Posts Tagged ‘Antebellum America’

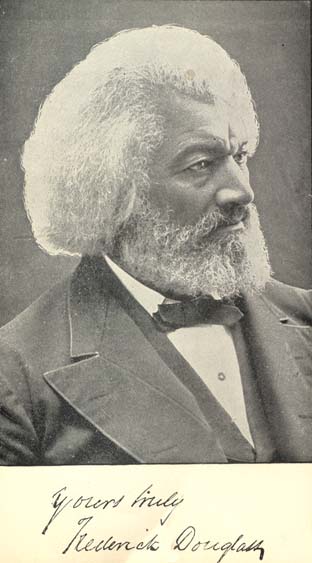

Freeaudio.com Carries the Works of Douglass, Lincoln, and Others

In this world of hustle and bustle, having books read to me is a wonderful luxury. Today I found a terrific site, Freeaudio.org, that takes largely public domain works and provides them free to the public in audio form. This trumps my Kindle 2 text-to-speech feature in that real human readers are easier to listen to.

I picked up the American Library version of Frederick Douglass’ works back in January and love it, but with freeaudio.org, I can clean the garage and “listen” to a professional reading of Douglass’ work as performed by Marvin Pain, an excellent reader.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave Part 1

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave Part 2

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave Part 3

I will be adding the site to my “Primary Sources” links. Note that some of Abraham Lincoln’s speeches are also available.

I plan on submitting a donation and asking that they begin putting up some of the biographies and autobiographies of our American Civil War military men as well as soldiers diaries.

Frederick Douglass

Next Term’s Books are In! Mostly…

Ah the thrill of the sound of book boxes being dropped on my front porch and then the doorbell ringing. Nothing like it!!

One of two Amazon boxes delivered today.

Just over half of my books arrived today for next term’s class, Civil War Strategy and Tactics. See related post here.

I had to put them on my bookcase where I won’t open them until after finals. Too much to do before the term ends. Torture.

Apologies for short post. Know you’ll understand. Two papers due by Sunday and need to read the last two chapters of Holt.

The Compromise of 1850: Effective Political Action or Forecast of Disaster?

Thanks to everyone that has participated in the Compromise of 1850 Poll going on here. If you haven’t voted, please do!

To expand the discussion, let me share my perspective on the question I raised, whether The Compromise of 1850 was an effective political action or a forecast of disaster.

The United States Senate, A.D. 1850. Drawn by P. F. Rothermel; engraved by R. Whitechurch. c1855. Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Number: LC-USZCN4-149

Michael F. Holt makes an excellent case in his classic, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s , that the Compromise of 1850 was more a forecast of disaster than effective political action. His argument is founded on the premise that the Compromise was effectively a deathblow to the Second American Party System and the notion that the health of America’s political parties in the mid-19th century was crucial to containment of sectional strife. As long as “men had placed their loyalty to their own party and defeat of the opposing party within their own section ahead of sectional loyalty, neither the North nor the South could be united into a phalanx against the other.” (1)

This conclusion is, of course, more easily arrived at when looking back at the period through the lens of generations with the full knowledge that the country would be ripped apart within fifteen years in a tumultuous Civil War. The perspectives of the politicians who negotiated the Compromise of 1850 would have, at the time, been much different. Indeed, they might have seen it as artful politics. The agreements made in the Compromise appeared to solve, at least temporarily, the country’s major ills which – on the surface – revolved around slavery and the country’s expansion.

But the effect was the displacement of the country’s trust in “party” as voice and defender of political views. The void caused men to affiliate more with their section, North and South. The scene was set for the country’s festering issues to rise again to a boil, this time without the benefit of cross-sectional parties that had so successfully contained discord in the past.

Thus my conclusion is that the Compromise of 1850 was BOTH an effective political action AND a forecast of disaster. It was effective for a time in that it allowed the country to continue forward with at least a fragile agreement on monumental issues. But its destruction of the Second American Party System led the country toward potential destruction.

And so…. what do you think? Comments welcome.

—-

See images of the original document – The Compromise of 1850 here.

(1) Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s, (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1983), 139.

The Invention of Party Politics Requires a Page of Its Own

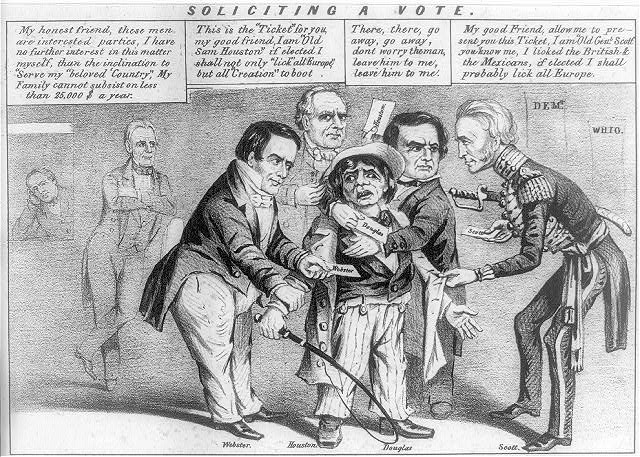

"Soliciting a Vote" Probably drawn by John L. Magee. Source: RN: LC-USZ62-14075 Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/p.print

Studying Antebellum America, as I’m doing this term, provides a fascinating look at the development of the notion of “political parties.” Keeping track of all of the political groups in Antebellum America has become a challenge. I need a list or a matrix. That said, I’ve decided to build a new page called “The Political Groups.” The only content so far is as follows but I’ll be adding over time.

Federalists, Silver Grays, Whigs, Democrats, Free Soil Party, Unionists, Liberty Party, Know Nothings (American Party), American Republicans, Anti-Masonic

To all of my readers, your input on information, books, and links to good sites with information on 19th century political groups before, during, and after the American Civil War will all be enthusiastically received. The list above should not be in any way construed as complete. State as well as national parties are game.

By the way, there is an interesting book I’ve run across on the subject, The Invention of Party Politics: Federalism, Popular Sovereignty, and Constitutional Development in Jacksonian Illinois, by Gerald Leonard, University of North Carolina Press, 2002. 328 pgs. I’ve quoted Mr. Leonard in at least one of my posts this term: On Slavery, Sectionalism, and the First and Second Party Systems here.

To house this an other books on the topic, I’ve added a page titled Political Groups to my virtual bookshelves here. I’ve remapped some of the books on the Antebellum America shelf to this one as well since the topics overlap.

Leonard provides an outstanding list of books and articles on this topic in his bibliography. Some I own including both of Holt’s books: The Political Crisis of the 1850’s and The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party, and thanks to reader elektratig, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s, by Tyler G. Anbinder 9See earlier post on Anbinder’s book here). Others, I’d like to obtain. I may load the entire bibliography to my virtual bookshelves over time as reference and have started that effort here. It’s a long and fantastic list so will take some time.

About the Image: “A cynical view of party competition for the working man’s vote in the presidential campaign of 1852. In a polling place, four candidates struggle to force their own election ticket on a short, uncouth-looking character in a long coat. The latter holds a whip, suggesting that he is either a New York cabman or a farmer. The candidates are (left to right): Whig senator from Massachusetts Daniel Webster, Texas Democrat Sam Houston, Illinois Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, and Whig general Winfield Scott. The cartoon must have been produced before the June 5 nomination of dark-horse Franklin Pierce as the Democratic candidate, as Pierce is not shown. Webster: “My honest friend, these men are interested parties, I have no further interest in this matter myself, than the inclination to ‘Serve my beloved Country,’ My Family cannot subsist on less than 25,000 $ a year.” His comment may refer to his own personal financial straits or to the nepotism involved in securing his son Fletcher’s lucrative appointment as surveyor of the Port of Boston in 1850. Scott (in uniform, grasping the man’s coat): “My good Friend, allow me to present you this Ticket, I am ‘Old Genl. Scott’ you know me, I licked the British & the Mexicans, if elected I shall probably lick all Europe.” Houston: “This is the ‘Ticket’ for you, my good friend, I am ‘Old Sam Houston’ if elected I shall not only ‘lick all of Europe,’ but all ‘Creation’ to boot.” Douglas (his arms around the man): “There, there, go away, go away, don’t worry the man, leave him to me, leave him to me.” Affixed to the wall at right are two posters or signs marked “DEMT.” and “WHIG.” In the left background stands Henry Clay leaning against a chair observing the scene, along with President Millard Fillmore who looks in through a window.”

Quoted from the Library of Congress.

On Slavery, Sectionalism, and the First and Second Party Systems

Alexander Hamilton (Source: Wikicommons, public domain)

The “First Party System,” according to Donald Grier Stephenson, pitted the Federalists (created by Alexander Hamilton and including John Adams, Fisher Ames, and John Marshall) against the Republicans or Antifederalists (created by Thomas Jefferson and including James Madison, Albert Gallatin, and Philip Freneau) and “took shape at the national level soon after government under the Constitution got under way in 1789.” (1) Gerald Leonard points out that the Constitution was, by design, against parties, and so these first party-like-organizations were not “mass-based” but existed “more as parties in the government than as parties in the electorate.” (2) They were, in effect, political cliques.

“In supporting or opposing policy proposals in Congress, members found themselves increasingly voting with the same group of colleagues on one side of an issue or the other. In turn, members sought reelection by defending their positions on legislation and so carried to the electorate the disputes that had divided Congress. Partisanship thus filtered down to the voters, leading them to associate one kind of policies with one group and different policies with another. The result was that congressional factions acquired local followings that duplicated congressional divisions.” (3)

Until the early 19th century, the first party system focused on the issues surrounding political and economic structure. Federalists favored centralization and a strong national government that was more closed and elitist-based. They pushed for an active economic policy. Republicans championed more dominant state governments, openness, and thus less elitism.

Thomas Jefferson

With the election of Thomas Jefferson as president in 1800, Republicans replaced the Federalists as the dominant party. Jefferson expanded the powers of the president, reasserted a focus on states rights and agrarianism, and expanded the nation with the Louisiana Purchase. The Federalists gradually faded away as a credible political force and by 1820 could offer no candidate for the presidency. “Rivalry among Republican leaders for the presidency and the reemergence of major national policy issues marked the end of the first party system between 1810 and the mid-1820s.”(4) The years between I8I6 and I824 saw a regression of sorts toward anti-partyism and the period “lacked major national issues of the intensity that had earlier sparked partisan combat. The period thus came to be called the ʻEra of Good Feeling.’”(5)

But economic developments in the 1820s caused a resurgence of interest among the populace in politics as they sought to influence their own circumstances through control of government. Southern fears of anti-slavery sentiments surged as the debate around the fate of Missouri’s statehood galvanized many to take interest in the polls. Grass roots political energy began to emerge indicating a clear deathblow to The First Party System, which pushed policy from government down to the populace. This would no longer do.

Historian Michael Holt, who approaches the questions surrounding causation of the American Civil War from the angle of politics, posits that what makes a democratic republic like the United States work is a political structure that allows for discord on issues to be managed as a part of debate among varying points of view. (6) Constructive debate works best when there exist at least two political parties with elected officials who can, at the national, state, and local level, wrangle with the issues and make decisions that direct civic direction. Citizens can align with the party that best represents their perspective and interests. Choice between party platforms provides opportunity for change via regular elections.

A single party system does not facilitate competition between ideas. In fact, Holt suggests that the lack of a two party system can cause people to align around other identifiers such as the region in which they live. “Sectional antagonism was most marked, powerful, and dangerous precisely at those times when or in those places where two-party competition did not exist.” (7) By contrast, these “sharp section lines often disappeared” when two parties were present effectively diffusing sectional antagonism. “When it persisted, party loyalties neutralized it so far as shaping political behavior. As many politicians recognized, in short, inter-party competition was an alternative to naked sectional conflict.” (8)

Martin Van Buren Credit: Former President Martin Van Buren, half-length portrait, facing right. Photographed between 1840 and 1862, printed later. LC-USZ62-13008 DLC. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. By Popular Demand: Portraits of the Presidents and First Ladies, 1789-Present.

Thus the ebb and flow in the severity of sectional conflict in America can be traced to the relative competitive strength or weakness of a two-party system. Holt suggests that two strong parties did not exist in the years between 1819 and 1821 when the decision of whether Missouri would be admitted to the union as a slave or free state was being considered. Sectional strife resulted. To prevent the sectional strife from fully permeating politics, “Martin Van Buren helped form the Jacksonian Democratic party in the 1820’s specifically to revive a two-party system as a substitute for sectionalism. (9) The intent was to counteract feelings of sectional prejudices by encouraging party alignment. In this way, issues surrounding slavery contributed to the reemergence of strong parties, and thus “The Second American Party System.” As the Second Party System emerged between 1824 and 1828, the Democratic-Republican Party split into the Jacksonian faction, which became the modern Democratic Party in the 1830s, and the Henry Clay faction, which was absorbed by Clay’s Whig Party. Unlike the era of “The First American Party System,” this period saw mass-based parties that could mobilize the electorate. Voters could thus feel empowered to effect change through suffrage. Sectionalism and thus many of the critical questions surrounding slavery were, once again, contained within the boundaries of political debate, at least for a time.

—-

(1) Donald Grier Stephenson, Campaigns and the Court: The U.S. Supreme Court in Presidential Elections (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 27, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=111837005.

(2) Gerald Leonard, The Invention of Party Politics: Federalism, Popular Sovereignty, and Constitutional Development in Jacksonian Illinois (University of North Carolina Press, 2002)

(3) Stephenson, Campaigns and the Court: The U.S. Supreme Court in Presidential Elections, 27.

(4) Ibid., 28.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850s ( New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983).

(7) Ibid., 6.

(8) Ibid., 6 – 7.

(9) Ibid., 7.

New Acquisition – Fredrerick Douglass Autobiographies

My study of Antebellum America this term has revealed a significant gap in my library. That has been filled with the arrival this week of Frederick Douglass: Autobiographies. I purchased The Library of America edition. I like the look and feel.

It includes three works:

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

- My Bondage and My Freedom

- Life and Times of Frederick Douglass

From historian Bruce Levine,

“Frederick Douglass’s magnificent autobiography, The Life and Time of Frederick Douglass is indispensable.”

I look forward to getting to know this important American.

Bruce Levine, Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of Civil War, Revised (Hill and Wang: New York, 2005), 264.

New Acquisition: Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings & the Politics of the 1850’s

My copy of Tyler Anbinder’s Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings & the Politics of the 1850’s finally arrived yesterday. One of my readers recommended it as one of the best resources on the Know Nothings Party which I’ve just finished a series of posts on. Can’t wait to dig in.

ISBN13: 9780195089226

ISBN10: 0195089227

Paper, 352 pages

Oxford University Press

Published: May, 1994

Winner of the Avery O. Craven Award of the Organization of American Historians

New York Times 1992 Notable Book of the Year

Chosen by The Gustavus Myers Center as a 1992 Outstanding Book on Human Rights in the United States Outstanding Book on Human Rights

Dr. Anbinder is chair of the Department of History at The George Washington University. You can view his complete C.V. here.

Dr. Anbinder is chair of the Department of History at The George Washington University. You can view his complete C.V. here.

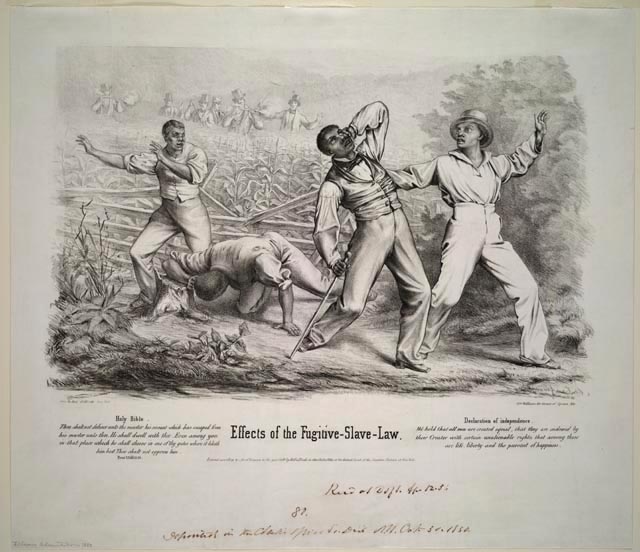

Fugitive Slave Law Backfires

Source: American Treasurers of the Library of Congress

Interesting reading from Bruce Levine’s text, Half Slave and Half Free : The Roots of Civil War, this evening. He contends that the fugitive slave law that was a part of the Compromise of 1850 actually did more damage to slavery’s cause than good.

So long as slavery seemed geographically contained and remote, free-state residents could despise it without feeling much direct personal involvement in its workings; slavery could thus remain the peculiar institution of the South, not a problem or responsibility of the North. By sending slave hunters into the free states and requiring even antislavery citizens to aid them, however, the new law made such rationalizations impossible.

Net-net: pushing compliance to slavery controls “compelled Northerners to confront slavery as a national, not just a sectional, issue.” (Levine, 189-190)

About the image:

S. M Africanus

The Fugitive Slave Law

Hartford, Connecticut: 1850

Printed broadside

Rare Book & Special Collections Division (33A)

In 1850, Congress passed this controversial law, which allowed slave-hunters to seize alleged fugitive slaves without due process of law and prohibited anyone from aiding escaped fugitives or obstructing their recovery. The law threatened the safety of all blacks, slave and free, and forced many Northerners to become more defiant in their support of fugitives. Both broadside and print, shown here, present objections in prose and verse to justify noncompliance with this law.

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 7

Fight between the Rioters in Kennsington. Source: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. From: "A Full and Complete Account of the Late Awful Riots in Philadelphia." Philadelphia: John B. Perry, 1844.

Social historian David H. Bennett provides an in-depth view of the Know Nothing Party’s origins and attempts to get at the reasons for its emergence in his outstanding book, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement. He points to the incredible social upheaval occurring in America in the mid-19th century. Drawing from analysis of the way that people deal with change, Bennett points to the growing sense of a loss of control over personal destiny experienced by many native born American men, the complete antithesis of the self-deterministic opportunities upon which the nation was formed. The result was xenophobia, the target those who were not native born and the largest immigrant groups by the 1850’s were Irish and German.

Immigrants proved the perfect target for many Americans in these troubled times. They could associate their own loss of power or status with the emergence of a subversive group disrupting time-honored relationships. In a social order threatened by catastrophe, polarization between the forces of good and evil satisfied the desire for enemies on whom to pin the blame, whose defeat could restore the stability of the cherished past.

(1) David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement , (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 107.

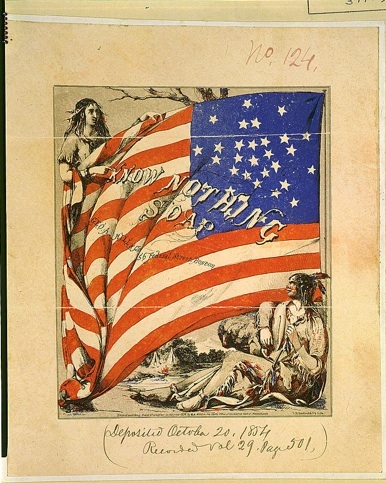

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 6

Know-Nothing Soap, Library of Congress, Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

With the election of 1854, a stunning demonstration of the Know Nothings’ magnetic appeal, nativism became a new American rage.

Know Nothing candy, Know Nothing tea, and Know Nothing toothpicks were marketed, buses and stagecoaches received the charmed name, the clipper ship Know Nothing was launched in New York. Books appeared with “KN” on the cover, “Know Nothing” poems found easy publication, and the widely circulated Know Nothing Almanac or True American’s Manual was issued. The Almanac had schedules for sunset and moon phases mixed with a potpourri of nativist polemics, including stories of Catholic machinations in Ireland, statistics of foreigners in the almshouses and charity hospitals, as well as warnings of every kind of alien conspiracy. (1)

What had humble beginnings, as a fraternity, was now the American party. “Those in the movement remained proud of the secret order at the heart of the political organization.” (1)

——

(1) David H. Bennett, The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History, 115.

About the image: An illustrated advertising label for soap manufactured in Boston, interesting for its imagery and allusion to the popular “Know Nothing” or nativist movement. In the foreground are two American Indians, emblematic of the movement’s prejudice against the foreign-born. In the lower right is a seated brave, leaning against a rock and holding a pipe. Above him a large American flag, with thirty-one stars, unfurls across the main picture area. The flag is supported in the upper left corner by an Indian woman, who points to the words “Know Nothing Soap” emblazoned on it. In the background is a landscape with tepees and a campfire on the bank of a stream.

Medium: 1 print : lithograph printed in red, grey, blue, and black on coated paper ; 15.2 x 12.6 cm. (image)

Created/Published:1854.

Great Post on the Origins of Know Nothings

Elektratig, one of my favorite blogs on Antebellum American history, has a post worth reading on the origins of the name “Know Nothing” that you can read here. Recommended reading for those following my series on Know Nothings and/or Antebellum America.

Political History Word of the Day – Jingoistic

I ran across the word “jingoistic” tonight in my reading of a fascinating book, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement by David H. Bennett.

I ran across the word “jingoistic” tonight in my reading of a fascinating book, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement by David H. Bennett.

jingoistic

adjective

fanatically patriotic [syn: chauvinistic]

jin·go·ism

Extreme nationalism characterized especially by a belligerent foreign policy; chauvinistic patriotism.

jin’go·ist n., jin’go·is’tic adj., jin’go·is’ti·cal·ly adv.

Here is a snippet from Bennett’s book to show the context of his use of the word.

The greatest upheaval was the clash between the North and South. The issue of slavery, and the sectional conflict it helped to generate and exacerbate, was inextricably connected to territorial expansion. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 temporarily resolved that issue, setting the famous line (36° 30″) to the Pacific, north of which the South’s “peculiar institution” could not be extended. But the question flared anew with the Mexican War and the prospect of a rich California territory and a new estate in the desert and mountain West available for American settlement and development. This war of expansion did not unify the country as have international conflicts in some tranquil times. Nor did that other jingoistic outburst against the British in the debate over division of the Oregon territory in the far Northwest. (2)

(1) jingoistic. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/jingoistic (accessed: December 20, 2008)

(2) David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement [book on-line] (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988, accessed 20 December 2008), 95; available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=105437276; Internet.

On Slavery – 6 Chattels Personal

Kenneth Stampp’s chapter “Chattels Personal” is excellent. I suspect that “chattel” is not a word most of us learn unless we study law or Antebellum American history in depth. Its meaning in the context of slavery is, of course, that person’s slaves were consider legally as “chattel personal.”

Being a person quite taken with words, I did a little research on the origins of this one and found it informative. Interestingly, a search for the etymology of the word found some disagreement. The following perspective comes from French: A Linguistic Introduction.

“Chattel comes from the French noun cheptel used to designate all movable property, but now is restricted to ‘livestock’. English has gone a step further: cattle used to designate any movable property, then all livestock, and now is generally restricted to bovines. English also has the word chattel, legally any type of movable property, but more specifically in modern usage, it refers to slaves. All of these terms are ultimately derived from the Latin word capitalis, which has been reintroduced in modern financial vocabulary, e.g. capital campaign in fundraising. This term, in turn, is derived from the Latin word caput, ‘head’ (French chef), with the result that ‘head of cattle’, our original example, ultimately is a ‘head of things with heads’!” [1]

This from A New Law Dictionary and Glossary…

“…the singular chattel seems to be immediately formed from the Fr. chatelle, or chatel, (q.v.); the plural chattels, (or, as it was formerly written, catals,) is supposed to be derived from the L. Lat., catalla, the ch being pronounced hard, as in the word charta, which is evident from the form of the old Norman plural, cateux, (q.v.). As to any further derivation, catalla or catalia is clearly shown by Spelman to be merely a contracted form of writing capitalia, which with the singular capitale, or captale, occurs frequently in the Saxon and early English laws. The primary meaning of capitalia was animals, beasts of husbandry, (otherwise call averia, q.v.) or cattle; in which last word it is still identically retained.

Capitalia is derived by Spelman from capita, heads; a term still popularly applied to beasts, as “so many “heads of cattle.” When the word took the form catalla, it continued to retain this primary meaning, but gradually acquired the secondary sense of movables of any kind, inanimate as well as animate, and finally became used to signify interests in lands.”

CHATTELS PERSONAL, otherwise called THINGS PERSONAL, comprise all sorts of things movable, as good, plate, money, jewels, implements of war, garments, animals and vegetable productions; as the frit or other part of a plant, when severed from the body of it, or the whole plant itself, when severed from th ground. Besides things moveable, they include also certain incorporeal rights or interestes, growing out of, or incident to them, such as patent rights and copyrights…” [2]

——

[1] French: A Linguistic Introduction

By Zsuzsanna Fagyal, Douglas Kibbee, Fred Jenkins

Published by Cambridge University Press, 2006

ISBN 0521821444, 9780521821445

337 pages (pp. 154-155), Accessed online, November 16, 2008, http://books.google.com/books?id=4yTA6SvGuekC&pg=PP1&dq=French:+A+Linguistic+Introduction#PPA154,M1

[2] A New Law Dictionary and Glossary

By Alexander M. Burrill

Published by The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 1998

ISBN 1886363323, 9781886363328

1099 pages (pp. 207-208), Accessed online, November 16, 2008, http://books.google.com/books?id=DeQYXYMBtwgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=etemology+of+the+word+chattel#PPA208,M1

Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South.

On Slavery – 5 Escaping

Historian Kenneth Stampp makes an interesting point about differing locations of slaves determining the destination of escapees. Those living near Indians might, for example, seek refuge with local tribes, as was the case in Florida.

“…Florida slaves escaped to the Seminole Indians, aided them in their wars against the whites, and accompanied them when they moved to the West. At Key West, in 1858, a dozen slaves stole a small boat and successfully navigated it to freedom in the Bahamas. Arkansas runaways often tried to make their way to the Indian country.” (Stampp, 120)

Those nearer to the north often choose to escape to the north where there was a greater presence of abolitionists.

Those in Texas would escape in larger numbers to Mexico.

“In Mexico the fugitives generally were welcomed and protected and in some cases sympathetic peons guided them in their flight.” (Stampp, 120)

Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South

On Slavery – 1

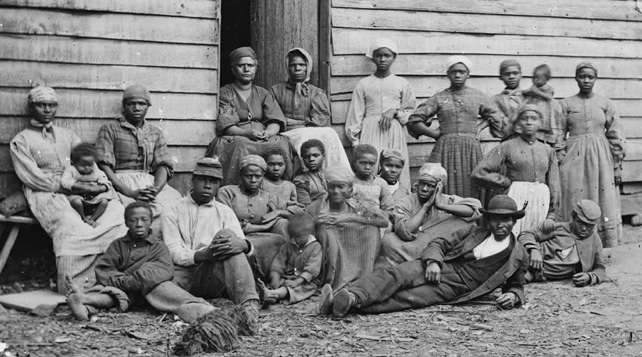

Photograph of Slave Cabin and Occupants Near Eufala, Barbour County, Alabama (Photo source: Library of Congress)

I’m reading Kenneth M. Stampp’s fascinating book, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South for class. A focus this week and next is, among other things, the ways in which slave owners controlled their bondsmen. The methods varied considerably as did the ethical sensibilities of the masters and overseers. Stampp suggests that behavioral control included both the carrot and the stick with heavy weighting on the stick. That is to say, some masters and/or overseers used positive incentives and some negative.

Positive incentives included: work stoppage at noon on Saturdays and Sunday off, holidays off, parties and dances, holiday gifts, cash for the best worker for a given period, the right to grow one’s own crops whether for personal food or sale, the right to rent oneself out and keep some of the income, and the ultimate incentive, the right to achieve freedom.

Negative incentives were many. Stampp suggests that few adult slaves did not have some experience with flogging. This seemed to be the most acceptable method of disciplining slaves and was used extensively. Other forms of physical punishment used to control slaves included: confinement either in “the blocks” or even jail, mutilation (ranging from castration to branding), and even more severe forms of torture. For young slaves or those who needed “breaking,” there were actually specialists who through, undoubtedly mental and physical persuasion, reduced high spirited individuals to more pliable and subservient workers.

Another method of control was the introduction of religion to the slaves. Indoctrination of slaves into Christianity had its advantages. It was not uncommon for them to ensure that sermons emphasized those verses in the Bible that instructed servants to obey their masters. (Stampp, 158) Particular focus was made on teaching slave children “respect and obedience to their superiors” in the belief that it made them better servants. (Stampp, 159) This suggests a fascinating area of study – the effects of religion on American slaves – for which I must look for information. Let me know if you can recommend any.

And so we watch history being made…

It’s poignant that I’ve started a course this week that examines antebellum America – a country of profound inequality and bigotry. If you are an American, regardless of who you voted for, I hope you celebrate the process of democracy that we shared in together today. And marvel at the incredible journey that this country has made to this important day.

What a transformational moment in history…

What a time to be a student of history…

Howe Wins 2008 Pulitizer Prize for History

Daniel Walker Howe’s (right) 2007 book, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1818-1848, has won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for History. It is a part of the Oxford History of the United States series. The citation can be read here. I have not read the book yet but plan to. Appreciate any feedback from those of you who may have already read it.

Daniel Walker Howe’s (right) 2007 book, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1818-1848, has won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for History. It is a part of the Oxford History of the United States series. The citation can be read here. I have not read the book yet but plan to. Appreciate any feedback from those of you who may have already read it.

What Hath God Wrought

The Transformation of America, 1815-1848

Daniel Walker Howe

ISBN13: 9780195078947

Hardback, Sep 2007

Price: $35.00

photo credit: Julie Franken

In the spring of 1850, another nativist fraternity, The Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB) was founded in New York City by Charles B. Allen, a thirty-four-year-old commercial agent born and educated in Massachusetts. (1) At first a simple “local fellowship numbering no more than three dozen men, there was little to distinguish their order from many other ‘patriotic’ groups, little reason for anyone to expect that it would be the core of a major political party, the greatest achievement of nativism in America.” (1) By 1852, it began to grow quickly and leaders of the Order of United Americans (OUA) took notice. Many of their membership joined and the OSSB membership swelled “from under fifty to a thousand in three months.” (1) Later that year, the two organizations joined under the leadership of James Barker and, with astute organizational skill, hundreds of lodges were formed “all over the country with an estimated membership ranging up to a million or more.” (2) Those who joined promised, as a part of secret rituals, to “vote for no one except native-born Protestants for public office” and “the Order endorsed certain candidates or nominated its own” in secret councils. Because their rules required them to say they “knew nothing” about the organization if asked, the movement became known as the “Know Nothings” (3)

In the spring of 1850, another nativist fraternity, The Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB) was founded in New York City by Charles B. Allen, a thirty-four-year-old commercial agent born and educated in Massachusetts. (1) At first a simple “local fellowship numbering no more than three dozen men, there was little to distinguish their order from many other ‘patriotic’ groups, little reason for anyone to expect that it would be the core of a major political party, the greatest achievement of nativism in America.” (1) By 1852, it began to grow quickly and leaders of the Order of United Americans (OUA) took notice. Many of their membership joined and the OSSB membership swelled “from under fifty to a thousand in three months.” (1) Later that year, the two organizations joined under the leadership of James Barker and, with astute organizational skill, hundreds of lodges were formed “all over the country with an estimated membership ranging up to a million or more.” (2) Those who joined promised, as a part of secret rituals, to “vote for no one except native-born Protestants for public office” and “the Order endorsed certain candidates or nominated its own” in secret councils. Because their rules required them to say they “knew nothing” about the organization if asked, the movement became known as the “Know Nothings” (3)