Archive for December 2008

Great Post on the Origins of Know Nothings

Elektratig, one of my favorite blogs on Antebellum American history, has a post worth reading on the origins of the name “Know Nothing” that you can read here. Recommended reading for those following my series on Know Nothings and/or Antebellum America.

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 2

In the 1830s and 1840s, Americans had rediscovered a fascination with fraternalism discarded earlier in the century “when anti-Masonry led to public suspicion of secret societies.” (1) This was the era of the Odd Fellows, the Foresters, the Good Fellows and the Druids, the Red Men and the Heptasops. (2)

James McPherson marks the beginning of the movement that would lead to the “Know Nothing” American Party in the 1840s, when nativist parties flared and then cooled after the elections of 1844. (3) Relief from depression calmed tensions between native and foreign-born workers just in time for the massive influx of Europeans that resulted from that continent’s potato blight. (4) But American nativist sentiments continue to simmer and “on a late December evening in 1844, thirteen men gathered in the home of printer Russell C. Root in New York City” to form a group calling itself the American Brotherhood. The name was eventually changed to “Order of United Americans (OUA).” Its goals, outlined in a “code of principles,” were “to release our country from the thralldom of foreign domination.” This marked the birth of a nativist fraternity…and formed the nucleus of a far larger nativist effort than ever before. (5)

Membership in the Order of United Americans was limited to white men, twenty-one years of age or older, native born and Protestant. Its leaders were reasonably affluent and good organizers albeit from the “margins of the establishment.” This was a secret society replete with mysterious rituals and procedures that gave it an “illusion of antiquity.” (6)

Central to its structure was the magical triad. There were three levels of authority (local chapter, state chancery, and national archchancery), three chancellors sent from chapter to chancery, three archchancellors sent on to national. But there was only one leader of the OUA (limited to a single year term) and in the language of the lodge vogue he was called the arch grand sachem. By 1850, he ruled over a truly national domain with groups in New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Missouri, and Ohio. (6)

Gradually the organization began to become politicized and attracted “many conservative Whigs whose nativist ideology conveniently intersected with political needs in a time of party disarray.” (7)

—

1. David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 106.

2. Ibid.

3. James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 130.

4. Ibid.

5. David H. Bennett, The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History, 105.

6. Ibid, 107.

7. Ibid., 110.

Political History Word of the Day – Jingoistic

I ran across the word “jingoistic” tonight in my reading of a fascinating book, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement by David H. Bennett.

I ran across the word “jingoistic” tonight in my reading of a fascinating book, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement by David H. Bennett.

jingoistic

adjective

fanatically patriotic [syn: chauvinistic]

jin·go·ism

Extreme nationalism characterized especially by a belligerent foreign policy; chauvinistic patriotism.

jin’go·ist n., jin’go·is’tic adj., jin’go·is’ti·cal·ly adv.

Here is a snippet from Bennett’s book to show the context of his use of the word.

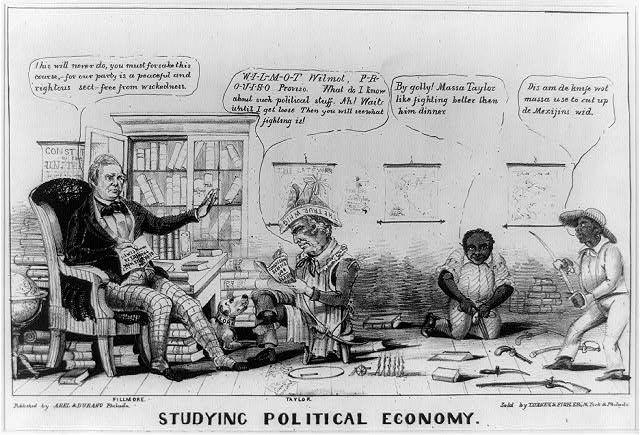

The greatest upheaval was the clash between the North and South. The issue of slavery, and the sectional conflict it helped to generate and exacerbate, was inextricably connected to territorial expansion. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 temporarily resolved that issue, setting the famous line (36° 30″) to the Pacific, north of which the South’s “peculiar institution” could not be extended. But the question flared anew with the Mexican War and the prospect of a rich California territory and a new estate in the desert and mountain West available for American settlement and development. This war of expansion did not unify the country as have international conflicts in some tranquil times. Nor did that other jingoistic outburst against the British in the debate over division of the Oregon territory in the far Northwest. (2)

(1) jingoistic. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/jingoistic (accessed: December 20, 2008)

(2) David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement [book on-line] (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988, accessed 20 December 2008), 95; available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=105437276; Internet.

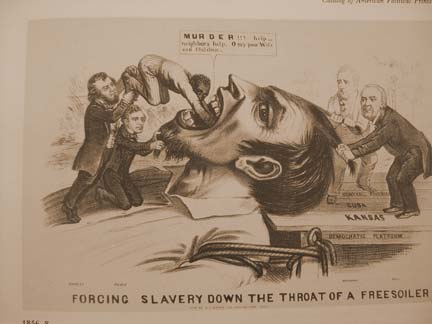

On Free Soilers – 2

A key reason that “Free Soilers” feared the South, and particularly slaveholders, was because of the political power they wielded in the national parties and government. This resentment found as “epithet the term ‘Slave Power,’ which Northern politicians of both parties used to denounce the political pretensions of slaveholders. Prohibiting slavery from the territories was the easiest way to prevent the admission of more slave states and thus to stop the growth of the political power of slaveholders.”(1)

Fear of the South’s power manifest itself in the resentment and writings of politicians such as David Wilmot (Wilmot Proviso).

“I am jealous of the power of the South….The South holds no prerogative under the Constitution, which entitles her to wield forever the Scepter of Power in this Republic, to fix by her own arbitrary edit, the principles of policy of this government, and to build up and tear down at pleasure… Yet so dangerous do I believe the spirit and demands of the Slave Power, so insufferable its arrogance, if I saw the way open to strike an effectual and decisive blow against its domination at this time, I would do so, even at the temporary loss of other principles.” (1)

Even within parties there was resentment between North and South. Michael Holt provides a quote from a young Massachusetts Whig that shows the visceral nature of the resentment of Northerners toward their party colleagues from the South.

“They have trampled on the rights and just claims of the North sufficiently long and have fairly shit upon all our Northern statesmen and are now trying to rub it in and I think now is the time and just the time for the North to take a stand and maintain it till they have brought the South to their proper level.” (1)

While the reasons for this resentment were complex, one clear fear was that the South would dictate the expansion of slavery into Western territories and this would degrade the value of free white labor and thus the potential for movement of the Northern-based labor ethic into those territories.

(1) Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s, (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1978), 51.

The Cycles of History: The Panic of 1857

Interesting insights this morning from Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War by Eric Foner. I’ll let you draw your own parallels to our current challenges.

“As they were to do many times subsequently, Republicans blamed the Panic not on impersonal economic forces, but on the individual shortcomings of Americans, particularly their speculation in land and stocks which had reached ‘mania’ proportions in the years preceding the crash, and on generally extravagant living. The Cincinnati Gazette defined the basic economic problems as an overexpansion of the credit system, rooted in too many ‘great speculations.’ But speculation was only one aspect of the problem of general extravagance. ‘We have been living too fast,’ complained the Gazette. ‘Individuals, families, have been eagerly trying to outdo each other in dress, furniture, style and luxury.’ The Chicago Press and Tribune likewise blamed ‘ruinous extravagance’ and luxurious living’ for the economic troubles, and both papers urged a return to ‘republican simplicity,’ and the frugal, industrious ways of the Protestant ethic.”

Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). 24.

Railroad Historian Inteview – Peter A. Hansen – 12/4

My buddy Peter Hansen, who contributed to my series of posts on Civil War railroads here, will be interviewed on the radio program Up to Date Thursday, December 4th from 11 AM – Noon Central Time about the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art special exhibit of Art in the Age of Steam: Europe, America and the Railway, 1830-1960. (I’m hoping we can finagle a personal tour with Pete as guide.) Of note in Pete’s bio below, (which I’ll admit I snagged from KCUR’s website in hopes that they’d appreciate the publicity), is a heads up about a story he’s written for Trains on Lincoln and the railroads. It’s well worth the read when it comes out next year.

Image: Pierre Fix-Masseau, French (1905 - 1994). Exactitude. 1932. Color Lithograph, 39 1/2 x 24 1/2 inches (99.7 x 61.6 cm.) Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the Modernism Collection. Gift of Norwest Bank Minnesota.

11:00 am – Noon, Thursday, December 4, 2008

More than any industry, railroads have made Kansas City a regional metropolis. The story of railroading in this area is a richly human one, populated by important and visionary figures like Octave Chanute, Fred Harvey, and Arthur Stilwell.The industry continues to thrive today, thanks largely to its inherent fuel efficiency, making railroads a green option for the 21st century. But how – and where – did the train industry begin in Kansas City? Today Steve Kraske talks with Peter Hansen, editor of Railroad History, the academic journal of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society. They’ll discuss how railroads impacted Kansas City – how trains permanently changed the land, and the way that people and goods traveled over it. We’ll also talk with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art executive director Marc WilsonArt in the Age of Steam: Europe, America and the Railway, 1830-1960 about the museum’s special exhibit of . The exhibit, on display through January 18th, features more than 100 paintings, prints, drawings and photographs drawn from 64 museums and private collections.

Art in the Age of Steam is the most wide-ranging exhibition ever assembled of American and European works of art responding to the drama of the railroad, from the earliest days when steam trains churned across the landscape through the romance of the Victorian era to the end of the steam era in the 1960s.

Peter A. Hansen is the editor of Railroad History, the academic journal of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, and his work also appears frequently in Trains and Classic Trains magazines. His next Trains cover story will appear in the February 2009 issue. Titled The Rail Splitter and the Railroads, it was done at the behest of the Lincoln Bicentennial Commission in honor of the 16th president’s 200th birthday. Pete was a contributor to the Encyclopedia of North American Railroads, published by

Peter A. Hansen is the editor of Railroad History, the academic journal of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, and his work also appears frequently in Trains and Classic Trains magazines. His next Trains cover story will appear in the February 2009 issue. Titled The Rail Splitter and the Railroads, it was done at the behest of the Lincoln Bicentennial Commission in honor of the 16th president’s 200th birthday. Pete was a contributor to the Encyclopedia of North American Railroads, published by  the Indiana University Press. He is currently research assistant to Bill Withuhn, the transportation curator at the Smithsonian Institution, on an engineering study of American steam locomotive technology.

the Indiana University Press. He is currently research assistant to Bill Withuhn, the transportation curator at the Smithsonian Institution, on an engineering study of American steam locomotive technology.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

For more information about the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art’s exhibit Art in the Age of Steam click here.

On Slavery 9 – Partus Sequitur Ventrem

When considering slaves, Colonial Virginians abandoned the English tradition of partus sequitur patrem (one’s status was determined by the disposition of their father) in favor of the Roman principle of partus sequitur ventrem, a “child inherits the condition of the mother.” (1) Thus offspring of slave women were the property of their mother’s owner whether fathered by freeman or not. Annette Gordon–Reed, in her book “The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family,” speculates on why Virginian colonists made up this particular form of slavery that endured until the Civil War.

“White men, particularly the ones who made up the House of Burgesses, the legislature in colonial Virginia, were the masters of a growing numbers of African women, owning not only their labor but their very bodies. That these women sometimes would be used for sex as well as work must have occurred to the burgesses. Inevitably offspring would arise from some of these unions. Even white males who owned no slaves could contribute to the problem by producing, with enslaved black women, children who would be born free, thus destroying a critical component of the master’s property right: the ability to capture the value of the “increase” when female slaves gave birth.” (2)

Gordon-Reed goes on to describe an actual court case that occurred in 1655 in which Elizabeth Key, a woman of mixed blood, “successfully sued for her freedom on the basis of the fact that her father was English.” (3) This ruling, if left to stand as precedent, would have created a gap by which a growing number of children could escape slavery, those fathered by free white men and black women in bondage.

The impacts were staggering. First, the law “assured that white men – particularly the privileged ones who passed the law, who would not likely have been hauled into court for fornication even with white women – could have sex with enslaved women, produce children who were items of capital, and never have to worry about losing their property rights in them.” (4)

Gordon-Reed suggests that the law was likely intended to reduce racial-mixing in that along with it was passed a measure that increased the fines for mixed-race couples that engaged in sex out of wedlock. But in effect, it meant “the private conduct of men would have no serious impact on the emerging slave society as a whole. White men could engage in sex with black women without creating a class of freeborn mixed-race people to complicate matters.” (5)

Second, the law implied that every person suspected of having African blood, was assumed to be a slave unless they could prove otherwise. “…The English common-law presumption in favor of freedom did not apply to Negroes; in all slave states (except Delaware) the presumption was that people with black skins were slaves unless they could prove that they were free.” (6) Kenneth Stampp explains that this hyper race sensitive system required that “the offspring of a free white father and a Negro, mulatto (half), quadroon (one Negro grandparent), or octoroon (one Negro great-grandparent) slave mother was a slave.” (7) This ruling once again encouraged exploitation of women in that mixed-blood, often very white appearing women, were kept as slave prostitutes to service white men.

Paradoxically, the child of a black enslaved father and a free white mother was considered by law in most states, free. Likewise, children found to have descended from a female Indian were considered free because, with the exception of a short time in the 17th century, it was unlawful to enslave an Indian.

Paradoxically, the child of a black enslaved father and a free white mother was considered by law in most states, free. Likewise, children found to have descended from a female Indian were considered free because, with the exception of a short time in the 17th century, it was unlawful to enslave an Indian.

As might be imagined, interpretation of the rules governing race and thus one’s status as property varied by locale. “In Alabama a ‘mulatto’ was ‘a person of mixed blood, descended, on the part of the mother or father, from negro ancestors, to the third generation inclusive, though one ancestor of each generation may have been a white person.” (8) South Carolina didn’t specifically define terms such as Negro and mulatto but left interpretation to visible evidence of mixture and took into account “a person’s reputation among his neighbors.” (9) One was considered free in Kentucky if it could be proven that one had “less than a fourth of African blood.” (10)

The legacy of the men who created a country built upon laws that supported racial slavery was in part the creation of a culture that expended a great deal of energy establishing the racial status and thus property rights to a growing population of mix-blood “chattel personal.” It was a legacy that encouraged widespread abuses and the flagrant misuse of female slaves who had no legal rights at all. As contended by Gordon-Reed, “under the rules of the game the burgesses constructed,” there was no need to interfere with other men’s conduct. Whatever the social tensions and confusion created by the presence of people who were neither black nor white, Virginia’s law on inheriting status through the mother effectively ended threats to slave masters’ property rights when interracial sex produced children who confounded the supposedly fixed categories of race.” (11) Hyper-race sensitivity and all its implications would continue for centuries to come.

For more information on Elizabeth Key’s freedom case, see a paper by Taunya Lovell Banks from the University of Maryland School of Law, “Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key’s Freedom Suit – Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth Century Colonial Virginia” here.

(1) Kenneth M. Stamp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South, (New York: Vintage Books, 1956), 193.

(2) Annette Gordon – Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008), 46.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Ibid., 46-47.

(6) Kenneth M. Stamp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South, 193-194.

(7) Ibid., 194.

(8) Ibid., 195.

(9) Ibid.

(10) Ibid., 196.

(11) Annette Gordon – Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, 47.

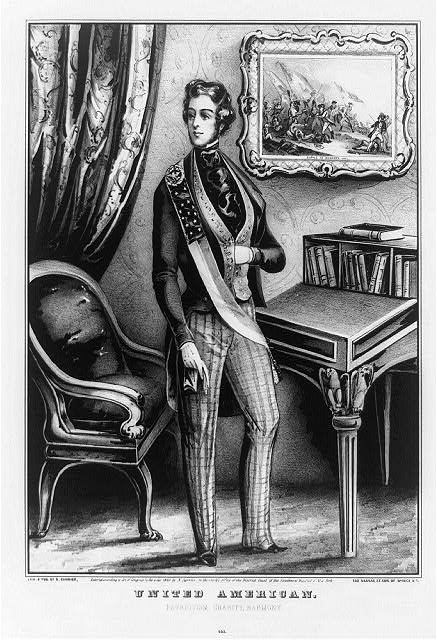

In the spring of 1850, another nativist fraternity, The Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB) was founded in New York City by Charles B. Allen, a thirty-four-year-old commercial agent born and educated in Massachusetts. (1) At first a simple “local fellowship numbering no more than three dozen men, there was little to distinguish their order from many other ‘patriotic’ groups, little reason for anyone to expect that it would be the core of a major political party, the greatest achievement of nativism in America.” (1) By 1852, it began to grow quickly and leaders of the Order of United Americans (OUA) took notice. Many of their membership joined and the OSSB membership swelled “from under fifty to a thousand in three months.” (1) Later that year, the two organizations joined under the leadership of James Barker and, with astute organizational skill, hundreds of lodges were formed “all over the country with an estimated membership ranging up to a million or more.” (2) Those who joined promised, as a part of secret rituals, to “vote for no one except native-born Protestants for public office” and “the Order endorsed certain candidates or nominated its own” in secret councils. Because their rules required them to say they “knew nothing” about the organization if asked, the movement became known as the “Know Nothings” (3)

In the spring of 1850, another nativist fraternity, The Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB) was founded in New York City by Charles B. Allen, a thirty-four-year-old commercial agent born and educated in Massachusetts. (1) At first a simple “local fellowship numbering no more than three dozen men, there was little to distinguish their order from many other ‘patriotic’ groups, little reason for anyone to expect that it would be the core of a major political party, the greatest achievement of nativism in America.” (1) By 1852, it began to grow quickly and leaders of the Order of United Americans (OUA) took notice. Many of their membership joined and the OSSB membership swelled “from under fifty to a thousand in three months.” (1) Later that year, the two organizations joined under the leadership of James Barker and, with astute organizational skill, hundreds of lodges were formed “all over the country with an estimated membership ranging up to a million or more.” (2) Those who joined promised, as a part of secret rituals, to “vote for no one except native-born Protestants for public office” and “the Order endorsed certain candidates or nominated its own” in secret councils. Because their rules required them to say they “knew nothing” about the organization if asked, the movement became known as the “Know Nothings” (3)

Bits of white paper strewn across a prearranged site announced the meeting of the brotherhood. Held at night, in keeping with the secrecy that shrouded its early years, the sessions of the local chapters of the Order of the Star Spangled Banner were open only to initiates and those about to join them in the ranks. The ritual for admission to the lodge seemed endless. But instead of irritating men tired after a long day’s work, the elaborate raps and special handclasps, the passwords between brothers, and the sentinels sent to escort candidates long known to the membership seemed to heighten the feeling of camaraderie, the sense of special excitement at the dangerous but essential mission they were privileged to share. For they were there to save and cleanse the nation, to preserve for themselves that abstraction which some would later call the American dream.

Bits of white paper strewn across a prearranged site announced the meeting of the brotherhood. Held at night, in keeping with the secrecy that shrouded its early years, the sessions of the local chapters of the Order of the Star Spangled Banner were open only to initiates and those about to join them in the ranks. The ritual for admission to the lodge seemed endless. But instead of irritating men tired after a long day’s work, the elaborate raps and special handclasps, the passwords between brothers, and the sentinels sent to escort candidates long known to the membership seemed to heighten the feeling of camaraderie, the sense of special excitement at the dangerous but essential mission they were privileged to share. For they were there to save and cleanse the nation, to preserve for themselves that abstraction which some would later call the American dream.