Archive for the ‘The American Civil War’ Category

Civil War High Tech: Excavating the Hunley and Monitor from MIT World

Always on the hunt for opportunities to inform my understanding of history, I’ve hit a gold mine. In addition to my fascination with the Civil War, I am equally passionate about maritime history and am a degreed engineer. Those three fields of study converge in a fascinating symposium hosted by the DeepArch Research Group in Technology, Archaeology and the Deep Sea at MIT in April 2003 which they have made available for viewing on MIT Earth (TM).

The symposium, Civil War High Tech: Excavating the Hunley and Monitor gives us an opportunity to hear from the senior archaeologist on the recovery of the C.S.S. Hunley, Maria Jacobsen. For those of you familiar with Civil War Naval history, the CSS Hunley will not be a new name. For those not, its story is nothing less than remarkable. A Confederate submarine, it was lost after driving a mine into the hull of USS Housatonic, detonating it, and sending the ship to the silty bottom of Charleston Bay in five minutes. But the Hunley was lost as well, only to be found, recovered, and excavated in the last decade or so.

I have made it through the first presentation on the Hunley (wow) and hope to watch the second half of the symposium on the Monitor. But for now, this from the MIT site:

Civil War High Tech: Excavating the Hunley and Monitor

- Moderator: Merritt Roe Smith

- Maria Jacobsen

David A. Mindell PhD ’96

Brendan Foley PhD ’03

About the Lecture

In the last few years, archaeologists have recovered two of the Civil War’s most ingenious inventions: the Union ironclad warship Monitor and the Confederate submarine Hunley. In this symposium panelists discuss the newest technology projects that have brought these inventions to light from the sea depths, and what they can teach about technology and the Civil War.

Submarine CSS H. L. Hunley [1863-1864]

- Submarine built by Horace L Hunley

- First submarine to destroy an enemy ship

- All three crews died aboard although several from the first crew were able to escape.

- Lost off of Charleston after sinking the USS Housatonic with a spar torpedo

- Remains discovered in 1995 by NUMA

- Recovered August 8, 2000

Photo credit: Confederate Submarine H.L. Hunley (1863-1864) U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph [#NH999]

You may be interested in previous posts I’ve made on the Hunley. My first was the following:

On Dog Tags, Sunken Confederate Subs, and Graves Registration

Lincoln and His Admirals

I’m very pleased to have received a review copy yesterday of Lincoln and His Admirals by Craig L. Symonds from the terrific folks over at Oxford University Press. You can view the book’s listing at OUP here. Being a student of both the American Civil War AND maritime history, I can’t think of a better read. I’m reserving this one for the Christmas holiday. This will also be my first introduction to the work of Craig L. Symonds. More to come on my review.

Hardcover: 448 pages

Publisher: Oxford University Press, USA (October 17, 2008)

ISBN-10: 0195310225

ISBN-13: 978-0195310221

Dimensions: 9.2 x 6.3 x 1.5 inches

On Slavery – 2

Continuing from On Slavery – 1 here.

Marie Jenkins Schwartz in her OAH Magazine of History article, “Family Life in the Slave Quarters: Survival Strategies,” points out that slave masters attempted to control slave children by disrupting the normal authority they might feel towards their parents.

Marie Jenkins Schwartz in her OAH Magazine of History article, “Family Life in the Slave Quarters: Survival Strategies,” points out that slave masters attempted to control slave children by disrupting the normal authority they might feel towards their parents.

“Masters and mistresses considered the slave’s most important relationship to be that maintained with an owner. They worried that children reared to respect other authority figures, such as parents, might question the legitimacy of the southern social order, which granted slaveholders sweeping power over the people they held in bondage. Consequently, owners planned activities and established rules intended to minimize the importance of a slave’s family life and to emphasize the owner’s place as the head of the plantation.”

Schwartz further suggests that a number of slave owners referred to their slaves a family members and though not treated as such, this helped in their self–justification of exercising full power and control over every aspect of a slave’s life.

Civil War Blog Addition and British History Online

I’ve made some additional adds to my blogroll and links. First a belated welcome to Jim Beeghley whose blog, “Teaching the Civil War with Technology” has not only a strong premise but some terrific posts.

Welcome Jim! http://blog.teachthecivilwar.com

And thanks to Alex Rose over at The History Man blog for a lead to British History Online. This is an impressive site with some great information including primary sources. I’ve added it under a new category titled History Sites of Merit.

New Arrival – Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief

This week I received a review copy of James M. McPherson’s new work, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief from the good folks at Penguin Press. Needless to say, I’m very much looking forward to diving in as Dr. McPherson’s books on Lincoln remain among my favorites.

He opens the book with the following.

“The insurgent leader…does not attempt to deceive us. He affords us no excuse to deceive ourselves. He can not voluntarily reaccept the Union; we can not voluntarily yield it. Between him and us the issue is distinct, simple, and inflexible. It is an issue which can only be tried by war and decided by victory.”

—Lincoln’s annual message to Congress,

December 6, 1864

Tried by War

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief

James M. McPherson – Author

Hardcover | 6.14 x 9.25in | 384 pages | ISBN 9781594201912 | 07 Oct 2008 | The Penguin Press

Next Class: Antebellum America: Prelude to Civil War

After a short break, I’ll be diving into my next class which starts November 3rd. As is my custom, I’ve added this to “The Courses” page.

“Antebellum America: Prelude to Civil War” (starts November 3rd)

This course is an analysis of the conditions existing in the United States in the first half of the 19th century. The course focuses on the political, cultural/social, economic, security, leadership, and other issues that played roles in starting and shaping the Civil War. We will analyze the issues in the context of war and peace to determine whether or not such conflicts as civil wars can be avoided prior to their inception.

Required Texts:

TBD once the syllabus is available. For now, the list is as follows which is very light in comparison with my last class:

Publisher: W. W. Norton and Company

Publisher: W. W. Norton and CompanyHalf Slave and Half Free : The Roots of Civil War by Bruce Levine

Road to Disunion : Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854, Volume 1 by William W. Freehling

New Addition – Sweetsmoke by David Fuller

I received a review copy of David Fuller’s Sweetsmoke today from the good folks at Hyperion and very much look forward to reading it and passing along my impressions. Mr. Fuller is a screenwriter by profession. He has an interesting lineage of combatants in the American Civil War, which you can read more about on his website here.

The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare

Edward Hagerman. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. Reprint. Indiana University Press, 1992.

In this important work on tactical and strategic military history, Edward Hagerman posits that the American Civil War marshaled in a new era in land warfare colored by the impacts of the Industrial Revolution. He argues that the complete command and control systems of armies was impacted by factors both occurring across the globe (i.e. technological developments in weaponry and transportation) and unique to America: its culture, geography, and history.

In this important work on tactical and strategic military history, Edward Hagerman posits that the American Civil War marshaled in a new era in land warfare colored by the impacts of the Industrial Revolution. He argues that the complete command and control systems of armies was impacted by factors both occurring across the globe (i.e. technological developments in weaponry and transportation) and unique to America: its culture, geography, and history.

Hagerman is clear in setting two broad aims for the book. The first is to provide a new analysis of the “theory, doctrine, and practice of field fortification in the tactical evolution of trench warfare.” The second is to analyze the development of field transportation and supply and its impact of the movement and maneuvering of Civil War armies

Hagerman organizes his study around several themes. The first addresses the ideas and education that informed the American military including the influence of theorists such as Jomini, Clausewitz, and at West Point, Dennis Hart Mahan. Secondly he looks at the organizational change, or lack thereof, in the Army of the Potomac including an explanation of the educational orientation of its leaders. Thirdly he explores the Army of Northern Virginia and the culture and traditions which informed men of the south who entered the military. Next he dives into the emergence of trench warfare and the strategic and tactical evolution that resulted from it. And importantly, he finishes with the evolution of total war and the strategy of exhaustion.

This work should be of particular interest to military historians and even more so to those interested in the American Civil War and its impact on military logistics, the use of technology, weaponology, military tactical and strategic thought, and the concepts of modern warfare and its history.

There is an extensive notes section valuable to the serious student of military history. This is augmented by a “Works Cited” section including listings of primary sources. The introduction to the book provides an exceptional summary of many of the key factors that impacted the war.

Edward Hagerman brings to this study the credentials of academician. He was Associate Professor of History at York University in Toronto, Canada at the time of the book’s publication. He is also the recipient of the Moncado Prize of the Society of Military History.

Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea

Belatedly, I want to mention that I’ve received a pre-publication copy of Noah Andre Trudeau’s Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea, which I’ll hope to provide a full review of before too long. At first blush, it appears to be an excellent read.

Since this book falls into the category of Civil War Campaigns, I’ve added a shelf in my virtual bookstore to accommodate it which you can find here.

As a student of military history, one of the many things that I find so fascinating about Sherman’s march is that its destructive power encourages its consideration as “total war” a la Clausewitz. Can’t wait to dig in to this one.

For those of you in the Chicago area, Mr. Trudeau’s publisher Harper Collins, indicates that he will be publicizing his book at the following on Thursdays.

05:00 PM – 07:30 PM

PRITZKER MILITARY LIBRARY

2nd FL 610 N Fairbanks Court Chicago, IL 60611

Baltimore Sun’s Civil War Books Discussion

Dave Rosenthal, the Sunday and Readership Editor for the Baltimore Sun, asked me to contribute to a discussion of Civil War Books on their book blog, Read Street. I’m up for any opportunity to talk about books. Check out my recommendations and those of fellow commentators here.

Technology in U.S. Military History – 1

My current course on Studies in U. S. Military History (see courses page here) is drawing to a close. We have been examining the last of Millett and Maslowski’s major themes which is that “the United States has used increasingly sophisticated technology to overcome logistical limitations and to match enemy numbers with firepower.” [i] I find this supportable in the sense that it has been possible to see a steady progression of technological prowess over time. Nowhere, arguably, have technological advancements been felt more than in the arena of weaponry.

Professor of history Alex Roland (Duke University) posits that “before the twentieth century, most soldiers and sailors ended their careers armed as they were at the beginning. New weapons were introduced slowly, if at all, and most professionals resisted the uncertainties new arms introduced.” But, Roland asserts, “by the second half of the twentieth century, this traditional suspicion of new weapons had changed to a reckless enthusiasm.” The phenomena of obsolescence on introduction entered the national psyche in that, by the time many “weapons entered service, their successors were being planned. This was especially true in large-scale weapons systems such as ships and aircraft. It even found its way into thinking about less complex military technologies, such as radios and computers.” [ii]

More in Part 2. Note I provide a link below to Professor Roland’s excellent article titled “Technology and War” which can be read online.

[i] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, xiii.

[ii] Alex Roland, “Technology and War,” http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/AD_Issues/amdipl_4/roland2.html Accessed 13 July 2008.

Coggins’ Arms and Equipment of the Civil War

I’m a fan of Jack Coggins. An author and illustrator, Coggins has captured some golden nuggets of information in his book, Arms and Equipment of the Civil War. He has also written and illustrated a number of other mlitary history books no doubt influenced by his tour of duty as illustrator for YANK magazine during World War II. Members of Coggins extended family have put up a website (quite well done) by way of tribute to Jack. You can reach it here.

Military History Word of the Day: Enfilade

From a letter by Private Mathew A. Dunn of Company C, 33rd Mississippi Infantry Regiment, to his wife shortly after the Battle of Peachtree Creek.

“Our Reg. suffered worse than any other, being on the flank and was exposed to an enfilading fire. We lost our Col. He charged waving his Sword until he fell.”

Battle of Peachtree Creek

Source: Wikipedia Commons

The following are definitions from several sources.

en·fi·lade

(ěn’fə-lād’, -läd’)

n.

- Gunfire directed along the length of a target, such as a column of troops.

- A target vulnerable to sweeping gunfire.

tr.v. en·fi·lad·ed, en·fi·lad·ing, en·fi·lades

To rake with gunfire.

[French, series, string, row, from enfiler, to string together, run through, from Old French : en-, in, on; see en-1 + fil, thread (from Latin fīlum; see gwhī- in Indo-European roots).]

Source: enfilade. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/enfilade [accessed: July 06, 2008].

—-

enfilade

1706, from F. enfilade, from O.Fr. enfiler “to thread (a needle) on a string, pierce from end to end,” from en- “put on” + fil “thread.” Used of rows of apartments and lines of trees before modern military sense came to predominate.

Source: enfilade. Dictionary.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/enfilade [accessed: July 06, 2008].

—–

Enfilade

En`fi*lade”\ (?; 277), n. [F., fr. enfiler to thread, go through a street or square, rake with shot; pref. en- (L. in) + fil thread. 1. A line or straight passage, or the position of that which lies in a straight line. [R.] 2. (Mil.) A firing in the direction of the length of a trench, or a line of parapet or troops, etc.; a raking fire.

Source: enfilade. Dictionary.com. Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary. MICRA, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/enfilade [accessed: July 06, 2008]

New American Civil War Forum Blog

I was visiting TOCWOC today and noticed mention of a new Civil War blog. It hasn’t been that long ago that I was the new kid so knowing how much I appreciated the mentions on fellow blog sites am passing along the goodwill. Please take a moment to visit The American Civil War Forum Blog here. I will be adding to my blogroll momentarily.

Two Brothers: One North, One South

While on vacation, I received a review copy of David H. Jones’ Two Brothers: One North, One South.

This has moved very quickly up to the top of my reading stack for between terms. It is an aesthetically beautiful book. And I’m impressed by the weaving of fact into the story. I’m also hooked by the notion that poet Walt Whitman is the story’s glue. Can’t wait and more to come once I can put my feet up on the porch and enjoy.

By the way, Mr. Jones maintains a website here and a blog here which carries the same title as his book but covers more information. I’m adding it to my blogroll as I rather like the information and really do enjoy following the blogs or historical authors.

Product Details

- Hardcover: 320 pages

- Publisher:Staghorn Press; First edition [February 1, 2008]

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 0979689856

- ISBN-13: 978-0979689857

- Product Dimensions: 9.1 x 6 x 1.3 inches

- Shipping Weight: 1.2 pounds

Professional Military Reading List Links Added

Please note that I’m in process of adding more links to the right nav bar under the heading of “Reading Lists.” Collected here are professional military reading lists and those associated with universities in military history. These lists are really quite interesting and range from the classical works of military theorists to the latest in business leadership. If you find a list I don’t have noted, please let me know.

Civil War Railroad Page Updated

By way of housekeeping, I’ve updated the Popular Series Posts page on the right nav bar titled Civil War Railroads here with the latest series of posts titled “Stewards of Civil War Railroads.”

Above: United States Military Railroad 4-4-0 locomotive W.H. Whiton (built by William Mason in 1862) in January 1865 with Abraham Lincoln’s presidential car, which later was used as his funeral car.

Source: Wikicommons

May Civil War and Military History Book Acquisitions – II

Continuing with my May book acquisitions which illustrate, as said by Civil War Interactive’s comments on my blog this week, why bank robbery may be needed to support my book-buying habits…

This looks like a great read. Author Tom Wheeler, an accomplished man by any measure, has a terrific website here with more about his book and research. This has moved to the top of my list of reading for between terms.

I have DISCOVERED Dr. Hess and the growing list of terrific titles he has published on the Civil War. No doubt his other books will show up in my library before long. Dr. Hess, who has impressive academic credentials, has a website here. His book, Pickett’s Charge: The Last Attack at Gettysburg, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

I’ve been intending to pick this up. Authored by military history professor and fellow blogger Mark Grimsley, it too is at the top of my reading list. Dr. Grimsley’s OSU webpage is here. His blog is here.

My post, “Fabian Strategy and the American Civil War” here, lead me to this book. One of my readers recommended it and suggests that it proves that the Confederacy could not have used the Fabian strategy effectively. I’m looking forward to this one.

Jav Luvaas is another prolific writer of military history and my collection of his books is growing. I first discovered his work while taking the course, Great Military Philosopers (see “The Courses” page here for details. I picked up his titles: Napoleon on the Art of War and Frederick the Great on the Art of War.

I’ll be adding these authors to my “The Historians” page shortly.

May Civil War and Military History Book Acquisitions – I

Catching up on acquisitions of new books in May. I’ve really got to get on a book budget.

Note that I’ve added two new category pages to my vitural bookshelves here. These include:

Military History

I’ve added serveral recommended military history reference books.

Encyclopedia of American Military History (3 beautiful volumes!)

The War Companions Set: Consisting of The Oxford Companion to American Military History and The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern War 2-Volume Set

From Oxford University Press, USA

The Reader’s Companion to Military History

By Society for Military History

An Encyclopedia of Battles: Accounts of Over 1,560 Battles from 1479 B.C. to the Present

By David Eggenberger

War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History: 1500 to Today

By Max Boot

The Savage Wars Of Peace: Small Wars And The Rise Of American Power

By Max Boot

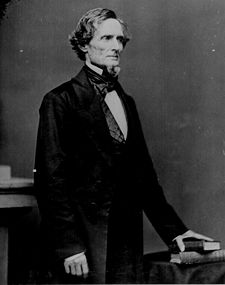

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part II Davis

This post continues from Part I, here.

Jefferson Davis (above) and the Confederate Congress, by contrast, were reluctant to wrestle control of the railroads away from civilian owners. This was consistent with a laissez faire pattern exhibited by Davis on a number of issues involving civilian commercial interests and may have been a response to the populace’s opposition to overbearing centralized government. The consequences were dire for Lee. In the winter of 1862, he found his Army of Northern Virginia completely reliant on its communications. [i]

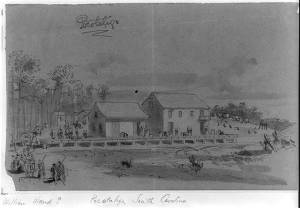

Above: Pocotaligo, South Carolina – Railroad depot center of image surrounded by rough sketch of soldiers and covered wagons. Circa: 1865

Medium: 1 drawing on tan paper : pencil, black ink wash, and Chinese white ; 14.7 x 21.4 cm. (sheet).

Source: Library of Congress Ref: LC-USZ62-14306 (b&w film copy neg.)

With the mobility, indeed the survival, of the army dependent on the efficient use of the railroads, the railroad owners responded with an assertion of their individual rights. They failed to cooperate. Government shipments were accorded low priority. The railroads over which the animals’ feed had to be transported refused to use the space for bulk fodder. The breakdown of the railroad system led to a crisis in the supply of horses, mules, fodder, and subsistence. The Army of Northern Virginia was left hanging at the end of its lines of communications.[ii]

Above: Warrenton Depot, on the Orange & Alexandria RR, in August 1862. Supply point for Lee.

Davis’ refusal to give greater control to the military for operation of the railroads added to “the weight of this burden of waging war by improvisation within the confines of the Confederacy’s social and political ideals [and] helped break the back of Confederate offensive power.” [iii]

Edward Hagerman notes that problems continued into 1863 as “conflicts between the commissary agents of field commanders and those of the [Confederate] Subsistence Department hampered efficient gathering of available resources.” [iv] The largest obstacle was “the failure of the railroads to cooperate in the distribution of food surpluses from other states to the Army of Northern Virginia. Neither the army nor the government exercised any control over the railroads.” [v] It wasn’t until Lee’s army was faced with starvation that the Confederate Congress intervened. In April of 1863, it “hesitantly” granted Jefferson Davis the “authority to regulate the railroads.” [vi]

The laissez faire-minded Davis was as reluctant to accept the authority as the Confederate Congress was to bestow it. Here was the instrument to prevent a recurrence of the crisis of the past winter. It would enable through scheduling the interchange of rolling stock from one railroad to another. It also would enable the War Department, rather than the railroad owners, to decide on the priority of material to be transported. [vii]

Davis signed the bill into law but Congress ensured its ineffectiveness by failing to approve an “office of railroad superintendent” as proposed by the secretary of war and by sacking the temporary appointee. [viii] “Not until early 1865, far too late, did the Confederacy finally take control of the railroads.” [ix]

[i, ii, iii] Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 121.

[iv, v] Ibid., 130.

[vi, vii, viii] Ibid., 131.

[ix] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, 165.

New Page: the weapons… first entry – Minié ball

I am in need of another page on which to collect notes about weapons. I’ve begun it here. First entry…

I am in need of another page on which to collect notes about weapons. I’ve begun it here. First entry…

Cylindroconcoidal Bullet [“Minié ball”]

- Invented by a Captain Norton of the British army in 1832. [TACWOMW, 16]

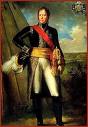

- Perfected by Claude-Etienne Minié (right) in 1843, a captain in the French army. [TACWOMW, 16]

“Previously too slow to load, the rifle became a practical weapon on the battlefield. The Minie ball could be dropped down the muzzle of a rifle almost as easily as if it were round. T he net result was additional range, velocity, and accuracy.” [TACWOMW, 16]

Photo: Minié Ball design from Harpers Ferry. Source; Wiki commons.

————-

[TACWOMW] – Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988).

Mahan’s Elementary Treatise

WOW! I am absolutely engrossed in Edward Hagerman’s The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. So much to say about Dennis Mahan (right) who I wrote about briefly here in my series on Jomini on the Nature of War (Part VII – Jomini’s Impact on Civil War Leadership). The National Park Service has a good bio on Mahan here.

WOW! I am absolutely engrossed in Edward Hagerman’s The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. So much to say about Dennis Mahan (right) who I wrote about briefly here in my series on Jomini on the Nature of War (Part VII – Jomini’s Impact on Civil War Leadership). The National Park Service has a good bio on Mahan here.

I was very pleased to find online Mahan’s Elementary Treatise on Advance-Guard, Out-Post, and Detachment Service of Troops (1847) which Hagerman references in detail. This text was developed by Mahan for West Point and is considered the first tactics and strategy text created for the United States. I’ll add this to my primary sources links on Wig-Wags.

I can tell already that I’ll have many terms to add to the terms page. More to come of the French connection.

And so…The American Civil War

We ha ve arrived in “Studies in U.S. Military History” (see course information here) at the American Civil War. We’ll spend two weeks on this war, more than any other. Millett and Maslowski’s For the Common Defense splits the war into two periods: chapter six, 1861 – 1862 and chapter se

ve arrived in “Studies in U.S. Military History” (see course information here) at the American Civil War. We’ll spend two weeks on this war, more than any other. Millett and Maslowski’s For the Common Defense splits the war into two periods: chapter six, 1861 – 1862 and chapter se ven, 1863-1865. It is chock full of interesting statistics, enough to begin to fill a “page” on the blog where I can keep them handy. And so, yet another new page: the statistics.

ven, 1863-1865. It is chock full of interesting statistics, enough to begin to fill a “page” on the blog where I can keep them handy. And so, yet another new page: the statistics.

Next, a book I’ve already done a little reading in but am very much looking forward to, Edward Hagerman’s The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. This does not strike me as a fast read which is fine. I’m glad we can give it a solid two weeks.

And so a few statistics from Millett and Maslowski – always fascinating for this student of mathematics and engineering.

- 1861 White Male Population: North – 20 million; South – 6 million

- 800,000 immigrants arrived in the North, betwee 1861 adn 1865, including a high proportion of males liable for military service

- 20 – 25 percent of the Union Army was foreign-born

- 2 million men served in the Union Army

- 750,000 men fought in the Confederate Army which was a maximum strenght in late 1863 with 464,500

- Not all of these men on either side were “present for duty.” Out of the 464,500 Confederates, only 233,500 were “present for duty.”

- Taxation produced less than 5% of the Confederacy’s income. It produced 21% of Union government income.

- The Confederacy printed $1.5 billion in paper money, the Union $450 million in “greenbacks.”

- In 1860, the nothern states had 110,000 manufacturing establishments, the southern states, 18,000.

- During the year ending June 1, 1860, the states forming the Confederacy produced 36,790 tons of pig iron. The state of Pennsylvania alone produced 580,049 tons.

- The South contained 9,000 miles of railroad track to the North’s 30,000 miles.

- 100,000 Southern Unionists fought for the North with every Confederate state except South Carolina providing at least a battalion of white soldiers for the Union Army. Millett and Maslowski call these the “missing” Southern Army and “a crucial element in the ultimate Confederate defeat.

—–

Source: Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 163-167.

Sobering Numbers

As I was finishing up my reading on the American Revolution this evening, I learned the following regarding the percentage of the American population killed in several of our wars.

1st place: Civil War – 1.6 % of population killed

2nd place: American Revolution – 1.0 % of population killed

By contrast, 0.06 % of Americans met their demise in the Mexican War, 0.12 % in World War I, and 0.28 % in World War II.

Indeed sobering.

——

Source: Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America, (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 82.

Jomini on the Nature of War – Part II – The Burgeoning Military Theorist

This post continues from Part I here. Please note links in blue lead to additional information on those topics.

Antoine-Henri Jomini (below right) was born on March 6, 1779 in the small town of Payerne (Payerne church pictured right) in western Switzerland. His family was an old and influential one; his father Benjamin active in local politics. Jomini grew up with the French Revolution and the sight of French soldiers was something he was familiar with even as a boy. He was a teenager working in banking in Paris when the Swiss Revolution of 1798 broke out, largely instigated by the French at the proding of exiled Swiss radicals. Jomini’s father joined the revolutionary cause and served in various political roles in the Helvetian Republic. Antoine-Henri caught the fever of revolution as well and returned home where, at the age of nineteen, he became the secretary to the Swiss minister of war. He attained military rank (captain) and a reputation for being bright, diligent, and full of ambition. By

Antoine-Henri Jomini (below right) was born on March 6, 1779 in the small town of Payerne (Payerne church pictured right) in western Switzerland. His family was an old and influential one; his father Benjamin active in local politics. Jomini grew up with the French Revolution and the sight of French soldiers was something he was familiar with even as a boy. He was a teenager working in banking in Paris when the Swiss Revolution of 1798 broke out, largely instigated by the French at the proding of exiled Swiss radicals. Jomini’s father joined the revolutionary cause and served in various political roles in the Helvetian Republic. Antoine-Henri caught the fever of revolution as well and returned home where, at the age of nineteen, he became the secretary to the Swiss minister of war. He attained military rank (captain) and a reputation for being bright, diligent, and full of ambition. By twenty-one, he had command of a battalion. [i]

twenty-one, he had command of a battalion. [i]

It was during this time that he began a vigorous study of military history. John Shy suggests that Jomini was…

“obsessed by visions of military glory, with himself imitating the incredible rise of Bonaparte (below right) who was only ten years his senior, but in a telling phrase Jomini remembers being possessed, even then, by “le sentiment des principes” — the Platonic faith that reality lies beneath the superficial chaos

of the historical moment in enduring and invariable principles, like those of gravitation and probability. To grasp those principle, as well as to satisfy the more primitive emotional needs of ambition and youthful impatience, was what impelled him to the study of war. Voracious reading of military history and theorizing from it would reveal the secret of French victory.” [ii]

The Luneville Treaty of 1801 (see exerpts here) ended the Napoleonic Wars and Jomini returned to Paris where he maintained a devotion to the study and writing of military theory. He had been enthralled by Napoleon’s leadership. It is beyond disptue that the French had achieved a breakthrough in warfare and Jomini was about trying to find out how they had done it.

“Answering this question, persuasively and influentially, would be Jomini’s great achievement. The wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon generated a vast, receptive audience for the

kind of clear, simple, reassuring explanation that he would offer. Drawing overtly on the prestige of ‘science’ and yet almost religious in its insistent evangelical appeal to timeless verities, Jomini’s answer to this troubling question seemed to dispel the confusion and allay much of the fear created by French military victories.” [iii]

By 1804, Jomini had completed his Traité des grandes opérations militaires (Treastise on Great Milita ry Operations). He managed to ingratiate himself to General Michel Ney (right), leader of Bonaparte’s Sixth Corps, who had served for a time as French viceroy in Switzerland. Ney helped him to publish this first book. It would find its way to Napoleon and Jomini’s life would be forever changed. [iv]

ry Operations). He managed to ingratiate himself to General Michel Ney (right), leader of Bonaparte’s Sixth Corps, who had served for a time as French viceroy in Switzerland. Ney helped him to publish this first book. It would find its way to Napoleon and Jomini’s life would be forever changed. [iv]

Jomini’s principles would also find their way to West Point in the years preceeding the American Civil War. In Part III, I’ll discuss what those principles were.

[i] Hugh Chisholm, The Encyclopedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. 11th Ed, Volume XV. (Cambridge, England: At the University Press, 1911), 495. Accessed online 2/23/2008: here.

[ii, iii, iv] John Shy, “Jomini,” in Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 144 – 149.

Photos: Public Domain – Wiki Commons

This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War

Pamela Cortland at Alfred A. Knopf Publishing (an imprint of the Knopf Publishing Group at Random House) has given me the opportunity to review on Wig Wags what looks like a fascinating book. I should have it in hand by early next week but wanted to go ahead and make a quick comment.

Format: Hardcover, 368 pages

On Sale: January 8, 2008

Price: $27.95

ISBN: 978-0-375-40404-7 (0-375-40404-X)

This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust is a study of how the country came to terms with the 620,000 deaths that resulted from the Civil War. Given my recent posts on death and injury on the battlefield (see here and here), the topic is of considerable interest to me.

It is almost inconceivable to think of losing that many of our countrymen and women today in the cause of any war. The impact at the personal level – among both those who died and those who loved them – is one measure of the war’s magnitude. Another is the enormity of the logistics of dealing with that much death.

The book’s author, Drew Gilpin Faust, holds the Lincoln Professorship of History at Harvard University and was, oh by the way, installed as its president a few months ago as well. You can read more about President Faust here.

She authored five previous books, including Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War, which won the Francis Parkman Prize awarded by the Society of American Historians and the Avery Craven Prize. I’ll be adding President Faust to my “the historians” Page.

More on the book later.

HOW THE SOUTH Could Have Won the Civil War

Today I received for review a copy of HOW THE SOUTH Could Have Won the Civil War: The Fatal Errors That Led to Confereate Defeat. Author Bevin Alexander claims to destroy the myth of the inevitability of a Union victory. I plan to read it with open mind.

I haven’t yet determined where to place this book on my virtual bookshelves so for now, it’s filed on shelf three of “Civil War Era and Commentary.”

More to come.

ISBN 978-0-307-34599-8

The Crown Publishering Group (a division of Random House)

Were the North and South Evenly Matched…on the Rails?

One of the questions that was much debated in class was whether the North and South were evenly matched in the American Civil War? To get the discussion rolling, our professor threw out the following…

In his interesting study of the American Civil War, Archer Jones argues in Civil War Command and Strategy: The Process of Victory and Defeat (1992), that despite its superior numbers, the Union advantage was greatly diminished by the extent of Southern territory, the intrinsic superiority of the defense over the offense, and the problems of supplying armies over long distances. Jones also states that Northern industrial dominance also proved almost useless in a war that depended less on complex weaponry and ammunition than on the man with the rifle. In Jones’ opinion, the two sides were, in fact, almost evenly matched.[i]

Our task was to take a stand on whether the North and South were evenly matched. I decided to focus on the very specific area of railroad transportation during the war. Part of my interest in this area comes from my association with friend and rail historian Peter A. Hansen, the editor of Railroad History and author of a number of articles for Trains Magazine. I was able to interview him on the topic and have included a good part of that in the post below. The photo below will be included in the upcoming issue of Railroad History which “is given over to a nearly-encyclopedic overview of every company that ever built steam locomotives in America.”[ii] The principal contributor is John H. White, Jr., former curator of transportation at the Smithsonian Institution.

Photo: New Jersey Locomotive & Machine-built 4-4-0 Fred Leach near Union Mills, Va., on August 1, 1863, the year after it was built. Its stack and tender have taken cannon shot, and the main rod is missing. It became Orange and Alexandria Warrenton after the American Civil War. Library of Congress: 111-B-185.

Charles Roland, in his book An American Illiad: The Story of the Civil War, provides a strong case for the American Civil War being considered the “first complete railroad war.” He asserted that the North was well ahead of the South in railroad resources entering into the war with 20,000 miles of rails in 1860 to the South’s 10,000. The railroads of the north were better “linked into systems of trunk lines that covered the entire region.”[iii] There were other things that made the North’s railroads superior. “First, it was dotted with locomotive factories, concentrated particularly in Massachusetts, Paterson, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. All of them remained beyond the reach of Rebel forces, so production was never disrupted. It was never disrupted for want of materials, either, since most of the iron ore and coal were also concentrated in the North.”[iv]

“In addition, the North’s railroads were almost all built to the standard track gauge of 4’ 8 ½”. That meant the cars could be interchanged from one line to another without the need for time-consuming unloading and reloading of passengers and freight. In the South, the rail network was pretty thin to begin with, and the multiplicity of track gauges hampered operations even more. That was particularly important considering that most of the war was fought on Southern soil. With the notable exception of one shining moment at the First Battle of Bull Run, the South was never consistently able to rush men and materiel to the front by rail. There were just too many obstacles to such smooth operation in most of Dixie.”[v]

Photo above: Station at Hanover Junction, Pa., showing an engine and cars. In November 1863 Lincoln had to change trains at this point to dedicate the Gettysburg Battlefield. LOC: 111-B- 83.

Photo below: The four-tiered, 780-foot-long railroad trestle bridge built by Federal engineers at Whiteside, Tenn., 1864. A guard camp is also shown. Photographed by George N. Barnard. LOC: 111-B-482.

“It’s a little-known fact, but track gauge was the first big standardization issue – in any industry. It seems incredible to us from our modern perspective, but many people were slow to grasp the need for standardization. It had never been needed in the days when every village had its own blacksmith or carpenter, whose products never needed to be used in conjunction with those of the smithy or carpenter in the next town.”[vi]

Photo above: Tredegar Iron Works. Artist: Alexander Gardener, Public Domain, Wikipedia Commons.

“The South didn’t have a single locomotive factory of any consequence during the Civil War. Several had made a start during the 1840s and 1850s but failed to survive into the War years – including Richmond’s famous Tredegar Iron Works (see the American Civil War Center’s site at Tredegar Iron Works here). While the firm itself survived until 1956, they produced locomotives only from 1851 to 1860. Even as the storm clouds were gathering, they decided in late 1860 that the locomotive business wasn’t profitable for them, and they retooled the shop for other uses.

“[vii]

Photo right (cropped): James Noble Sr. from www.civilwarartillery.com/manufacturers.htm.

“Aside from Tredegar, the only wartime Southern locomotive factory that’s even marginally worth mentioning was James Noble and Son of Rome, Georgia. They produced only a few locomotives after 1855 and their factory was destroyed by Sherman’s army in 1864. What this means, of course, is that Southern railroads became increasingly dysfunctional as their locomotives were destroyed, since they had no means of replacing them. It also meant that their remaining locomotives were often old, and/or held together by any means possible.”[viii]

McPherson substantiates this in his book, Battle Cry of Freedom. He indicates that of the 470 locomotives built in the U.S. in 1860; only 19 were built in the South.[ix] According to Hansen, “the production of 470 locomotives in a single year may seem like a large number. But it is less surprising in light of two things. First, railroad mileage in the U.S. had surpassed 30,000, and about 2/3 of that total had been built in the previous decade. Just like new highways today, there was comparatively little traffic on new lines in their first couple of years, but usage mushroomed when people and businesses began to change their previous transportation preferences, and when businesses began to locate along the new lines. When a line began to see more traffic, whether two or five or eight years after it was built, new locomotives were needed to handle it. An economist might say that the need for rolling stock lagged the actual construction by a few years.”[x]

“Another thing to consider is the poor utilization of assets in those days. Just as standardization was a new concept in the middle of the 19th century, so, too, was asset utilization. The latter concept is quite recent indeed, not being fully understood until just the past decade or so. [Note: Consider that Southwest Airlines ran circles around its competitors for years, chiefly because SWA insisted on having an entire fleet of identical planes, and on keeping them on the ground for only 30 minutes at each stop. The underlying rationale for both policies was better asset utilization. The older airlines are still struggling to apply those same lessons.] A steam engine is a highly labor-intensive beast. It requires constant attention from fireman and engineer alike in order to get maximum productivity while it’s working, and it spends about two hours in the shop for every hour it spends on the road. That time is absolutely necessary to the proper functioning of the machine, since grates need to be shaken, ashes need to be dumped, and moving parts need lubrication. (Tallow was a common valve lubricant in those days before petroleum engineering, and applications had to be repeated frequently.) About once a month, the steam engine’s fire was dumped altogether so the tubes and flues could be inspected. The process of cooling an engine down, inspecting it, and firing it back up typically took 24-48 hours, so there’s a big chunk of unproductive time right there. So the bottom line is that they needed a lot of locomotives in those days!”[xi]

Brilliant Uses of Railroads

The South did have some success with the use of trains for troop transfer. Johnston’s use of the Manassas Gap Railroad to move his troops to Manassas Junction to reinforce Beauregard was brilliant and no doubt influenced the outcome of that engagement which so demoralized the North. Roland also reviews Bragg’s “almost incredible strategic use of the railroads” against Buell as the latter approached Chattanooga. “The Confederates half-circled the Union army by moving 30,000 from Tupelo, Mississippi, roundabout by way of Mobile and Atlanta to Chattanooga, a movement of some 776 miles.”[xii] Hansen felt that, “while it was true that Bragg’s campaign was a remarkable success in the face of daunting logistics, this was the exception that proves the rule.” The mere fact that he had to detour 776 miles in order to go 300 speaks to the paucity of railroads in the South. And even in his 776-mile detour, he had to port his troops on foot east of Montgomery, where the railroad ended, before he could load them on trains again near Columbus, Georgia. So yes, the railroads helped him win, but I submit that it was his audacity, combined with Buell’s dithering, that gave him the ability to make the best of a questionable asset.”[xiii]

Hansen added, that “it is worth noting that railroads were the whole reason Chattanooga had such strategic significance. The principal line from Richmond to Atlanta, and the line from Memphis to the east, converged there. Without Chattanooga, the South’s ability to move men and materiel by rail in their own territory was all but gone.”[xiv]

Thomas Ziek, Jr. came to the same general conclusion in his Master’s Thesis, “The Effects of Southern Railroads on Interior Lines during the Civil War.” He tried to determine whether or not the South enjoyed the advantage of interior lines and concluded that they did not.

The use of railroads during this conflict placed an enormous physical strain upon the limited industrial resources of the Confederacy, and a great strain upon the intellectual agility of the Confederate High Command. Based upon the evidence studied, and the time-space comparisons of both Northern and Southern railway operations, several conclusions can be drawn: the South entered the war with a rail system that was unable to meet the demands of modern war; the Confederate leadership understood the importance of the railroad and its importance to strategic operations early in the war, but were unwilling to adopt a course of action that best utilized their scarce assets; Union control, maintenance, and organization of its railway assets ensured that it would be able to move large numbers of troops at the strategic level efficiently from early 1863 to the end of the war. Based on these conclusions, the Confederacy lost the ability to shift troops on the strategic level more rapidly than the Union by 1863. This was a result of its physically weakened railroad system and military setbacks which caused Southern railroads to move forces over longer distances.[xv]

My conclusion, for this area of focus, is that the North and South were NOT equally matched either in their physical rail assets nor in their management of those assets. While the South had some moments of brilliance in their use of railroads, they simply did not have the infrastructure to maintain, let alone expand, the railroads of their region to their greatest advantage.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i] White, Charles, AMU CW500.

[ii, iv, v, vi, vii, viii, x, xi, xiii, xiv] Hansen, Peter A., Personal interview. Sept. 9, 2007

[iii, xii] Roland, Charles P. An American Iliad: The Story of the Civil War

[ix] McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom

[xv] Ziek, Thomas G., Jr., “The Effects of Southern Railroads on Interior Lines During the Civil War.” A Master’s Thesis.

Death and Injury on the Battlefield – Part I

On November 24th, I posted a piece on the impact of disease on soldiers in the Civil War [see “On Lice, Disease and Quinine” here]. The following discusses the other side of death during the war, the experience on the battlefield. Please be aware the the following is very graphic. [Photo to left: One of Ewell’s Corps as he lay on the field, after the battle of the 19th May, 1864. ]Battle injuries in the civil war were horrific and many led to death. The journals of soldiers and photographs of the dead tell of injury and death caused by cannon balls, grapeshot, canister, musket balls, bayonets, clubbing and more. Men were decapitated, cut in two, blown apart, shot in head, body, and/or extremities, bashed in the face or skull, disemboweled, burned, dragged, drowned, and/or suffered broken bones. John Beatty provided a glimpse of the carnage typical on most Civil War battlefields in a journal entry describing his pass through the battlefield of Stone River in Tennessee, early in 1863.

I ride over the battle-field. In one place a caisson and five horses are lying, the latter killed in harness, and all fallen together. Nationals and Confederates, young, middle-aged, and old, are scattered over the woods and fields for miles. Poor Wright, of my old company, lay at the barricade in the woods which we stormed on the night of the last day. Many others lay about him. Further on we find men with their legs shot off; one with brains scooped out with a cannon ball; another with half a face gone; another with entrails protruding; young Winnegard, of the Third, has one foot off and both legs pierced by grape at the thig

hs; another boy lies with his hands clasped above his head, indicating that his last words were a prayer. Many Confederate sharpshooters lay behind stumps, rails, and logs, shot in the head. A young boy, dressed in the Confederate uniform, lies with his face turned to the sky, and looks as if he might be sleeping. Poor boy! what thoughts of home, mother, death, and eternity, commingled in his brain as the life-blood ebbed away! Many wounded horses are limping over the field. One mule, I heard of, had a leg blown off on the first day’s battle; next morning it was on the spot where first wounded; at night it was still standing there, not having moved an inch all day, patiently suffering, it knew not why nor for what. How many poor men moaned through the cold nights in the thick woods, where the first day’s battle occurred, calling in vain to man for help, and finally making their last solemn petition to God![1]

Linderman posits that, even though the men fighting in the Civil War should have been more used to gore and death than those fighting in the next century, “when young soldiers first saw bullets, cannonballs, grapeshot, and canister strike others, their shock was profound. The first surprise was death’s suddenness,” a man alive and animated next to them one moment, and the next, lifeless and shattered. [2]Men splattered with the insides of the man next to them were even more impacted. Also shocking was the magnitude of death. It was not uncommon to see thousands of bodies after a single battle.[3]

Many men died agonizing deaths after lying injured on the field for hours or days. Contributing to this were standing orders that prevented a man from stopping his forward motion to help a fallen comrade. Some men were also fearful that doing so would imply cowardice on their part. Also, rarely could a truce be made to remove the injured and dead from the battlefield. The resulting experience for the injured was atrocious. Methods and procedures that would allow for application of first aid and then rapid transport to field hospitals were simply non-existent.

Disposal of bodies was often done carelessly and with little decorum if at all. Given the magnitude and ghastliness of the task, it is little wonder. Depending on the season, bodies awaiting burial, or even after careless burial, bloated and decayed in the heat and could be eaten by animals and insects. [Photo at right depicts the burial of soldier on one side and while an enemy soldier is left unburied.]Next installment… “Injuries on the Battlefield.”

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

Photos from the Library of Congress

[1] John Beatty, The Citizen-Soldier: The Memoirs of a Civil War Volunteer [book on-line] (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998, accessed 28 September 2007), 211; available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=26979264; Internet.

[2] Gerald Linderman, Embattled Courage: The Experiences of Combat in the American Civil War, 124.

[3] Ibid.

American Historian: George Bancroft

I’m back from Christmas break and trying to recuperate from a few too many cinnamon rolls. Reading assignments and preparation of a research proposal due Sunday are top of mind.

The class is Historiography so the research isn’t to be about the development and proof of a thesis. It’s more about research into the history of how history was written.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

Bancroft was one of the best known American historians of the 19thcentury. While Harvard educated (he entered at 13 and graduated at 17!), he is considered a “literary historian,” who wrote in a style popular with  the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

Perhaps less known is that Bancroft, while Secretary of the Navy, created the Naval Academy. He was also chosen by Congress to eulogize Abraham Lincoln. The New York Times reprinted that Eulogy on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the event in 1915. It, along with drawings of the event, can be seen in their entirety here.

I have located the index to his papers housed on microfiche at Cornell University and two biographies which leverage that material. The first, a two volume set 1971 reprint of M.A. DeWolfe Howe’s 1908 work The Life and Letters of George Bancroft, I was able to find on the Amazon Marketplace in almost pristine shape. The second, George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel, was written by Russel B. Nye and published in 1945. It’s on order. There are other large collections of Bancroft materials in holdings by the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. I’m beginning in earnest a search for articles that deal with his contributions to American history as well.

As a follow-up at some later point, I think it would be very interesting to contrast the style and impact  of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

You might recall that Charles and Mary Beard were the first to suggest that the Civil War was the second American revolution as was mentioned in my previous post here.

The exceptional oil on canvas portrait above of Bancroft in later life was painted by Gustav Richter, a German painter (1823 – 1884). It is a part of the Harvard University Portrait Collection and is on display at Memorial Hall.

More as I get into my research.

Photo credits:

Photo of George Bancroft in middle age taken by Mathew Brady, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo of painting above: The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as “Revolutionary”

[Note: This post is part of a series on The Civil War as Revolution which is available at the following links: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

————-

Indulge me while I – mull over and expound upon – one of Dr. McPherson’s essays in Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution.

If the mantel of “revolutionary” is worn by individuals who – because of their unique presence – drive transformational change, Abraham Lincoln must certainly be considered among them. Such a label might at first seem unfitting in that Lincoln was known for his conservatism. Indeed his early actions reflected caution and a desire for a limited, minimally disruptive war. His journey toward “revolutionary” took a big leap forward when the Border States ignored his repeated offers of graduated and compensated emancipation. His failure to sway them left him angry enough to, as McPherson phrased it, “embrace the revolution.” Lincoln’s “revolutionary” response? He issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the final version of which was delivered on New Year’s Day 1863. With it came a new “revolutionary” charter for the war: forceful overthrow of slavery and the South with it.

McPherson considers the enabling of black soldiers to fight and kill their former masters “by far the most revolutionary dimension” of Lincoln’s “emancipation policy.” And embrace it Mr. Lincoln did. Over 180,000 black soldiers would serve in Northern armies before the conflict ended. I must agree with Mr. McPherson’s conclusion that Lincoln evolved to fit the pattern of a revolutionary leader and became – once over his initial reluctance – arguably more radical than some of the founding fathers

District of Columbia. Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln

Civil War photographs, 1861-1865 (Library of Congress)

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

On Edward C. and CDVs

Harry Smeltzer over at Bull Runnings, in his kind mention of Wig-Wags yesterday, provides insight into the photo that tops my blog. He identifies it as being of “the Union signal station on Elk Ridge during the 1862 Maryland Campaign.” He points out that the officer in the photo (middle and seated) has been identified as one Edward C. Pierce. His CDV and story can be read “on the Save Historic Antietam Foundation (SHAF) website“ along with the full picture which I’ve also uploaded here for your viewing. Officer Pierce’s vitae is an interesting one and includes participation on Little Round Top at which time he held the rank of Captain. He remained, even though offered promotion in other areas, in the Signal Corps throughout the war.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, LC-B815- 633]

Elk Mountain, Md. Signal tower overlooking Antietam battlefield

O’Sullivan, Timothy H., 1840-1882 photographer.

I will set my ego aside for a moment and admit that I had to look up the term CDV. This may be familiar to most of you but since I’m a humble graduate student, I had to do a little research. It turns out that a CDV, or “carte-de-visite” (French for visiting card), is a small albumen print that – if of standard size – would be mounted on a backing card of 2.5 inches by 4 inches. This made them a handy size to use as a “photographic calling card” and they were exchanged and collected in albums. Debra Clifford, the “Town Historian of Ancestorville,” has provided an excellent history of the CDV on the Ancestorville.com site and indicates that “a young Civil War soldier would proudly send his “likeness” home to a waiting beau, mother and family.”

Albumen (al-bu-men) means, by the way, “the white of eggs.” I assume that egg whites were used to provide a glossy finish to the photo. The technique was developed and patented by Andre Disderi in 1854 and, according to Clifford, introduced in the United States in 1859 which positioned it perfectly for adoption by young men going off to war. “…CDV’s were produced in the millions. The ease of size and paper format of this newfangled photograph allowed the CDV to be sent through the mail, a great benefit from the heavily glassed and protected and cased ambrotype and daguerreotype photos that were previously available.”

This CDV is of Daniel Edgar Sickles is a part of a collection wonderfully preserved and presented for our virtual viewing on the American Memory section of the Library of Congress site along with some two hundred others. These make up the collection of John Hay who was a personal secretary to President Abraham Lincoln and so had occassion to receive CDVs from an assortment of people of the era including “army and navy officers, politicians, and cultural figures.”

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, LC-MSS-44297-33-116 (b&w negative)]

Photographer: Sarony, Napoleon (1821-1896)

Collection: James Wadsworth Family Papers

The Siege of Charleston – The Stone Fleet

“The Siege of Charleston” is a fascinating chapter in The Lost Cause: Myths and Realities of the Confederacy (see previous post) by William C. Davis, and provides excellent information about naval operations in the area over the course of the war. I found of particular interest that Lincoln packed a couple of fleets of aged merchant and whaling ships with granite and floated them into the mouth of the harbor where he had them intentionally scuttled. The obvious intent was to foil those who would run the blockade. I found conflicting references as to the utility of the tactic. Davis indicated that the bottom was soft and so they sunk into the muck and accomplished little. But other sources indicate that the main channel off of Morris Island was blocked for at least some period of time. But that didn’t sufficiently slow blockade runners and so a second Stone Fleet was launched in early 1862 and its twenty ships sunk.

The good folks over at sonofthesouth.net have provided a copy of the December 14, 1861 issue of Harper’s Weekly which features a story about and a sketch of the fleet “as seen by the brig Castillian on Nov. 21.” Dubbed by Harper’s as “The Rat-Hole Squadron,” the story chronicles the sorted history of one of the whaler’s headed for the bottom.

Herman Melville’s poem titled “The Stone Fleet” published in December, 1861, names several of the ill-fated ships. You can read it in its entirety on Print Read. He wrote prolifically about the Civil War and this and other war-related works can be found in Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War.

Herman Melville

Harry Smeltzer over at Bull Runnings has pictures of the Charleston Harbor in a post on his blog that’s definitely worth a look-see.

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

Straight talk on soldiers and presidents

I’m reading The Cause Lost: Myths and Realities of the Confederacy by William C. Davis. The approach Davis has taken is to profile the primary players in the conflict – foibles and all. W. C. presents a fascinating portrait of Jefferson Davis which borders on being psychoanalytic. It helps to explain why Davis and his generals had such poor relationships, the exception being Lee who was a master at determining how to handle the man and won his loyalty and friendship. Three of Lee’s practices stood out. First, he kept Davis informed on a daily basis – unlike Beauregard and Johnston. Second, he asked Davis for his opinion, which stroked his ego. Third, he stayed away from the press and didn’t criticize Davis behind his back. Lee’s peers struggled with either their own self-importance or lack of ability and found outlet by back-biting in the press.

All in all a very good read largely because Mr. Davis pulls no punches. Also worth the read because of the details provided; case in point, the sinking of the “Stone Fleet” at the mouth of the harbor leading into Charleston. This strategy by the Federals to block traffic in and out of the harbor failed miserably due to the soft mud bottom into which the fleet – whose holds were filled with granite – sank.

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

!["The Fight Between the Alabama and the Kearsarge" [NH59354]](https://wigwags.files.wordpress.com/2008/09/the-fight-between-the-alabama-and-the-kearsarge-nh59354.jpg?w=444&h=351)

![[Charleston Harbor, S.C. Deck and officers of U.S.S. monitor Catskill; Lt. Comdr. Edward Barrett seated on the turret].](https://i0.wp.com/memory.loc.gov/service/pnp/cwpb/02900/02975r.jpg)