total had been built in the previous decade. Just like new highways today, there was comparatively little traffic on new lines in their first couple of years, but usage mushroomed when people and businesses began to change their previous transportation preferences, and when businesses began to locate along the new lines. When a line began to see more traffic, whether two or five or eight years after it was built, new locomotives were needed to handle it. An economist might say that the need for rolling stock lagged the actual construction by a few years.”[x]

“Another thing to consider is the poor utilization of assets in those days. Just as standardization was a new concept in the middle of the 19th century, so, too, was asset utilization. The latter concept is quite recent indeed, not being fully understood until just the past decade or so. [Note: Consider that Southwest Airlines ran circles around its competitors for years, chiefly because SWA insisted on having an entire fleet of identical planes, and on keeping them on the ground for only 30 minutes at each stop. The underlying rationale for both policies was better asset utilization. The older airlines are still struggling to apply those same lessons.] A steam engine is a highly labor-intensive beast. It requires constant attention from fireman and engineer alike in order to get maximum productivity while it’s working, and it spends about two hours in the shop for every hour it spends on the road. That time is absolutely necessary to the proper functioning of the machine, since grates need to be shaken, ashes need to be dumped, and moving parts need lubrication. (Tallow was a common valve lubricant in those days before petroleum engineering, and applications had to be repeated frequently.) About once a month, the steam engine’s fire was dumped altogether so the tubes and flues could be inspected. The process of cooling an engine down, inspecting it, and firing it back up typically took 24-48 hours, so there’s a big chunk of unproductive time right there. So the bottom line is that they needed a lot of locomotives in those days!”[xi]

Brilliant Uses of Railroads

The South did have some success with the use of trains for troop transfer. Johnston’s use of the Manassas Gap Railroad to move his troops to Manassas Junction to reinforce Beauregard was brilliant and no doubt influenced the outcome of that engagement which so demoralized the North. Roland also reviews Bragg’s “almost incredible strategic use of the railroads” against Buell as the latter approached Chattanooga. “The Confederates half-circled the Union army by moving 30,000 from Tupelo, Mississippi, roundabout by way of Mobile and Atlanta to Chattanooga, a movement of some 776 miles.”[xii] Hansen felt that, “while it was true that Bragg’s campaign was a remarkable success in the face of daunting logistics, this was the exception that proves the rule.” The mere fact that he had to detour 776 miles in order to go 300 speaks to the paucity of railroads in the South. And even in his 776-mile detour, he had to port his troops on foot east of Montgomery, where the railroad ended, before he could load them on trains again near Columbus, Georgia. So yes, the railroads helped him win, but I submit that it was his audacity, combined with Buell’s dithering, that gave him the ability to make the best of a questionable asset.”[xiii]

Hansen added, that “it is worth noting that railroads were the whole reason Chattanooga had such strategic significance. The principal line from Richmond to Atlanta, and the line from Memphis to the east, converged there. Without Chattanooga, the South’s ability to move men and materiel by rail in their own territory was all but gone.”[xiv]

Thomas Ziek, Jr. came to the same general conclusion in his Master’s Thesis, “The Effects of Southern Railroads on Interior Lines during the Civil War.” He tried to determine whether or not the South enjoyed the advantage of interior lines and concluded that they did not.

The use of railroads during this conflict placed an enormous physical strain upon the limited industrial resources of the Confederacy, and a great strain upon the intellectual agility of the Confederate High Command. Based upon the evidence studied, and the time-space comparisons of both Northern and Southern railway operations, several conclusions can be drawn: the South entered the war with a rail system that was unable to meet the demands of modern war; the Confederate leadership understood the importance of the railroad and its importance to strategic operations early in the war, but were unwilling to adopt a course of action that best utilized their scarce assets; Union control, maintenance, and organization of its railway assets ensured that it would be able to move large numbers of troops at the strategic level efficiently from early 1863 to the end of the war. Based on these conclusions, the Confederacy lost the ability to shift troops on the strategic level more rapidly than the Union by 1863. This was a result of its physically weakened railroad system and military setbacks which caused Southern railroads to move forces over longer distances.[xv]

My conclusion, for this area of focus, is that the North and South were NOT equally matched either in their physical rail assets nor in their management of those assets. While the South had some moments of brilliance in their use of railroads, they simply did not have the infrastructure to maintain, let alone expand, the railroads of their region to their greatest advantage.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i] White, Charles, AMU CW500.

[ii, iv, v, vi, vii, viii, x, xi, xiii, xiv] Hansen, Peter A., Personal interview. Sept. 9, 2007

[iii, xii] Roland, Charles P. An American Iliad: The Story of the Civil War

[ix] McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom

[xv] Ziek, Thomas G., Jr., “The Effects of Southern Railroads on Interior Lines During the Civil War.” A Master’s Thesis.