Archive for July 2009

On Geography Lessons and Civil War Cartography

–

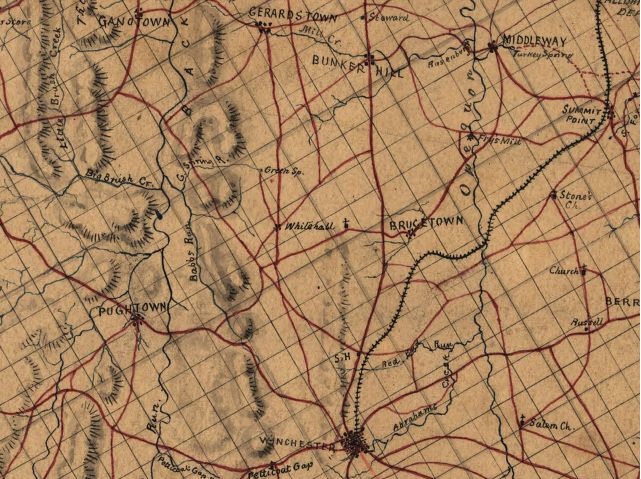

The highlight of the first five chapters of Two Great Rebel Armies by Richard M. McMurray was hands down the lesson on geography. This is, I fear, an area that receives too little emphasis in our study of the war. Particularly interesting was the reference to the Shenandoah Valley (Valley of Virginia) and the advantages and disadvantages it presented to those who chose to maneuver in it. It helps me to actually “see” a map of the area and I found a collection that you might find helpful if you’ve not already discovered it. It is the Hotchkiss Collection on the Library of Congress site here. The collection consists of 341 sketchbooks, manuscripts, and annotated printed maps, the originals of which reside in the Library of Congress’ Geography and Map Division. It also provides two essays including a biographical essay about Hotchkiss. Not to be missed is the Map of the Shenandoah Valley which was considered a masterpiece.

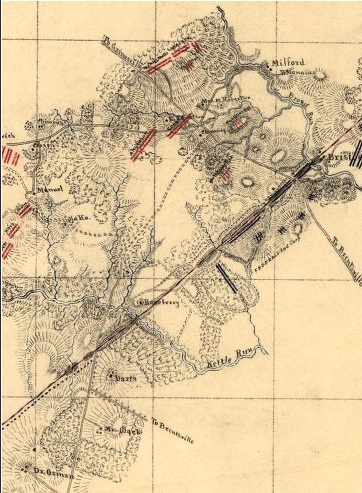

Sketch of the Battle of Bristoe, Wednesday, Oct. 14, 1863 / by Jed. Hotchkiss, Capt. & Top. Engr., 2nd Corps, A.N.Va. (Library of Congress)

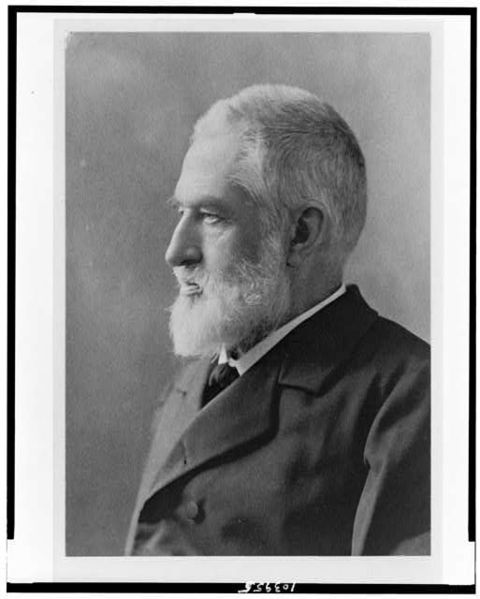

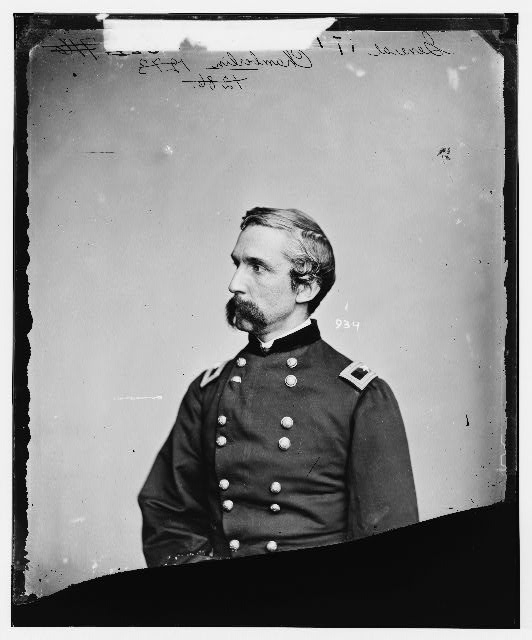

Major Jedediah Hotchkiss (1828-1899) was considered the cartographer of the Army of Northern Virginia. He was a topographic engineer in the Confederate Army. Most of the works in the collection are of the Shenandoah Valley and certainly some would have been used by Lee and his commanders.

Jedediah Hotchkiss

The letters of Jedediah Hotchkiss are available on the University of Virginia’s excellent The Valley of the Shadow digital history project here. This exceptional collection is well worth the read and covers the major’s war experiences from 1861 – 1864 as conveyed to his family.

Military History Word of the Day: “Ambuscade”

–

am⋅bus⋅cade

[am-buh-skeyd] noun, verb, -cad⋅ed,

–noun

1. an ambush

–verb (used without object)

2. to lie in ambush.

–verb (used with object)

Jeb Stuart

3. to attack from a concealed position; ambush.

1575–85; < MF embuscade, alter. (under influence of OF embuschier) of MF emboscade < OIt imboscata, fem. ptp. of imboscare, v. deriv. with in- of bosco wood, forest < Gmc *bosk- bush

Related forms: am⋅bus⋅cad⋅er, noun [1]

—-

As used by Joseph L. Harsh in Taken at the Flood…

On this occasion, Jeb Stuart justified his reputation for alert reconnaissance. Almost instantaneously he perceived and reported to Lee the enemy’s rapid withdrawal. He also ordered Hampton to pursue and harass the Federal column retiring from Flint Hill toward the Chain Bridge. Into the hours of darkness, Hampton closely pressed the Federal tail under Sedgwick, lobbing shells into the panicky main body until the heavy casualties suffered by the 1st North Carolina Cavalry in an “ambuscade” laid by the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry bought breathing space for the retreating Federals. Meanwhile, in the center of the line, where Stuart had only Fitz Lee’s tired troopers, the Confederate horsemen pressed more gently and permitted Hooker to withdraw through the county seat virtually unscathed. Heros von Borcke, Stuart’s Prussian chief of staff (see his memoir online here), planted the Confederate colors on the courthouse green, while deliriously happy Southern sympathizers mobbed the troopers, and damsels showered Stuart with kisses. Jeb even found time to visit his friend and “spy” Antonia Ford. [2]

—–

[1] ambuscade. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/ambuscade (accessed: July 25, 2009).

[2] Joseph L. Harsh, Taken at the Flood : Robert E. Lee and Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862 / [book on-line] (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999, accessed 25 July 2009), 19; available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=102364729; Internet.

More Debate on The State of Jones and Interview with John Stauffer

–

A quick break from the books to tip the hat to Elektra Tig for Tweet on John Stauffer interview here on the Omnivoracious blog about his book, The State of Jones.

The book continues to generate debate.

The Wall Street Journal posted a chapter in their books section here and Michael B. Ballard’s review of the book appears in the WSJ here. Authors Sally Jenkins and John Stauffer provide a response/rebuttal to that review on July 17th in an article titled “The State of Jones Was Real, and Ahead of Its Time” available here. The debate continues to be fascinating.

OK back to Taken at the Flood.

Up this week: Taken at the Flood

I’m thrilled to be finally reading Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Clearly I must obtain copies of the other books in this series.

The State of Jones Debate

There is a fascinating debate afoot on the new book The State of Jones I mentioned in a post on June 23rd here. Authors John Stauffer and Sally Jenkins respond to the three part review by Vicki Bynum. I suggest that interested readers begin with Dr. Bynum’s review (Part III here) and then make your way over to Kevin Levin’s blog post where the majority of the debate is captured here.

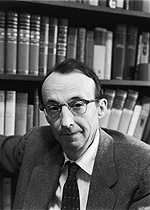

Civil War Historian Kenneth M. Stampp Dies, 96

The folks at the Berkeley’s public affairs office confirmed for me today that Kenneth M. Stampp died. His book The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South (1956) is required reading in my program and rightly so. The view into slavery was groundbreaking.

A full obituary will be posted shortly on Berkeley’s news site.

Condolences to his family.

(http://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2009/07/13_stampp.shtml)

Book Review: Lincoln and His Generals

T. HARRY WILLIAMS. Lincoln and His Generals. New York: Random House, 1952. Pp. viii, 363, $2.40.

T. HARRY WILLIAMS. Lincoln and His Generals. New York: Random House, 1952. Pp. viii, 363, $2.40.

T. Harry Williams

Over half a century ago, T. Harry Williams wrote an exceptional work with as major theme that the performance of President Abraham Lincoln as commander in chief during the American Civil War positioning him as the true director of the war efforts of Northern armies and the progenitor of the country’s first modern command system. He shows Lincoln to be an able student of military strategy who ramped up quickly, grasped the end game and generally how to reach it, but struggled to find the right executioner of those plans. That he was even more skilled as a politician meant that he functioned superbly as leader in both political and military spheres throughout the conflict.

This is a work about the challenges of leadership set against what Williams calls the first of the “modern total wars.” (3) Williams chronicles the war from Lincoln’s perspective presenting the strengths and, more notably, the many foibles of the men who served the North in senior military positions. Their relative caliber appears to have been directly correlated to the attention Lincoln had to give them. More attention from and scrutiny by Lincoln was thus not a mark of achievement. Williams’ work reflects that relative attention. For example, he begins his discussion of McClellan in Chapter 2 and does not finish with him until Chapter 8 at which point Lincoln finally dismisses McClellan in disgust. (179) Williams takes his readers through the agonizing months Lincoln spent attempting to manage McClellan and his paranoia regarding enemy troop strength and inability to execute when it would put his men in harm’s way or there was the potential to fail. Grant, by contrast to McClellan, received some but not extensive coverage by Williams reflecting Lincoln’s own confidence that Grant could carry forward Lincoln’s strategic aims effectively. Williams concludes that in the waning months of 1864, Lincoln had sufficient trust in Grant to intervene little in the war’s management. That is not to say that Lincoln shrugged off any responsibility in setting strategic direction or in monitoring closely “and sometimes anxiously” the conduct of the war. (336) He was quick to reset direction when required.

Williams’ organization of the book is driven largely by the order of his encounters with senior military leaders. He begins with the infamous but corpulent and declining General Winfield Scott. We are given images of Lincoln chatting by the fire in Scott’s drawing room about daily reports and strategic options. Lincoln begins to reveal his own nascent military strategies and to measure those proposed by the militarist Scott against civilian and political realities. Lincoln also demonstrates an important resolve to make and stand by decisions even if they go against those of senior military advisors. Williams provides illustration of this by pointing to Lincoln’s grasping of the strategic golden nugget within Scott’s Anaconda Plan of control of the Mississippi but Lincoln’s rejection of its execution because it risked a drawn out and uncertain resolution.

Regular army man Irvin McDowell is then tagged by Lincoln to take command of the swelling number of troops in and around Washington, a number that by the summer of 1861 exceeded 30,000 men. Lincoln pushes McDowell, of course, into an offensive movement at Manassas to disastrous results. While the mark against McDowell’s mediocre reputation is severe, Williams allows us to see that Lincoln is willing to bear some of the blame.

The scene is thus set for the summoning of McClellan to Washington. This begins Lincoln’s relationship with “the problem child of the Civil War.” (25) Williams chronicles the early months of McClellan’s experiences in the East, his messianic complex, disrespect for Lincoln and others with whom he had to deal, and the efforts that Lincoln had to make to manage a man who held such promise but failed to deliver. It is clear that Lincoln, to this credit, attempted many different techniques in his efforts to supervise McClellan.

John C. Fremont, McClellan’s peer in the Western Department and a political appointment made by Lincoln himself, proves disastrous in his mismanagement of Missouri and a bitter disappointment. Williams captures well the odd quirks of both Fremont and the Blair family, his patrons, and the lengths to which Lincoln had to go to remove him.

Halleck is portrayed as only marginally effective and jealous enough of Grant’s successes in the field to take credit for them. (61) His self-directed shift to subordinate role as coordinator and communicator between Lincoln and his staff is fascinating.

Other commanders are mentioned primarily for their lack-luster performances including Rosecrans, Buell, Thomas, Banks, and Butler to name a few. Williams’ provides an excellent summary of each man including physical characteristics, approach to command, reputation, and personality traits. He often reveals the quirks or failings that made them less than acceptable as senior command candidates. For example, he describes Benjamin F. Butler as “ingenious, resourceful, and colorful, but …no field general.” (188) Williams’ description of Rosecrans reveals a well researched sum of the man from his “intensified Roman nose” to his “good strategic sense and aggressive instincts.” (186-187) But he is thorough enough to point to Rosecrans weaknesses including a lack of “balance and poise that a great commander should have” which revealed a man unable to “control himself and the situation.” (187)

Clearly apparent in this history is that Lincoln, while climbing a steep learning curve, became an astute war strategist. In fact, Williams contends that the notion of “total war” as a means of destroying the Confederate Army was identified earliest and most enthusiastically as a strategic plank by Lincoln who “saw the big picture” better than most of his commanders and staff. (7) He further asserts that no one in the military leadership of either side had the experience to wage war at the scale that would be America’s Civil War. Both sides shared an equal innocence of the knowledge war making. (4) That said, Lincoln’s performance when viewed against that of Davis is all the more impressive.

Williams points out that Lincoln exhibited many good qualities as a leader. By example, he was not quick to claim credit for the successes of Sherman, even though he would have been justified to do so given the strategic direction he provided. Rather, Lincoln showered praise on men whose efforts were successful. He seemed to simply want vigilance and self-reliance from his commanders, both qualities he saw in Grant. (315)

Williams’ use of primary sources is impressive and adds credibility to his conclusions. Many citations were from actual correspondence or official records of exchanges between Lincoln and his team or Halleck and the field commanders. This depth of research adds much to the work.

At the time of publication, this book was the only one to fully examine Lincoln’s performance as commander in chief and stood as such for many years. Interestingly, in 2009, historian James McPherson visited the same topic and drew much from Williams’ foundation in his work, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief. While good, I find it no better and in many ways a rehashing of Williams’ work, one that continues to stand on strong scholarship and goes far toward explaining Lincoln’s brilliance as both politician and military strategist.

Audio Recordings of CUNY Roundtable on Writing History

For fellow graduate history students with a thesis or dissertation ahead or in progress, or for anyone who wrestles with the writing of history, I hope you’ll find as interesting as I did this audio capture of a roundtable of history professors sharing their perspectives on the craft. Also helpful is the Q & A with students. The speakers are listed below along with the links to their individual talks.

This is also available on the Resources page of the Ph.D. in History Program, City University of New York (CUNY) here.

Introduction (David Nasaw)

Dagmar Herzog

Thomas Kessner

David Nasaw

Steven Remy

Martin Woessner

Comments and Questions

Staff Ride Guide – Battle of Antietam

Informative read about the Battle of Antietam prepared as a “Staff Ride Guide” by Ted Ballard, CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY, UNITED STATES ARMY. This assisted, among other things, with my understanding of artillery and particularly how units were organized who supported the guns. Interesting factoids from page 83 -84 (note this entire book is available online by clicking on the book image above):

“The artillery of both armies was generally organized into batteries of four or six guns. Regulations prescribed a captain as battery commander, while lieutenants commanded two-gun “sections.” Each gun made up a platoon, under a sergeant (“chief of the piece”) with eight crewmen and six drivers.

For transport, each gun was attached to a two-wheeled cart, known as a limber and drawn by a six-horse team. The limber chest carried thirty to fifty rounds of ammunition, depending on the size of guns in the battery. In addition to the limbers, each gun had at least one caisson, also drawn by a six-horse team. The caisson carried additional ammunition in two chests, as well as a spare wheel and tools. A horse-drawn forge and a battery wagon with tools accompanied each battery. A battery at full regulation strength included all officers, noncommissioned officers, buglers, drivers, cannoneers, and other specialized functions and might exceed 100 officers and men. With spare horses included, a typical six-gun battery might have 100-150 horses.

A battery could unlimber and fire an initial volley in about one minute, and each gun could continue firing two aimed shots a minute. A battery could “limber up” in about one minute as well. The battery practiced “direct fire”: the target was in view of the gun. The prescribed distance between guns was fourteen yards from hub to hub. Therefore, a six-gun battery would represent a front of about 100 yards. Depth of the battery position from the gun muzzle, passing the limber, to the rear of the caisson was prescribed as forty-seven yards. In practice, these measurements might be altered by terrain.”

Gettysburg: The Film, The Books, The Battle

Little Round Top Union Breastworks (Source: The National Archives) Brady

Each July we bring out the film Gettysburg and watch it in a couple of sittings. (My husband can’t wait for the four plus hour epic to come out in Blu-ray.)

I’ll be the first to admit that it’s more than a bit hokey here and there but the scene of the defense of Little Round Top by the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment is always a highlight.

My current reading for class discusses the legacy of bayonet charges from the Mexican War and the debate over the frequency of their use during the American Civil War still goes on. Undebatable is the inspired use of a downhill bayonet charge by Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and its standing on the list of well-known actions at Gettysburg.

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

I’ve been enjoying the perspectives of several ACW bloggers on their top ten books on Gettysburg which Brett over a TOCWOC has nicely organized for us here.

Check them out. Very much worth perusing.

American Civil War Artillery Demonstration, Antietam National Park

Excellent demonstration of how a gun crew handled artillery during the American Civil War can be seen below.

Antietam Artillery Demonstration

Ranger Mannie Gentile has become an excellent film maker. His blog, My year of living Rangerously, remains one of my favorites.

Solving a Civil War Photograph Mystery

Grant at Center Point (Careful!) LC-DIG-ppmsca-15886 (digital file from original photograph) , LC-USZ62-21992 (b&w film copy neg.)

The Library of Congress has a new entry in their always fascinating Civil War Photographs section. They challenge the authenticity of the photo above which the owner of the copyright, Levin C. Handy (1855-1932) and nephew of Mathew Brady, claims to be General Grant at Center Point, Virginia. They step the reader through their discovery process which reveals …. well I won’t spoil it for you. Find out for yourself how this photo was created here.

On Military Preparedness and Cartography during the American Civil War

County Map Of Virginia, and North Carolina. 23. Entered ... 1860, by S. Augustus Mitchell, Jr. ... Pennsylvania, Source:David Rumsey Map Collection http://www.davidrumsey.com

From class reading several weeks ago, I thought I would share a fascinating quote from T. Harry Williams and his 1952 work Lincoln and His Generals discussing the military preparedness of both sides to wage the war between the states.

“All of them were unready for war in 1861, and in that year and even later were not able to furnish field commanders with the technical information or advice or supplies which they were suddenly called on to provide. One of the most ironic examples of American military unreadiness was the spectacle of Northern – and Southern – generals fighting in their own country and not knowing where they were going or how to get there. Before the war the government had collected no topographical information about neighboring countries or even the United States, except for the West. No accurate maps existed. General Henry W. Halleck was running a campaign in the western theater in 1862 with maps he got from a book store.”

By the way, I highly recommend the David Rumsey Map Collection site available here. Outstanding collection of maps and the user interface is superb!