Posts Tagged ‘Civil War’

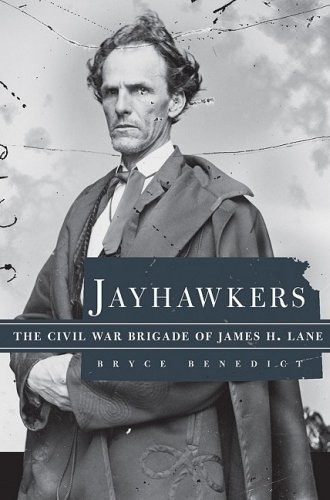

Jayhawkers: The Civil War Brigade of James Henry Lane

ISBN: 978-0-8061-3999-9

Cloth

352 pages

12 b&w illus., 1 map

Published: 2009-04-30

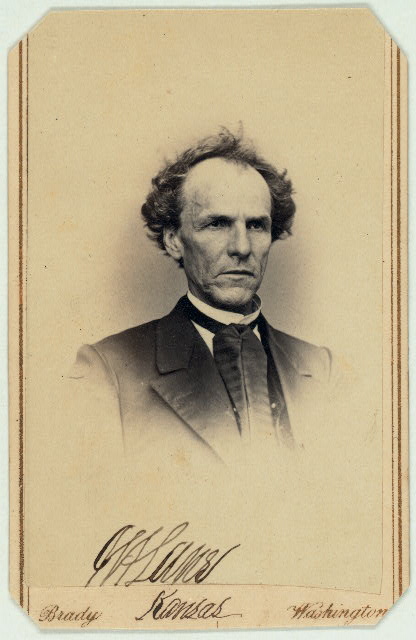

Carte d' visite of James Henry Lane, 1814-1866 Photographer: Brady National Photographic Art Gallery (Washington, D.C.) Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-MSS-44297-33-037 (b&w negative)

The good folks at the University of Oklahoma Press sent me a review copy yesterday of Bryce Benedict’s Jayhawkers: The Civil War Brigade of James Henry Lane. In my usual fashion, I’m posting a few comments prior to a thorough reading.

I live on the borders of Missouri and Kansas so confess some considerable fascination with both Jim Lane and the evolution of war in the towns and farmlands of this part of the Western theater. Lane, a Kansas senator and strong advocate of Lincoln, was a player. Benedict identifies Lincoln himself as having given Lane authority “to raise and command two volunteer regiments.” Lane used them to harass Missourians with violence, theft, and destruction of property in a manner foreshadowing that of Sherman. Benedict posits that Lane thus embraced the notion of “total war” as a means of disabling the enemy’s war machine before it became more widely adopted as a strategy of the Union.

The photo of Lane on the cover (above) was a brilliant choice. After perusing the Library of Congress and finding his carte d’visite (left), it becomes clear that the look of the man fit his personality. In the words of Milton W. Reynolds, Lane was “weird, mysterious, partially insane, partially inspired, and poetic.” He described him as having lived a “…wayward, fitful life of passion and strife, of storm and sunshine a mysterious existence that now dwelt on the mountain-tops of expectation and the very summit of highest realization, and anon in the valley of despondency and deepest gloom.” [1] Lane committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth with a pistol in 1866.

Author Bryce Benedict has produced a well researched work with notes for each chapter and three appendices including considerable information about fate of the casualties of Lane’s brigade, most of whom died from disease.

—–

For further reading, check out these books digitized for online reading at the Library of Congress.

[1] Connelley, William Elsey, (1855-1930) James Henry Lane, the “Grim chieftain” of Kansas (Topeka: Crane, 1899). The Library of Congress Digitized Book. LOC Call number: 9594581, Digitizing sponsor: Sloan Foundation

California Hundred Battle Guidon

A friend just sent this. Very cool.

A battle guidon carried by members of the California Hundred – cavalry volunteers who served in the Massachusetts 2nd. The only surviving California flag from any Civil War engagement, these colors

witnessed action in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864.

See more on this flag at the Fort Tejon Historical Society here.

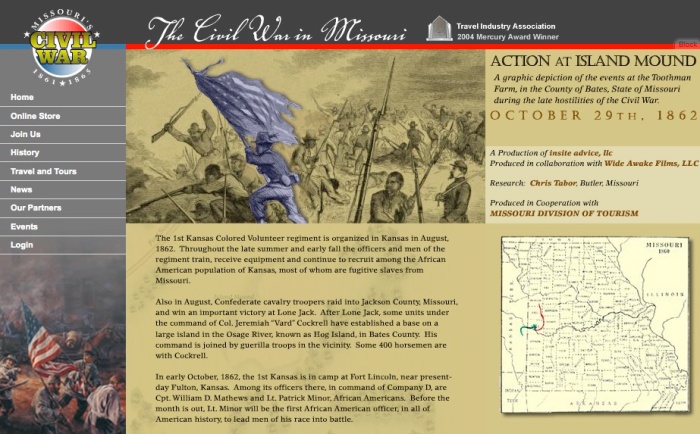

The Civil War in Missouri – Top Notch Website

There are some terrific sites out there about the American Civil War. The Civil War in Missouri is one of the best.

Among my favorite features in the historical section is a collection of “Animated Battles” that combine audio, film of enactors, and battle maps with action depicted by moving units, fires that blaze, and the sounds of hoof beats and rifle fire. Very cool. This is a great site for students.

Technology in U.S. Military History – 1

My current course on Studies in U. S. Military History (see courses page here) is drawing to a close. We have been examining the last of Millett and Maslowski’s major themes which is that “the United States has used increasingly sophisticated technology to overcome logistical limitations and to match enemy numbers with firepower.” [i] I find this supportable in the sense that it has been possible to see a steady progression of technological prowess over time. Nowhere, arguably, have technological advancements been felt more than in the arena of weaponry.

Professor of history Alex Roland (Duke University) posits that “before the twentieth century, most soldiers and sailors ended their careers armed as they were at the beginning. New weapons were introduced slowly, if at all, and most professionals resisted the uncertainties new arms introduced.” But, Roland asserts, “by the second half of the twentieth century, this traditional suspicion of new weapons had changed to a reckless enthusiasm.” The phenomena of obsolescence on introduction entered the national psyche in that, by the time many “weapons entered service, their successors were being planned. This was especially true in large-scale weapons systems such as ships and aircraft. It even found its way into thinking about less complex military technologies, such as radios and computers.” [ii]

More in Part 2. Note I provide a link below to Professor Roland’s excellent article titled “Technology and War” which can be read online.

[i] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, xiii.

[ii] Alex Roland, “Technology and War,” http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/AD_Issues/amdipl_4/roland2.html Accessed 13 July 2008.

“Texas Jack” Omohundro Round Up

I’m vacationing this week in Forth Worth, Texas attending the “Texas Jack Round Up,” the bi-annual gathering of the “Texas Jack” Association (see website here). John B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro was enormously famous in his era. The best friend of William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, he was a famous western scout. And, he’s family, that is to say I married into the extended family.

John B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro

Source: http://www.Texasjack.org

The following is a quick snapshot of Jack’s Civil War experience.

When the war between the states broke out, Jack’s older brother Orville (pictured with Jack below) joined the Confederate army as a lieutenant under the command of Col. J.E.B Stuart. Jack, then 14, immediately volunteered his services, and was, to his great disappointment, denied because of his age. After several attempts, he was finally accepted into the army when he was l6, and was assigned to his brother’s regiment.

John B. (left) and Orville Omohundro

Source: http://texasjack.org

Jack immediately gained renown as a scout of ability and bravery, working directly under Col. Stuart (pictured below), and was soon to be widely known as the “Boy Scout of the Confederacy”. Many times, he would act as a spy, moving among the Union troops as a chicken peddler or some other kind of tradesman, obtaining information about the enemy. Little was he to know that within the next 10 years, his best friends and saddle-mates would be former Union soldiers.

Colonel J.E.B. Stuart, CSA

Sources: Wikicommons

Civil War Railroad Page Updated

By way of housekeeping, I’ve updated the Popular Series Posts page on the right nav bar titled Civil War Railroads here with the latest series of posts titled “Stewards of Civil War Railroads.”

Above: United States Military Railroad 4-4-0 locomotive W.H. Whiton (built by William Mason in 1862) in January 1865 with Abraham Lincoln’s presidential car, which later was used as his funeral car.

Source: Wikicommons

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part III

This post completes the series, Stewards of Civil War Railroads. Read Part I here and Part II here.

Above: Group of the Construction Corps U.S. Mil. R. Rds., with working tools, etc., Chattanooga, Tennessee

Courtesy of Library of Congress: LC-USZ62-62364

Millett and Maslowski posit that President Abraham Lincoln did not have Jefferson Davis’ sensitivity about government interference with railroads. The evidence supports the point and also suggests that Davis’ hands-off approach expanded to other areas under his purview including signals and communications. Whether he was afflicted with chronic indecisiveness or was bowing to the perceived whims of a public unreceptive to “big government” is open for discussion but as in many things, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Regardless, it is clear that rational military considerations were not the sole concern in shaping the South’s military policies and programs. Had they been so, military needs would have received higher priority and the events of the war may have flowed differently.

Above: Lincoln and McClellan

The impact of the decision making processes in the Lincoln and Davis administrations and the respective Congresses as regards those issues impacting the military is indeed a fascinating one and worthy of continued analysis and review. Clearly the social, economic, and political nuances of the North versus the South had much to do with the directions taken within each section. But one is left to wonder whether the leadership qualities of Lincoln and Davis, including the ability to be decisive, allowed the North to more frequently follow a path guided by rational military reason.

Above: The engine “Firefly” on a trestle of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part I Lincoln

The decisions made by leaders of the North and South regarding the dispensations of their respective railroads, could arguably be some of the most impactful of the war. Armies on both sides considered railroads critical. But Lincoln and Davis approached the control and stewardship of these vital resources differently. The resulting policies did not equally reflect rational military consideration.

Above: United States Military Railroad 4-4-0 locomotive W.H. Whiton (built by William Mason in 1862) in January 1865 with Abraham Lincoln’s presidential car, which later was used as his funeral car.

Source: Wikicommons

The need for oversight of the rails came early in the war. Edward Hagerman highlights Federal Quartermaster General Meigs’ complaints in the opening months of the war over the problems of coordination that arose “from civilian control of the railroads.” [i] In January of 1862, Congress gave Lincoln the authority he needed “to take control whenever public safety warranted it.” [ii] Lincoln moved decisively, appointing within thirty days Daniel C. McCallum (below) as director of the United States Military Railroads (USMRR).

Daniel C. McCallum (1815 – 1878)’

Photo Source: Wikicommons, Public Domain

In May of 1862, Abraham Lincoln “took formal possession of all railroads.” General McCallum recruited Herman Haupt (below), a “brilliant railroad engineer,” to assume duties as Military Director and Superintendent of the United States Military Railroad. Haupt was given the rank of Colonel and Lincoln gave him broad, albeit frequently challenged, powers.

Henry Haupt (1817 – 1905)

Military Director and Superintendent of the united States Military Railroad

In the next post, the action of the South.

You may also be interested in two of my previous posts on Civil War Railroads:

[i] Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 63.

[ii] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 165.

On the Civil War’s Last Veterans, Wives, and Stats

While in search of documentation for Civil War statistics, I discover the Fact Sheet: American Wars published in November 0f 2007 by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. It provides the following:

It lists the last Union veteran as Albert Woolson (right) who died August 2 1956 at age 109. He was a member of Company C of the First Minnesota Heavy Artillery Regiment but never saw action. A brief biography is available here.

The last Confederate Veteran, John Salling, died March 16, 1958, at age 112. Some references, including one available here, suggests that he may have been an imposter.

And the last Union widow, Gertrude Janeway, died January 17, 2003, age 93. Mrs. Janeway death was covered in the January 21, 2003 issue of New York Times here. In brief, she was married to Union veteran John Janeway at age 16. He was 81. They made their home in a three room log cabin in Blaine, Tennessee. He died there at age 91 in 1937. She died in the same home. Mr. Janeway fought for the 11th Illinois Calvary under the name January. A photo of Mr. and Mrs. Janeway shortly after their wedding and of Mrs. Janeway in 1998 available here.

The last Confederate widow was Mrs. Alberta S. (Stewart) Martin who died in May 31, 2004. A site dedicated to Mrs. Martin including photos is available here. She was married to veteran Willaim Jasper Martin when she was 21 and he was 81.

A transcript of a 1998 interview with Mrs. Martin is available on radiodiaries.org here. Host Robert Siegel also interviews Daisy (Graham) Anderson who was, at the time, also one of the last know Union widows. Mrs. Anderson was married in 1922 at age 21 to Robert Anderson, then age 79, who was an escaped slave who joined the Union Army and served in the 125th Colored Infantry near the war’s end and in the Indian campaigns. He was a successful homesteader in Nebraska. Their story is available in the New York Times article about her death here. A article about Mr. Anderson’s fascinating life, titled “The Odyssey of an Ex-Slave: Robert Ball Anderson’s Pursuit of the American Dream,” by Darold D. Waxm is available through JSTOR here.

Civil War (1861-1865)

Total U.S. Servicemembers (Union)…………..2,213,363

Battle Deaths (Union)………………………………140,414

Other Deaths (In Theater) (Union)………………..224,097

Non-mortal Woundings (Union)…………………..281,881

Total Servicemembers (Conf.) (note 2) ………..1,050,000

Battle Deaths (Confederate) (note 3) ………………74,524

Other Deaths (In Theater) (Confed.) (note 3, 4)……59,297

Non-mortal Woundings (Confed.) ……………..Unknown

2. Exact number is unknown. Posted figure is median of estimated

range from 600,000 – 1,500,000.

3. Death figures are based on incomplete returns.

4. Does not include 26,000 to 31,000 who died in Union prisons.

Mahan’s Elementary Treatise

WOW! I am absolutely engrossed in Edward Hagerman’s The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. So much to say about Dennis Mahan (right) who I wrote about briefly here in my series on Jomini on the Nature of War (Part VII – Jomini’s Impact on Civil War Leadership). The National Park Service has a good bio on Mahan here.

WOW! I am absolutely engrossed in Edward Hagerman’s The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. So much to say about Dennis Mahan (right) who I wrote about briefly here in my series on Jomini on the Nature of War (Part VII – Jomini’s Impact on Civil War Leadership). The National Park Service has a good bio on Mahan here.

I was very pleased to find online Mahan’s Elementary Treatise on Advance-Guard, Out-Post, and Detachment Service of Troops (1847) which Hagerman references in detail. This text was developed by Mahan for West Point and is considered the first tactics and strategy text created for the United States. I’ll add this to my primary sources links on Wig-Wags.

I can tell already that I’ll have many terms to add to the terms page. More to come of the French connection.

And so…The American Civil War

We ha ve arrived in “Studies in U.S. Military History” (see course information here) at the American Civil War. We’ll spend two weeks on this war, more than any other. Millett and Maslowski’s For the Common Defense splits the war into two periods: chapter six, 1861 – 1862 and chapter se

ve arrived in “Studies in U.S. Military History” (see course information here) at the American Civil War. We’ll spend two weeks on this war, more than any other. Millett and Maslowski’s For the Common Defense splits the war into two periods: chapter six, 1861 – 1862 and chapter se ven, 1863-1865. It is chock full of interesting statistics, enough to begin to fill a “page” on the blog where I can keep them handy. And so, yet another new page: the statistics.

ven, 1863-1865. It is chock full of interesting statistics, enough to begin to fill a “page” on the blog where I can keep them handy. And so, yet another new page: the statistics.

Next, a book I’ve already done a little reading in but am very much looking forward to, Edward Hagerman’s The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. This does not strike me as a fast read which is fine. I’m glad we can give it a solid two weeks.

And so a few statistics from Millett and Maslowski – always fascinating for this student of mathematics and engineering.

- 1861 White Male Population: North – 20 million; South – 6 million

- 800,000 immigrants arrived in the North, betwee 1861 adn 1865, including a high proportion of males liable for military service

- 20 – 25 percent of the Union Army was foreign-born

- 2 million men served in the Union Army

- 750,000 men fought in the Confederate Army which was a maximum strenght in late 1863 with 464,500

- Not all of these men on either side were “present for duty.” Out of the 464,500 Confederates, only 233,500 were “present for duty.”

- Taxation produced less than 5% of the Confederacy’s income. It produced 21% of Union government income.

- The Confederacy printed $1.5 billion in paper money, the Union $450 million in “greenbacks.”

- In 1860, the nothern states had 110,000 manufacturing establishments, the southern states, 18,000.

- During the year ending June 1, 1860, the states forming the Confederacy produced 36,790 tons of pig iron. The state of Pennsylvania alone produced 580,049 tons.

- The South contained 9,000 miles of railroad track to the North’s 30,000 miles.

- 100,000 Southern Unionists fought for the North with every Confederate state except South Carolina providing at least a battalion of white soldiers for the Union Army. Millett and Maslowski call these the “missing” Southern Army and “a crucial element in the ultimate Confederate defeat.

—–

Source: Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 163-167.

Jomini on the Nature of War – Part II – The Burgeoning Military Theorist

This post continues from Part I here. Please note links in blue lead to additional information on those topics.

Antoine-Henri Jomini (below right) was born on March 6, 1779 in the small town of Payerne (Payerne church pictured right) in western Switzerland. His family was an old and influential one; his father Benjamin active in local politics. Jomini grew up with the French Revolution and the sight of French soldiers was something he was familiar with even as a boy. He was a teenager working in banking in Paris when the Swiss Revolution of 1798 broke out, largely instigated by the French at the proding of exiled Swiss radicals. Jomini’s father joined the revolutionary cause and served in various political roles in the Helvetian Republic. Antoine-Henri caught the fever of revolution as well and returned home where, at the age of nineteen, he became the secretary to the Swiss minister of war. He attained military rank (captain) and a reputation for being bright, diligent, and full of ambition. By

Antoine-Henri Jomini (below right) was born on March 6, 1779 in the small town of Payerne (Payerne church pictured right) in western Switzerland. His family was an old and influential one; his father Benjamin active in local politics. Jomini grew up with the French Revolution and the sight of French soldiers was something he was familiar with even as a boy. He was a teenager working in banking in Paris when the Swiss Revolution of 1798 broke out, largely instigated by the French at the proding of exiled Swiss radicals. Jomini’s father joined the revolutionary cause and served in various political roles in the Helvetian Republic. Antoine-Henri caught the fever of revolution as well and returned home where, at the age of nineteen, he became the secretary to the Swiss minister of war. He attained military rank (captain) and a reputation for being bright, diligent, and full of ambition. By twenty-one, he had command of a battalion. [i]

twenty-one, he had command of a battalion. [i]

It was during this time that he began a vigorous study of military history. John Shy suggests that Jomini was…

“obsessed by visions of military glory, with himself imitating the incredible rise of Bonaparte (below right) who was only ten years his senior, but in a telling phrase Jomini remembers being possessed, even then, by “le sentiment des principes” — the Platonic faith that reality lies beneath the superficial chaos

of the historical moment in enduring and invariable principles, like those of gravitation and probability. To grasp those principle, as well as to satisfy the more primitive emotional needs of ambition and youthful impatience, was what impelled him to the study of war. Voracious reading of military history and theorizing from it would reveal the secret of French victory.” [ii]

The Luneville Treaty of 1801 (see exerpts here) ended the Napoleonic Wars and Jomini returned to Paris where he maintained a devotion to the study and writing of military theory. He had been enthralled by Napoleon’s leadership. It is beyond disptue that the French had achieved a breakthrough in warfare and Jomini was about trying to find out how they had done it.

“Answering this question, persuasively and influentially, would be Jomini’s great achievement. The wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon generated a vast, receptive audience for the

kind of clear, simple, reassuring explanation that he would offer. Drawing overtly on the prestige of ‘science’ and yet almost religious in its insistent evangelical appeal to timeless verities, Jomini’s answer to this troubling question seemed to dispel the confusion and allay much of the fear created by French military victories.” [iii]

By 1804, Jomini had completed his Traité des grandes opérations militaires (Treastise on Great Milita ry Operations). He managed to ingratiate himself to General Michel Ney (right), leader of Bonaparte’s Sixth Corps, who had served for a time as French viceroy in Switzerland. Ney helped him to publish this first book. It would find its way to Napoleon and Jomini’s life would be forever changed. [iv]

ry Operations). He managed to ingratiate himself to General Michel Ney (right), leader of Bonaparte’s Sixth Corps, who had served for a time as French viceroy in Switzerland. Ney helped him to publish this first book. It would find its way to Napoleon and Jomini’s life would be forever changed. [iv]

Jomini’s principles would also find their way to West Point in the years preceeding the American Civil War. In Part III, I’ll discuss what those principles were.

[i] Hugh Chisholm, The Encyclopedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. 11th Ed, Volume XV. (Cambridge, England: At the University Press, 1911), 495. Accessed online 2/23/2008: here.

[ii, iii, iv] John Shy, “Jomini,” in Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 144 – 149.

Photos: Public Domain – Wiki Commons

CWI’s Top 50 Civil War Books of All Time

Civil War Interactive is accepting votes for the “Top 50 Civil War Books of All Time” list. You can vote here. They’re offering a nice incentive. Check it out.

wig-wags in Greek!

One of the very cool things about blogging is being able to see the sites from which some readers come (referrers as WordPress calls them). Tonight I saw for the first time a referral from a Google’s translation page. I clicked on the page and it appears that I have had a Greek reader checking out the courses page which describes my program! Here’s a screen print. Check it out…wig-wags in Greek! Made my day.

Railroad Disaster – Gare Montparnasse

Dimitri Rotov over at Civil War Bookshelf has an interesting post on his blog here in response to my two posts on railroads during the civil war: “Were the North and South Equally Matched… On the Rails” here and “Railroad Generalship” here.

The dramatic photo on his post is that of a French train whose brakes failed at Gare Montparnasse is 1895. If you’re so inclined, you can read about that disaster on the Danger Ahead: Historic Railway Disasters website here.

You can see a larger version of the photo here.

Railroad Generalship

Following up on yesterday’s post “Were the North and South Evenly Matched….on the Rails,” which is essentially about railroad management during the American Civil War, I wanted to add some additional information and links that will allow further exploration if you are so inclined.

Arguably one of the greatest advantages the North had was in one Herman Haupt (1817 – 1905), a “brilliant railroad engineer” recruited in May of 1862 by General D. C. McCallum to assume duties as Military Director and Superintendent of the USMRR (United States Military Railroad). Haupt was given the rank of Colonel and Lincoln gave him broad, albeit frequently challenged, powers.[i]

Photo Above: A.J. Russell, photographer. Gen’l H. Haupt, ca. 1862 or 1863. LOT 9209, no. 21 LC-DIG-ppmsca-10341

Photo Below: Haupt’s torpedo for quickly wrecking wooden bridges CALL NUMBER: LOT 9209, no. 57 [P&P]

More than any other, Haupt should receive credit for shaping and building the USMRR. He developed general guidelines for using the railroads to provide supplies for the Army of the Potomac. During the fall of 1862, Haupt experimented with methods of destroying and repairing railroads and rail bri

dges. He developed a torpedo that could destroy a standard Howe Truss bridge, a U-shaped device that could quickly and easily destroy rails by twisting them, and new and faster ways to lay and repair track. Haupt and his engineers also experimented with new ways of bridge construction. As a result, preassembled bridge trestles were mass-produced and then transported in boxcars to areas where bridges needed repair or replacement. The rebuilding of bridges and track after Confederate raids was a never-ending process. Haupt also developed ambulance cars with surgeons and special equipment that increased the chances of survival for the wounded.[ii]

This quote is from the report summary of the archaeological dig of the Alexandria, Virginia United States Military Railroad Station, a fascinating look at one of the busiest sites of the war.

By the war’s end, there were 10,000 men in the United States Military Railroad service. Many were ex-slaves.

Photo Below: Military railroad operations in northern Virginia: men using levers for loosening rails. REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZ62-90111

Dr. Christopher R. Gabel (OSU and Command and General Staff College) has written an interesting piece titled “Railroad Generalship: Foundation of Civil War Strategy” available here.

A bibliographical listing of works dealing with railroads during the Civil War (and other American conflicts) is available here.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i, ii] THE BONTZ SITE (44AX103) THE UNITED STATES MILITARY RAILROAD STATION (44AX105) Report Summary by Shirley Scalley, accessed online 1/20/2008 at http://oha.alexandriava.gov/archaeology/pdfs/bontz8.pdf

Were the North and South Evenly Matched…on the Rails?

One of the questions that was much debated in class was whether the North and South were evenly matched in the American Civil War? To get the discussion rolling, our professor threw out the following…

In his interesting study of the American Civil War, Archer Jones argues in Civil War Command and Strategy: The Process of Victory and Defeat (1992), that despite its superior numbers, the Union advantage was greatly diminished by the extent of Southern territory, the intrinsic superiority of the defense over the offense, and the problems of supplying armies over long distances. Jones also states that Northern industrial dominance also proved almost useless in a war that depended less on complex weaponry and ammunition than on the man with the rifle. In Jones’ opinion, the two sides were, in fact, almost evenly matched.[i]

Our task was to take a stand on whether the North and South were evenly matched. I decided to focus on the very specific area of railroad transportation during the war. Part of my interest in this area comes from my association with friend and rail historian Peter A. Hansen, the editor of Railroad History and author of a number of articles for Trains Magazine. I was able to interview him on the topic and have included a good part of that in the post below. The photo below will be included in the upcoming issue of Railroad History which “is given over to a nearly-encyclopedic overview of every company that ever built steam locomotives in America.”[ii] The principal contributor is John H. White, Jr., former curator of transportation at the Smithsonian Institution.

Photo: New Jersey Locomotive & Machine-built 4-4-0 Fred Leach near Union Mills, Va., on August 1, 1863, the year after it was built. Its stack and tender have taken cannon shot, and the main rod is missing. It became Orange and Alexandria Warrenton after the American Civil War. Library of Congress: 111-B-185.

Charles Roland, in his book An American Illiad: The Story of the Civil War, provides a strong case for the American Civil War being considered the “first complete railroad war.” He asserted that the North was well ahead of the South in railroad resources entering into the war with 20,000 miles of rails in 1860 to the South’s 10,000. The railroads of the north were better “linked into systems of trunk lines that covered the entire region.”[iii] There were other things that made the North’s railroads superior. “First, it was dotted with locomotive factories, concentrated particularly in Massachusetts, Paterson, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. All of them remained beyond the reach of Rebel forces, so production was never disrupted. It was never disrupted for want of materials, either, since most of the iron ore and coal were also concentrated in the North.”[iv]

“In addition, the North’s railroads were almost all built to the standard track gauge of 4’ 8 ½”. That meant the cars could be interchanged from one line to another without the need for time-consuming unloading and reloading of passengers and freight. In the South, the rail network was pretty thin to begin with, and the multiplicity of track gauges hampered operations even more. That was particularly important considering that most of the war was fought on Southern soil. With the notable exception of one shining moment at the First Battle of Bull Run, the South was never consistently able to rush men and materiel to the front by rail. There were just too many obstacles to such smooth operation in most of Dixie.”[v]

Photo above: Station at Hanover Junction, Pa., showing an engine and cars. In November 1863 Lincoln had to change trains at this point to dedicate the Gettysburg Battlefield. LOC: 111-B- 83.

Photo below: The four-tiered, 780-foot-long railroad trestle bridge built by Federal engineers at Whiteside, Tenn., 1864. A guard camp is also shown. Photographed by George N. Barnard. LOC: 111-B-482.

“It’s a little-known fact, but track gauge was the first big standardization issue – in any industry. It seems incredible to us from our modern perspective, but many people were slow to grasp the need for standardization. It had never been needed in the days when every village had its own blacksmith or carpenter, whose products never needed to be used in conjunction with those of the smithy or carpenter in the next town.”[vi]

Photo above: Tredegar Iron Works. Artist: Alexander Gardener, Public Domain, Wikipedia Commons.

“The South didn’t have a single locomotive factory of any consequence during the Civil War. Several had made a start during the 1840s and 1850s but failed to survive into the War years – including Richmond’s famous Tredegar Iron Works (see the American Civil War Center’s site at Tredegar Iron Works here). While the firm itself survived until 1956, they produced locomotives only from 1851 to 1860. Even as the storm clouds were gathering, they decided in late 1860 that the locomotive business wasn’t profitable for them, and they retooled the shop for other uses.

“[vii]

Photo right (cropped): James Noble Sr. from www.civilwarartillery.com/manufacturers.htm.

“Aside from Tredegar, the only wartime Southern locomotive factory that’s even marginally worth mentioning was James Noble and Son of Rome, Georgia. They produced only a few locomotives after 1855 and their factory was destroyed by Sherman’s army in 1864. What this means, of course, is that Southern railroads became increasingly dysfunctional as their locomotives were destroyed, since they had no means of replacing them. It also meant that their remaining locomotives were often old, and/or held together by any means possible.”[viii]

McPherson substantiates this in his book, Battle Cry of Freedom. He indicates that of the 470 locomotives built in the U.S. in 1860; only 19 were built in the South.[ix] According to Hansen, “the production of 470 locomotives in a single year may seem like a large number. But it is less surprising in light of two things. First, railroad mileage in the U.S. had surpassed 30,000, and about 2/3 of that total had been built in the previous decade. Just like new highways today, there was comparatively little traffic on new lines in their first couple of years, but usage mushroomed when people and businesses began to change their previous transportation preferences, and when businesses began to locate along the new lines. When a line began to see more traffic, whether two or five or eight years after it was built, new locomotives were needed to handle it. An economist might say that the need for rolling stock lagged the actual construction by a few years.”[x]

“Another thing to consider is the poor utilization of assets in those days. Just as standardization was a new concept in the middle of the 19th century, so, too, was asset utilization. The latter concept is quite recent indeed, not being fully understood until just the past decade or so. [Note: Consider that Southwest Airlines ran circles around its competitors for years, chiefly because SWA insisted on having an entire fleet of identical planes, and on keeping them on the ground for only 30 minutes at each stop. The underlying rationale for both policies was better asset utilization. The older airlines are still struggling to apply those same lessons.] A steam engine is a highly labor-intensive beast. It requires constant attention from fireman and engineer alike in order to get maximum productivity while it’s working, and it spends about two hours in the shop for every hour it spends on the road. That time is absolutely necessary to the proper functioning of the machine, since grates need to be shaken, ashes need to be dumped, and moving parts need lubrication. (Tallow was a common valve lubricant in those days before petroleum engineering, and applications had to be repeated frequently.) About once a month, the steam engine’s fire was dumped altogether so the tubes and flues could be inspected. The process of cooling an engine down, inspecting it, and firing it back up typically took 24-48 hours, so there’s a big chunk of unproductive time right there. So the bottom line is that they needed a lot of locomotives in those days!”[xi]

Brilliant Uses of Railroads

The South did have some success with the use of trains for troop transfer. Johnston’s use of the Manassas Gap Railroad to move his troops to Manassas Junction to reinforce Beauregard was brilliant and no doubt influenced the outcome of that engagement which so demoralized the North. Roland also reviews Bragg’s “almost incredible strategic use of the railroads” against Buell as the latter approached Chattanooga. “The Confederates half-circled the Union army by moving 30,000 from Tupelo, Mississippi, roundabout by way of Mobile and Atlanta to Chattanooga, a movement of some 776 miles.”[xii] Hansen felt that, “while it was true that Bragg’s campaign was a remarkable success in the face of daunting logistics, this was the exception that proves the rule.” The mere fact that he had to detour 776 miles in order to go 300 speaks to the paucity of railroads in the South. And even in his 776-mile detour, he had to port his troops on foot east of Montgomery, where the railroad ended, before he could load them on trains again near Columbus, Georgia. So yes, the railroads helped him win, but I submit that it was his audacity, combined with Buell’s dithering, that gave him the ability to make the best of a questionable asset.”[xiii]

Hansen added, that “it is worth noting that railroads were the whole reason Chattanooga had such strategic significance. The principal line from Richmond to Atlanta, and the line from Memphis to the east, converged there. Without Chattanooga, the South’s ability to move men and materiel by rail in their own territory was all but gone.”[xiv]

Thomas Ziek, Jr. came to the same general conclusion in his Master’s Thesis, “The Effects of Southern Railroads on Interior Lines during the Civil War.” He tried to determine whether or not the South enjoyed the advantage of interior lines and concluded that they did not.

The use of railroads during this conflict placed an enormous physical strain upon the limited industrial resources of the Confederacy, and a great strain upon the intellectual agility of the Confederate High Command. Based upon the evidence studied, and the time-space comparisons of both Northern and Southern railway operations, several conclusions can be drawn: the South entered the war with a rail system that was unable to meet the demands of modern war; the Confederate leadership understood the importance of the railroad and its importance to strategic operations early in the war, but were unwilling to adopt a course of action that best utilized their scarce assets; Union control, maintenance, and organization of its railway assets ensured that it would be able to move large numbers of troops at the strategic level efficiently from early 1863 to the end of the war. Based on these conclusions, the Confederacy lost the ability to shift troops on the strategic level more rapidly than the Union by 1863. This was a result of its physically weakened railroad system and military setbacks which caused Southern railroads to move forces over longer distances.[xv]

My conclusion, for this area of focus, is that the North and South were NOT equally matched either in their physical rail assets nor in their management of those assets. While the South had some moments of brilliance in their use of railroads, they simply did not have the infrastructure to maintain, let alone expand, the railroads of their region to their greatest advantage.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i] White, Charles, AMU CW500.

[ii, iv, v, vi, vii, viii, x, xi, xiii, xiv] Hansen, Peter A., Personal interview. Sept. 9, 2007

[iii, xii] Roland, Charles P. An American Iliad: The Story of the Civil War

[ix] McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom

[xv] Ziek, Thomas G., Jr., “The Effects of Southern Railroads on Interior Lines During the Civil War.” A Master’s Thesis.

Death and Injury on the Battlefield – Part I

On November 24th, I posted a piece on the impact of disease on soldiers in the Civil War [see “On Lice, Disease and Quinine” here]. The following discusses the other side of death during the war, the experience on the battlefield. Please be aware the the following is very graphic. [Photo to left: One of Ewell’s Corps as he lay on the field, after the battle of the 19th May, 1864. ]Battle injuries in the civil war were horrific and many led to death. The journals of soldiers and photographs of the dead tell of injury and death caused by cannon balls, grapeshot, canister, musket balls, bayonets, clubbing and more. Men were decapitated, cut in two, blown apart, shot in head, body, and/or extremities, bashed in the face or skull, disemboweled, burned, dragged, drowned, and/or suffered broken bones. John Beatty provided a glimpse of the carnage typical on most Civil War battlefields in a journal entry describing his pass through the battlefield of Stone River in Tennessee, early in 1863.

I ride over the battle-field. In one place a caisson and five horses are lying, the latter killed in harness, and all fallen together. Nationals and Confederates, young, middle-aged, and old, are scattered over the woods and fields for miles. Poor Wright, of my old company, lay at the barricade in the woods which we stormed on the night of the last day. Many others lay about him. Further on we find men with their legs shot off; one with brains scooped out with a cannon ball; another with half a face gone; another with entrails protruding; young Winnegard, of the Third, has one foot off and both legs pierced by grape at the thig

hs; another boy lies with his hands clasped above his head, indicating that his last words were a prayer. Many Confederate sharpshooters lay behind stumps, rails, and logs, shot in the head. A young boy, dressed in the Confederate uniform, lies with his face turned to the sky, and looks as if he might be sleeping. Poor boy! what thoughts of home, mother, death, and eternity, commingled in his brain as the life-blood ebbed away! Many wounded horses are limping over the field. One mule, I heard of, had a leg blown off on the first day’s battle; next morning it was on the spot where first wounded; at night it was still standing there, not having moved an inch all day, patiently suffering, it knew not why nor for what. How many poor men moaned through the cold nights in the thick woods, where the first day’s battle occurred, calling in vain to man for help, and finally making their last solemn petition to God![1]

Linderman posits that, even though the men fighting in the Civil War should have been more used to gore and death than those fighting in the next century, “when young soldiers first saw bullets, cannonballs, grapeshot, and canister strike others, their shock was profound. The first surprise was death’s suddenness,” a man alive and animated next to them one moment, and the next, lifeless and shattered. [2]Men splattered with the insides of the man next to them were even more impacted. Also shocking was the magnitude of death. It was not uncommon to see thousands of bodies after a single battle.[3]

Many men died agonizing deaths after lying injured on the field for hours or days. Contributing to this were standing orders that prevented a man from stopping his forward motion to help a fallen comrade. Some men were also fearful that doing so would imply cowardice on their part. Also, rarely could a truce be made to remove the injured and dead from the battlefield. The resulting experience for the injured was atrocious. Methods and procedures that would allow for application of first aid and then rapid transport to field hospitals were simply non-existent.

Disposal of bodies was often done carelessly and with little decorum if at all. Given the magnitude and ghastliness of the task, it is little wonder. Depending on the season, bodies awaiting burial, or even after careless burial, bloated and decayed in the heat and could be eaten by animals and insects. [Photo at right depicts the burial of soldier on one side and while an enemy soldier is left unburied.]Next installment… “Injuries on the Battlefield.”

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

Photos from the Library of Congress

[1] John Beatty, The Citizen-Soldier: The Memoirs of a Civil War Volunteer [book on-line] (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998, accessed 28 September 2007), 211; available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=26979264; Internet.

[2] Gerald Linderman, Embattled Courage: The Experiences of Combat in the American Civil War, 124.

[3] Ibid.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part IX: The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability

A review of the literature reveals – not surprisingly – a lack of agreement over whether the American Civil War was inevitable. Given the fact that it did occur, the question under consideration might be better stated as “at what point in time” did the American Civil War became unavoidable.

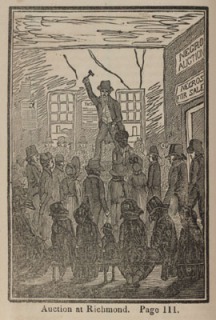

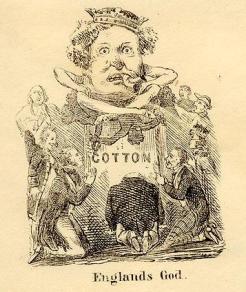

Some would argue that war became predestined at the point when the slave trade was first introduced to the colonies. Others have suggested that civil war became preordained when the founding fathers created a Constitution that professed freedom for all but failed to deal with the country’s practice of chattel slavery (image left of slave auction at Richmond). But portions of the country had demonstrated a willingness to move away slavery. And there was some indication that even slave owners in the south did not expect the practice to go on indefinitely. Certainly the rise of King Cotton, made feasible by the invention of the cotton gin and cotton varieties more suited to the southern climate, slowed the inclination to move away from slavery. Even so, the country had opportunity and demonstrated an ability to find compromise on the issues surrounding slavery time and again and could have

Some would argue that war became predestined at the point when the slave trade was first introduced to the colonies. Others have suggested that civil war became preordained when the founding fathers created a Constitution that professed freedom for all but failed to deal with the country’s practice of chattel slavery (image left of slave auction at Richmond). But portions of the country had demonstrated a willingness to move away slavery. And there was some indication that even slave owners in the south did not expect the practice to go on indefinitely. Certainly the rise of King Cotton, made feasible by the invention of the cotton gin and cotton varieties more suited to the southern climate, slowed the inclination to move away from slavery. Even so, the country had opportunity and demonstrated an ability to find compromise on the issues surrounding slavery time and again and could have  conceivably continued to do so had other factors not pushed the country to war.

conceivably continued to do so had other factors not pushed the country to war.

Sectional differences, well evident even in colonial days, had the potential to make civil war predestined but historian Avery Craven suggests otherwise. “Physical and social differences between North and South did not in themselves necessarily imply an irrepressible conflict. They did not mean that civil war had been decreed from the beginning by Fate.”[i] He points out that the federal system created by the founding fathers had room for differences and that England herself adopted the model of American federalism and used it to manage widely disparate regions.[ii]

Kenneth Stampp in his work, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink, suggests that “…1857 was probably the year when the North and South reached the political point of no return — when it became well nigh impossible to head off a violent resolution of the differences between them.”[iii] Stampp identified three primary factors that catapulted the country toward disunion within that twelve month period.

Kenneth Stampp in his work, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink, suggests that “…1857 was probably the year when the North and South reached the political point of no return — when it became well nigh impossible to head off a violent resolution of the differences between them.”[iii] Stampp identified three primary factors that catapulted the country toward disunion within that twelve month period.

-

The first was the increase in sectional conflict centered on Kansas.

-

The second was President Buchanan’s fall from grace among most of the Northerners who had voted for him after he supported the Lecompton Constitution and thus broke his pre-election promises. This sparked one of the most vicious debates in Congress and led to…

-

the third happening which was the crisis that occurred in the national Democratic Party from which “it did not recover until after the Civil War.”[iv] That schism in the party opened the way for Abraham Lincoln’s candidacy for the presidency which in turn raised sectional tensions between North and South to new heights.

Civil War historiographer Gobar Boritt suggests that the American Civil War only became inevitable after the attack on Fort Sumter (pictured right after surrender) and with this I agree. “The popular uprising, North and South, that followed the fight over Sumter, combined with willing leadership on both sides, made the Civil War inevitable. It was not that before.”[v] Boritt acknowledges that “the probability of war” continued to grow in the 1850s, but that “the country’s fate was not sealed until the ides of April, 1861.”[vi]

Civil War historiographer Gobar Boritt suggests that the American Civil War only became inevitable after the attack on Fort Sumter (pictured right after surrender) and with this I agree. “The popular uprising, North and South, that followed the fight over Sumter, combined with willing leadership on both sides, made the Civil War inevitable. It was not that before.”[v] Boritt acknowledges that “the probability of war” continued to grow in the 1850s, but that “the country’s fate was not sealed until the ides of April, 1861.”[vi]

My conclusion is that the American Civil War was not inevitable but was, rather, the result of a confluence of factors which – taken in aggregate and flared by extremists – resulted in a war unwanted by the majority of Americans. Contributory to the war was the influence of specific individuals – not the least of which was Abraham Lincoln himself. Other politicians, by their action or inaction at critical moments, also had part to play in the circumstances that led to war. Debate over the war’s inevitability has been and will continue to be rigorous.

This post concludes a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes, Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity, Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control, and Part VIII: The Influence of the Individual.

As always, I invite your comments.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

___________________

Photo Credits:

Slave Auction, Richmond, Virginia, 1830. [Source: University of Virginia. Imaged reference: Bourne01. George Bourne, Picture of slavery in the United State of America. . . (Boston, 1838).

Cotton – England’s God [Pictorial envelope] [LOC CALL NUMBER PR-022-3-14-19]

Fort Sumter after evacuation, flagpole shot away twice. [Stereograph], 1861. [LOC CALL NUMBER PR-065-798-22

Endnotes:

[i] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 1.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Stampp, Kenneth M. America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. Vers. [book on-line] Internet. Questia.com.New York: Oxford University Press. 1990. available from questia.com, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?action=openPageViewer&docId=24268497 (accessed September 1, 2007), viii.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] ” ‘And the War Came’? Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 6.

[vi] Ibid.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes and Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity.

___________________

Political discord represents yet another candidate for the war’s cause. Late historian William E. Gienapp (pictured right) suggests that “however much social and economic developments fueled the sectional conflict, the coming of the Civil War must be explained ultimately in political terms, for the outbreak of war in April 1861 represented the complete breakdown of the American political system. As such, the Civil War constituted the greatest single failure of American democracy.”[i]

Political discord represents yet another candidate for the war’s cause. Late historian William E. Gienapp (pictured right) suggests that “however much social and economic developments fueled the sectional conflict, the coming of the Civil War must be explained ultimately in political terms, for the outbreak of war in April 1861 represented the complete breakdown of the American political system. As such, the Civil War constituted the greatest single failure of American democracy.”[i]

Gienapp poin ts to the role of slavery as the underlying cause of the sectional conflict. “Without slavery it is impossible to imagine a war between the North and the South (or indeed, the existence of anything we would call “the South” except as a geographic region).”[ii] He also asserts that America’s slave heritage was completely associated with race. That is, had the slaves brought to America been white, the practice would have disappeared much earlier.[iii] But an argument asserting slavery as chief cause of the war neglects the fact that not only was it older than the republic, but “for over half a century following adoption of the Constitution, the institution had only sporadically been an issue in national politics, and it had never dominated state politics in either section.”[iv] What changed? It was the rise of the slavery issue in American society; that is, the heightened awareness of it. This development was rooted in a number of changes in American society in the first half of the nineteenth century already addressed.[v]

ts to the role of slavery as the underlying cause of the sectional conflict. “Without slavery it is impossible to imagine a war between the North and the South (or indeed, the existence of anything we would call “the South” except as a geographic region).”[ii] He also asserts that America’s slave heritage was completely associated with race. That is, had the slaves brought to America been white, the practice would have disappeared much earlier.[iii] But an argument asserting slavery as chief cause of the war neglects the fact that not only was it older than the republic, but “for over half a century following adoption of the Constitution, the institution had only sporadically been an issue in national politics, and it had never dominated state politics in either section.”[iv] What changed? It was the rise of the slavery issue in American society; that is, the heightened awareness of it. This development was rooted in a number of changes in American society in the first half of the nineteenth century already addressed.[v]

As mentioned in previous posts in this series, the abolitionist movement did a great deal to raise that awareness. But Gienapp suggests that “it was the politicians themselves, as part of the struggle for control of the two major parties, wh o ultimately injected the slavery issue into national politics.”[vi] The key development was the introduction in Congress in 1846 of the Wilmot Proviso, which prohibited slavery from any territory acquired from Mexico, by a group of Van Burenite Democrats who were angry with President James K. Polk (pictured right) and his southern advisers. Once the slavery issue, in the shape of the question of its expansion into the western territories, entered the political arena, it proved impossible to get it out. The issue took on a life of its own, and when politicians tried to drop the issue after 1850, they discovered that many voters were unwilling to acquiesce.[vii]

o ultimately injected the slavery issue into national politics.”[vi] The key development was the introduction in Congress in 1846 of the Wilmot Proviso, which prohibited slavery from any territory acquired from Mexico, by a group of Van Burenite Democrats who were angry with President James K. Polk (pictured right) and his southern advisers. Once the slavery issue, in the shape of the question of its expansion into the western territories, entered the political arena, it proved impossible to get it out. The issue took on a life of its own, and when politicians tried to drop the issue after 1850, they discovered that many voters were unwilling to acquiesce.[vii]

Gienapp makes a good case for the war’s true cause in the following discourse.

A second critical development, intimately related to the first, was the crystallization of rival sectional ideologies oriented toward protecting white equality and opportunity. Increasingly, each section came to see the other section and its institutions as a threat to its vital social, political, and economic interests. Increasingly, each came to think that one section or the other had to be dominant. Informed by these ideologies, a majority of the residents of each section feared the other, and well before the fighting started the sectional conflict represented a struggle for control of the nation’s future.

It fell to the political system to adjudicate differences between the sections and preserve a feeling of mutual cooperation and unity. And for a long time the political system had successfully defused sectional tensions. Because it brought northern and southern leaders together, Congress was the primary arena for hammering out solutions to sectional problems. In various sectional confrontations–the struggle over the admissi

on of Missouri as a slave state in 1819-21, the controversy over nullification and the tariff in 1833, the problem of the status of slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico in 1850, and the struggle over the proslavery Lecompton constitution in 1858-Congress had always managed to find some acceptable way out of the crisis.

Yet the American political system was particularly vulnerable to sectional strains and tensions. One reason was the institutional structure of American politics. The Civil War occurred within a particular political institutional framework that, while it did not make the war inevitable, was essential to the coming of the war.

Integral to this institutional framework was the United States Constitution. While some aspects of the Constitution retarded the development of sectionalism, it contained a number of provisions that strengthened the forces of sectional division in the nation. No constitution can anticipate all future developments and conclusively deal with all controversies that subsequently arise. The purpose in analyzing the Constitution’s role in the sectional conflict is not to fault its drafters or condemn it as a flawed document, but rather to indicate the importance of certain of its clauses for the origins of the war.

One signifi

cant feature of the Constitution was its provision for amendment. Lurking beneath the surface in the slavery controversy was white Southerners’ fear that the Constitution would be amended to interfere with the institution. In advocating secession after Abraham Lincoln’s election, Governor Andrew B. Moore of Alabama (pictured above) predicted that the Republicans would quickly create a number of new free states in the West, which “in hot haste will be admitted to the Union, until they have a majority to alter the Constitution. Then slavery will be abolished by law in the States.”[viii]

The fear, uncertainty and doubt associated with this possibility, on the part of the Southern political establishment, pushed the country toward war.

The next post: “The Influence of the Individual.”

For further reading, I recommend The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War by Michael F. Holt and Why the Civil War Came, edited by Gabor S. Boritt.

© 2007 Rene Tyree

_________________________

Photo credits:

Historian William E. Gienapp. Source: Harvard Gazette Archives, Issue: April 07, 2005.

Poster Announcing Sale and Rental of Slaves, Saint Helena (South Atlantic), 1829. Source: The Atlantic Slave Trade and

Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record., Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr., The Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Image H003.

President James K. Polk

Cropped image of the constitution of Kansas

Governor Andrew B. Moore of Alabama. Source: Alabama Department of Archive and History

[i] William E. Gienapp, “The Crisis of American Democracy, the Political System and the Coming of the Civil War,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt [book on-line] (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, accessed 1 September 2007), 82; available from questia.com http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=78779127; Internet., [ii] Ibid., [iii] Ibid., [iv] Ibid., [v] Ibid., [vi] Ibid., 83., [vii] Ibid., [viii] Ibid., 86.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part III – The Antebellum South

The Southern man aspired to a lifestyle that had, as utopian model of success, the English country farmer. Jeffersonian agrarianism was valued over Hamiltonian industrialization.

To achieve success, cheap labor in the form of slavery was embraced. The capital of the south was invested in slaves even after modernized farming equipment became available. More land was needed to produce more crops which required, in turn, more slaves. This cycle repeated until some 4 million slaves populated the South by mid-century. The system became self-perpetuating because – as posited by historian James McPherson – slavery undermined the work-ethic of both slave and Southern whites. The slave obviously had limited opportunity for advancement. Manual labor became associated with bondage and so lacked honor. The result was a limited flow of white immigrants to the south who could provide an alternative labor force and an increase in the migration of southern whites to free states.[i]

became associated with bondage and so lacked honor. The result was a limited flow of white immigrants to the south who could provide an alternative labor force and an increase in the migration of southern whites to free states.[i]

Simply stated, the South chose not to modernize. It hosted little manufacturing. It also lacked a well developed transportation system (a fact that would prove key to the conduct of the war).

White supremacy was simply a fact. Part of the responsibility of owning slaves was to care for their material needs as you would children. White southern children grew up with a facility for “command” and became a part of what was viewed by many as a southern aristocracy.[ii]

According to historian Avery Craven, “three great forces always worked toward a common Southern pattern. They were:

- a rural way of life capped by an English gentleman ideal,

- a climate in part more mellow than other sections enjoyed, and

- the presence of the Negro race in quantity. More than any other forces these things made the South Southern.”[iii]

Next post – The Antebellum North

For additional reading…

On Jeffersononian Agrarianism see the University of Virginia site here.

[i] James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 10., 41.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 33.

Photo Credits:

Watercolor View of the West Front of Monticello and Garden (1825) by Jane Braddick. Peticolas. The children are Thomas Jefferson’s grandchildren. Public Domain [Source: Wikipedia Commons]

Inspection and Sale of a Slave. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Digital ID: cph 3a17639 Source: b&w film copy neg.

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-15392 (b&w film copy neg.)

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part II – Antebellum America

In the last post, I kicked off a series looking at the causes of the American Civil War. Study of 19th century Antebellum America reveals a young country experiencing incredible change. Its rate of growth in almost all measures was unrivaled in the world. Its population was exploding through both immigration and birth rate. The push for land drove expansion of its boundaries to the south and west. Technological development enabled modernization and industrialization. The “American System of Manufactures” created the factory system.[i] People became “consumers” rather than “producers” of goods and this changed many social aspects of society.

The majority of Americans held a Calvinist belief structure. Puritan influence was strongest in New England. Immigration of large numbers of Catholic Irish created new cultural and ethnic tension. Irish Catholics tended to oppose reform and clustered in the lower classes of the North while native Yankee Protestants predominated in the upper and middle-classes.[ii] The century was marked by enthusiastic evangelical reformation movements. [Note: Jonathan D. Sassi has a concise description of the antebellum evangelical reformation movement in America here.]

A two-party political system had emerged by 1830. “Issues associated with modernizing developments in the first half of the century helped to define the ideological position of the two parties and the constituencies to which they appealed.”[iii]  Democrats inherited the Jeffersonian commitment to states’ rights, limited government, traditional economic arrangements, and religious pluralism; Whigs inherited the Federalist belief in nationalism, a strong government, economic innovation, and cultural homogeneity under the auspices of established Protestant denominations.[iv]

Democrats inherited the Jeffersonian commitment to states’ rights, limited government, traditional economic arrangements, and religious pluralism; Whigs inherited the Federalist belief in nationalism, a strong government, economic innovation, and cultural homogeneity under the auspices of established Protestant denominations.[iv]

The fight for democracy and the fight for morality became one and the same.[v] “The kingdom of heaven on earth was a part of the American political purpose. The Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Scriptures were all in accord.”[vi]

Distinct Northern and Southern cultures began to emerge early in the country’s history. These differences became more marked as the pressures that accompanied the nation’s incredible growth, territorial expansion and social change manifested themselves. Sectional identities and allegiances became increasingly important.

Next post – the Antebellum South.

Photo Above: Th. Jefferson, photomechanical print, created/published [between 1890 and 1940(?)]. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Presidential File. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-2474. This print is a reproduction of the 1805 Rembrandt Peale painting of Thomas Jefferson held by the New-York Historical Society.

For further reading:

- Jonathan D. Sassi has a concise description of the antebellum evangelical reformation movement in America here.]

- I recommend Puritanism in New England written by Donna M. Campbell and accessible on the Washington State University site here.

- James M. McPherson’s Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction has an excellent review of Antebellum America.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i] Historian James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 10, [ii] Ibid., 23, [iii] Ibid., 25, [iv] Ibid., [v] Ibid., 13, [vi] Ibid.

The Civil War as Revolution – Part I

[Note: This post is part of a series on The Civil War as Revolution which is available at the following links: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

————-

Earlier this month, I posted some thoughts on Abraham Lincoln as revolutionary. It ties to one of the topics we were asked to consider this term, whether the Civil War should be considered the second American revolution. I suspect it is an essay question in many American history programs dealing with the Civil War. I’d like to explore this over the next several posts. A proper place to start is with the question, what is revolution?

![Fist [Source Wikopedia Commons]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Fist.png/421px-Fist.png) According to William A. Pelz in his study on the history of German social democracy, “revolution” comes from the German word “Ugmwälzung” which means “rotation,” as in the turning of an axle. He posits that “in the socio-political realm, revolution means the displacement of a state, governmental, social and economic system by another, higher, more developed state, governmental, social and economic system… Two things are essential to the concept of revolution: that the rotation (Ugmwälzung) be comprehensive and fundamental–that everything old and antiquated be thrown out, weeds torn out by their roots; that a higher and better state replace that which has been done away with. Both conditions must be maintained.”[i] Thus social revolution results in nothing less than transformation.

According to William A. Pelz in his study on the history of German social democracy, “revolution” comes from the German word “Ugmwälzung” which means “rotation,” as in the turning of an axle. He posits that “in the socio-political realm, revolution means the displacement of a state, governmental, social and economic system by another, higher, more developed state, governmental, social and economic system… Two things are essential to the concept of revolution: that the rotation (Ugmwälzung) be comprehensive and fundamental–that everything old and antiquated be thrown out, weeds torn out by their roots; that a higher and better state replace that which has been done away with. Both conditions must be maintained.”[i] Thus social revolution results in nothing less than transformation.

- Painting by Eugene De la Croix (Charenton-Saint-Maurice, 1798 – Paris, 1863) July 29, Liberty guiding the people. Musée du Louvre. Public Domain

Pelz offers two examples of undisputable social revolution. The first, not surprisingly, is the French Revolution, “…the revolution par excellence…that swept away the last remains of medieval feudalism and created the foundation of modern bourgeois society.”[ii] The second example – though hardly resembling the first – was none the less more profound. It was triggered by “the introduction of machine work, which fundamentally altered the nature of work and thereby the basis of state and social life. Every sphere of human existence was penetrated by this revolution (Umwälzung). These two organically related revolutions (Umwälzungen) born of the same impetus, only manifesting themselves differently, are probably the most important revolutions known to history. They toppled and purged from top to bottom and brought humanity forward with a violent jolt.”[iii]

Revolution in politics has been described as “fundamental, rapid, and often irreversible change in the established order.”[iv]

- Da Vinci

Revolution involves a radical change in government, usually accomplished through violence[,] that may also result in changes to the economic system, social structure, and cultural values. The ancient Greeks viewed revolution as the undesirable result of societal breakdown; a strong value system, firmly adhered to, was thought to protect against it. During the Middle Ages, much attention was given to finding means of combating revolution and stifling societal change. With the advent of Renaissance humanism, there arose the belief that radical changes of government are sometimes necessary and good, and the idea of revolution took on more positive connotations. John Milton regarded it as a means of achieving freedom, Immanuel Kant believed it was a force for the advancement of mankind, and G.W.F. Hegel held it to be the fulfillment of human destiny. Hegel’s philosophy in turn influenced Karl Marx.[v]

Historian James McPherson offers the following as a “common sense” definition for revolution: “an overthrow of the existing social and political order by internal violence.”[vi] With this as background the question becomes, does the American Civil War qualify for revolution status? Was it sufficiently transforming?

- Mark Twain

More in tomorrow’s post but let me leave you with this quote from Mark Twain.

No people in the world ever did achieve their freedom by goody-goody talk and moral suasion: it being immutable law that all revolutions that will succeed must begin in blood, whatever may answer afterward.

– A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

[Addendum: This series on The Civil War as Revolution continues at the following links: , Part II, , Part III,, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

[i] Pelz, William A. and William A. Pelz, eds. Wilhelm Liebknecht and German Social Democracy: A Documentary History. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994), 264-265, Book on-line. Available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=15096547. Internet. Accessed 13.October 2007.

[ii] Ibid., 265.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Encyclopedia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2007

[v] Ibid.

[vi] James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 16.

Hardee’s Tactics

I mentioned in the last post that I had begun reading Douglas Southall Freeman’s R.E. Lee: A Biography. In the “Foreward,” Freeman mentions that in his references to military terminology, he has applied “Hardee’s Tactics” which was used by both armies. Fortunately, I found a copy on the web. I discovered – you all may have found it long ago – the fantastic U.S. Regulars Archives which has digitized copies of a variety of tactics documents. I’ve filled under military history.

Depictions of Slavery in Confederate Currency

I found an interesting site with primary resources over the weekend on the unusual topic of Confederate currency and their images of slavery. The Louisiana State University’s United States Civil War Center Civil War Collections & the Civil War Book Review presents in an online exhibit, Beyond Face Value: Depictions of Slavery in Confederate Currency.

Scholars working on the project included: John M. Coski, Evaluator, historian and library director at The Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia; Jules d’Hemecourt, Principal Scholar, who teaches at Louisiana State University in the Manship School of Mass Communication;Harold Holzer, Guest Scholar and Vice President for Communications at The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Henry N. McCarl, Guest Scholar, is a Professor of Economics in the School of Business at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Also contributing were: Vic Erwin, Web Designer, Sylvia Frank, Exhibit Editor, andLeah Wood Jewett, Project Director.

The Civil War Center at Louisana State University includes a number of print resources including a large collection of Civil War related books. All online collections can be found at http://www.cwc.lsu.edu/exhibitions.html. These include Civil War Book Review, also available at http://civilwarbookreview.com, which provides critical review of contemporary books on the Civil War.

The site is a real gem.

Chicken Guts

Yesterday, Dimitri Rotov made my day by calling “the Union war effort” “jiggery-pokery.” Ha! This was in reference to my mention of Bruce Catton’s word for it – slapdash – in my post here.

I went in search of Civil War slang.

This was my favorite find although I’m not entirely sure how to put it in a sentence. I’m open for suggestions.

Chicken Guts – gold braid used to denote officer ranks

Why Men Fought in the Civil War

Men who hurried to sign up for the armies of the North and South in the early years of the American Civil War, joined – to varying degrees – for the follow reasons: out of a sense of duty and honor to country (whether North or South), to feel and prove oneself “manly,” a trait tied closely to notions of courage, and in search of adventure and the glory and excitement of battle. Historian James McPherson’s readings of thousands of letters written by soldiers revealed that duty and honor were closely linked to “masculinity” in Victorian America and war presented an opportunity to prove one’s self a man.[i]

In the South, the ideas of duty and honor were most prevalent in the upper classes while such notions were less class specific in the North. Some men from both sides shared a sense of shame in “not” serving and this need to carry one’s self well remained a motivating factor for many of the men who actually “did” the fighting.

Money was not an apparent motivation for joining the military. Most men – and their families – sacrificed economically as a result of their service. Many gave up the best years of their lives, if not life itself. Later in the war, when recruits were harder to find, motivations broadened. Money may have become more of a factor and was certainly such for those who scammed the system to obtain more than one signing bonus.

Regardless of what brought men to war, their performance as soldiers varied. A good many served well. Others discovered within themselves a lack of courage and joined the ranks of men who shrank into the shadows during battles, assuring themselves safety from injury or death but not from the stigma of “coward” and “shirker.” As the war dragged on, survivors began to change their perspectives on what constituted courage and cowardice as well as their notions of the proper conduct of war.

Photo of D.W.C. Arnold, a private in the Union Army. Photo from The National Archives [Ref. 111-B-5435

__________________________

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

[i]James M. McPherson. For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 25.

On Edward C. and CDVs