Posts Tagged ‘Border Wars’

A Civil War Border Killing

A friend recently found a newpaper article regarding the death of his wife’s great grandfather, published below with permission. Since I live near the border of Missouri and Kansas and have posted quite a bit on our Civil War era border wars, I found this particularly interesting.

Note that Elwood, Kansas (originally called Roseport) is directly across the Missouri River from St. Joseph, Missouri.

St. Joseph Morning HeraldThursday September 11, 1862

Killing in Elwood (Kansas). Last Thursday a Mr. Slaughter was killed in Elwood by some Federal soldiers from Troy. We heard different versions of

the affair, at the time, and declined to publish any of them. Yesterday Mr. John Norton of Elwood, who lives with the Coroner, and was the

first man on the ground after the killing, brought us the following account of the affair, obtained from Mrs. Slaughter, the wife of the deceased:

Samuel A. Slaughter, living in Elwood, was killed Thursday night Sept 4, about 1 o’clock, as follows: A man named Day was living in

the house with the deceased. The soldiers came to the door which was left open, and began ballooing for the man of the house. Mr. Day asked

them what they wanted, and they replied, “A light.” He immediately struck a light, and they then asked him if a man named Slaughter lived there.

He replied affirmatively. They told him to tell Slaughter they wanted to see him. Mr. S. put on his clothes, went to the door, and asked them

what they wanted of him. They replied, “No matter, come along with us.” They took him out of the yard, and as soon as he was outside the gate, a revolver was fired. After the firing, the soldiers twice cried “halt.” They then cried, “There is a dead man out here, come and take care of him.”

Mr. Day and Mrs. Slaughter went out there, found Mr. Slaughter dead, ‘roused some of the neighbors, and procured a Coroner. The soldiers forbid them holding an inquest. They said they were there to arrest Mr. S. and he ran from them, and none should be held.

Mr. Slaughter was a secessionist, aged 26 or 28 years, and leaves a wife and two children. He formerly lived in this city, and once kept a

small saloon by the Elwood Ferry landing, called “The First and Last House.”

Elwood, first called Roseport, was established in 1856. In its heyday scores of river steamboats unloaded passengers and freight at its wharves and every 15 minutes ferryboats crossed to its Missouri rival, St. Joseph. During the 1850’s thousands of emigrants outfitted here for Oregon and California. Late in 1859, Abraham Lincoln seeking the Republican nomination, here first set foot in Kansas, and spoke in the three-story Great Western Hotel. Elwood was the first Kansas station on the Pony Express between Missouri and California. Construction of the first railroad west of the Missouri river began here in 1859. On April 23, 1860, the first locomotive, “The Albany,” was ferried over and pulled up on the bank by hand. Elwood’s ambitions for greatness were thwarted, not by St. Joe, but by the river which undermined the banks and washed much of the old town away.

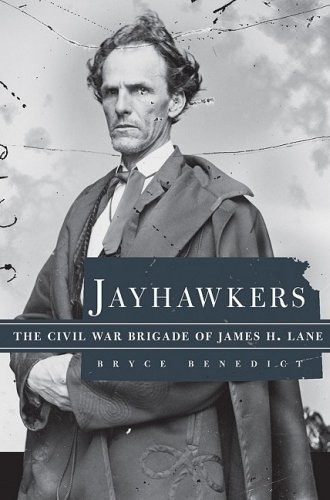

Jayhawkers: The Civil War Brigade of James Henry Lane

ISBN: 978-0-8061-3999-9

Cloth

352 pages

12 b&w illus., 1 map

Published: 2009-04-30

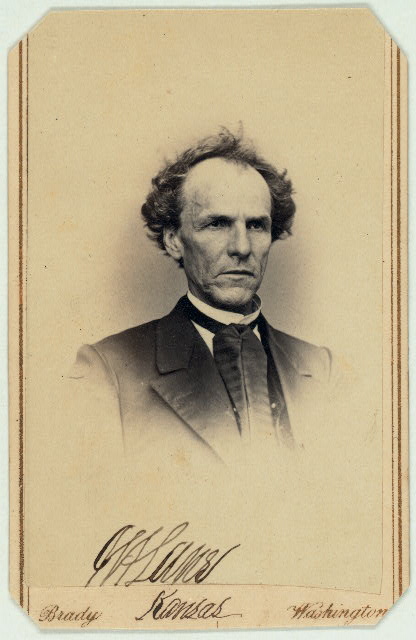

Carte d' visite of James Henry Lane, 1814-1866 Photographer: Brady National Photographic Art Gallery (Washington, D.C.) Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-MSS-44297-33-037 (b&w negative)

The good folks at the University of Oklahoma Press sent me a review copy yesterday of Bryce Benedict’s Jayhawkers: The Civil War Brigade of James Henry Lane. In my usual fashion, I’m posting a few comments prior to a thorough reading.

I live on the borders of Missouri and Kansas so confess some considerable fascination with both Jim Lane and the evolution of war in the towns and farmlands of this part of the Western theater. Lane, a Kansas senator and strong advocate of Lincoln, was a player. Benedict identifies Lincoln himself as having given Lane authority “to raise and command two volunteer regiments.” Lane used them to harass Missourians with violence, theft, and destruction of property in a manner foreshadowing that of Sherman. Benedict posits that Lane thus embraced the notion of “total war” as a means of disabling the enemy’s war machine before it became more widely adopted as a strategy of the Union.

The photo of Lane on the cover (above) was a brilliant choice. After perusing the Library of Congress and finding his carte d’visite (left), it becomes clear that the look of the man fit his personality. In the words of Milton W. Reynolds, Lane was “weird, mysterious, partially insane, partially inspired, and poetic.” He described him as having lived a “…wayward, fitful life of passion and strife, of storm and sunshine a mysterious existence that now dwelt on the mountain-tops of expectation and the very summit of highest realization, and anon in the valley of despondency and deepest gloom.” [1] Lane committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth with a pistol in 1866.

Author Bryce Benedict has produced a well researched work with notes for each chapter and three appendices including considerable information about fate of the casualties of Lane’s brigade, most of whom died from disease.

—–

For further reading, check out these books digitized for online reading at the Library of Congress.

[1] Connelley, William Elsey, (1855-1930) James Henry Lane, the “Grim chieftain” of Kansas (Topeka: Crane, 1899). The Library of Congress Digitized Book. LOC Call number: 9594581, Digitizing sponsor: Sloan Foundation

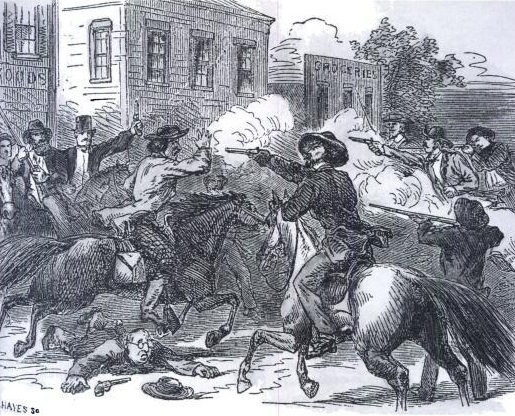

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 7 The Deed

Sacking of Lawrence, 1856

This post completes the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, and Part 5 here, Part 6 here.

Free-State men wounded Douglas County sheriff Samuel J. Jones when he returned to Lawrence to serve arrest warrants in the spring of 1856, despite the presence of Federal troops. The Grand Jury of Douglas County met and “returned indictments against three free-state leaders, against two newspapers at Lawrence – the Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State – and against the Free State Hotel at Lawrence, which, it said, was in fact a fortress, “regularly parapeted and portholed for use of small cannon and arms.” (Potter, 208) There is good evidence that the hotel was, in fact, designed with a mind toward defense with filled portholes that could be knocked out with a rifle butt. But it is curious that indictments of treason were levied toward an inanimate building.

To serve the indictments and associated arrests, United States Marshal Israel B. Donaldson raised a posse inclusive of Missourians. But he left them outside of town as he arrested, along with a deputy, several minor players, others having fled. (Potter, 208) He then attempted to disband the posse but Sheriff Samuel J.Jones, healed of his wounds, rallied the men and rode into Lawrence as a mob force “alleging the need of aid in making arrests and abating nuisances under authority of the grand jury.” (Malin)

To serve the indictments and associated arrests, United States Marshal Israel B. Donaldson raised a posse inclusive of Missourians. But he left them outside of town as he arrested, along with a deputy, several minor players, others having fled. (Potter, 208) He then attempted to disband the posse but Sheriff Samuel J.Jones, healed of his wounds, rallied the men and rode into Lawrence as a mob force “alleging the need of aid in making arrests and abating nuisances under authority of the grand jury.” (Malin)

Samuel J. Jones

Michael Holt describes the events of May 21, 1856 as the work of a posse sent by the Lecompton government “to arrest several free state leaders in Lawrence.” (Holt, 194) That posse, “which included Missourians, burned some buildings and destroyed two printing presses but killed no one in the town.” (Holt, 194.) Put in that way, it sounds relatively benign but was pounced on by the Republicans as evidence that the Pierce-backed Kansas territorial government was supporting and condoning atrocities.

“The War Actually Begun,” “Triumph of the Border Ruffians,” “Lawrence in Ruins – Several Persons Slaughtered,” “Freedom Bloodily Subdued,” hyperbolized the Eastern Republican press.” (Holt, 194.) “Kansas was bleeding because lawless slaveholders were butchering defenseless northern settlers in their effort to force slavery on the territory.” (Holt, 194.)

The raid targeted the Free-State Hotel, a building constructed and owned by the New England Emigrant Aid Company. Griffin confirms that Douglas County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones led the posse. He and his men “bombarded the [Free-State] hotel with cannon and then gutted the building with gunpowder and flame. The razing of the hotel, together with the burning of Charles Robinson’s house, the wrecking of the equipment of two newspapers, the Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State, and a certain amount of looting and vandalism, became known as the ‘sack of Lawrence.’” (Griffin)

"Old Sacramento Cannon" captured by U.S. during the Mexican-American War in 1847 and taken to the Liberty Arsenal. The cannon was seized by pro-slavery forces in 1856 and fired during the Sacking of Lawrence. The cannon was damaged in 1896 when it was loaded with clay and straw and fired. Source: Wikipedia Commons

Griffin further claims that proslavery men in the territory justified the action by claiming Jones and his men “were simply executing an indictment of the grand jury of the United States district court at Lecompton and the orders of the presiding judge, Samuel D. Lecompte.” (Griffin)

Samuel D. Lecompte

“Free-State men were quick to agree with their enemies, but contended that judge, jury, and Jones had acted illegally and without cause. Newspaper editors sympathetic to the Free-State cause gave the affair enormous publicity — much of it merely falsehoods — and labored to convince their readers that the sack of Lawrence was yet another manifestation of Proslavery barbarism. Before a month was out, Kansas mythology was immensely richer.” (Griffin)

As a final note, both Malin, Griffin, and Holt contend that no one was killed in the raid on Lawrence. But Potter points out that one man, a slave, was killed from falling debris as the Free State Hotel was demolished. (Potter, 209) Clearly it was violent event amidst growing episodes of violence between Free-State and proslavery factions along the border between Kansas and Missouri.

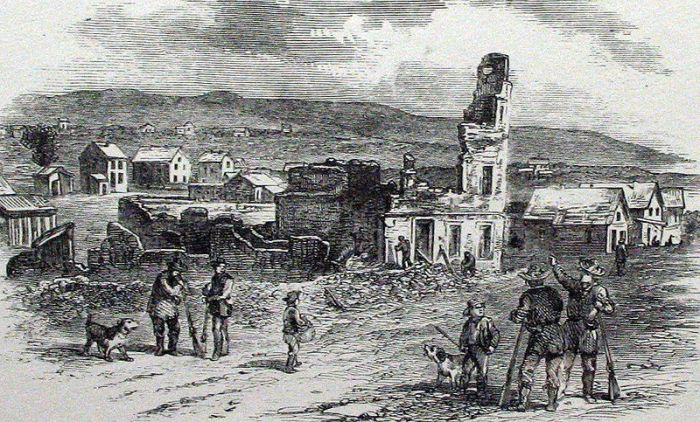

Ruins of the Free State Hotel, after the Sacking of Lawrence, Kansas, 1856

——

C. S. Griffin, “Kansas Historical QuarterlyThe University of Kansas and the Sack of Lawrence: A Problem of Intellectual Honesty,” Kansas Historical Quarterly, Winter, 1968 (Vol. XXXIV. No. 4), pages 409 to 426. Accessed online, February 14, 2009.

Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s, (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1983).

James C. Malin, “Judge Lecompte and the ‘Sack of Lawrence,’ May 21, 1856, ” Kansas Historical Quarterly, August 1953 (Vol. 20, No. 7), pages 465 to 494. Accessed online, February 14, 2009.

David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976).

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 6 The Wakarusa War

Samuel J. Jones

David Potter suggests that much of the discord between Kansans and Missourians was less about slavery and more about land claims.(i) The territory had not yet completed land surveys even six months after it opened for settlement so people squatted on land they wanted. Disputes over those claims, largely between Missourian and new Kansan settlers, sparked the events that culminated in the 1856 raid on Lawrence.

Samuel N. Woods

It began with a killing. A pro-slavery man named Franklin N. Coleman killed in 1855 a Free-Soiler named Charles W. Dow south of Lawrence, Kansas in a land-claim dispute. [An account of the killing by Isaac T. Goodnow can be read here.] Because Coleman claimed self-defense, he was not arrested. In retaliation, a group of Free-Soil men threatened Coleman and his corroborators and burned their property. (ii) Douglas County sheriff Samuel J. Jones was sent to arrest the aggressors but was prevented from doing so by armed Free-Soil men lead by Samuel N. Wood.

Wilson Shannon

Jones accepted the aid of an army of Missouri “Border Ruffians” who converged outside of Lawrence near the Wakarusa River with the intent of enforcing “Law and order in Kansas.” (iii) Then Kansas Territory governor Wilson Shannon averted violence through negotiation (President Pierce refused him Federal troops) and the band dispersed, albeit reluctantly. Because the threat of violence was so great, the episode became known as the Wakarusa War.

Wakarusa River near Lawrence, Kansas - Source: KansasExploring > Larry Hornbaker > Events > Blanton's Crossing

This post continues the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, and Part 5 here.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(ii) Ibid., 207.

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 5 Beecher’s Bibles

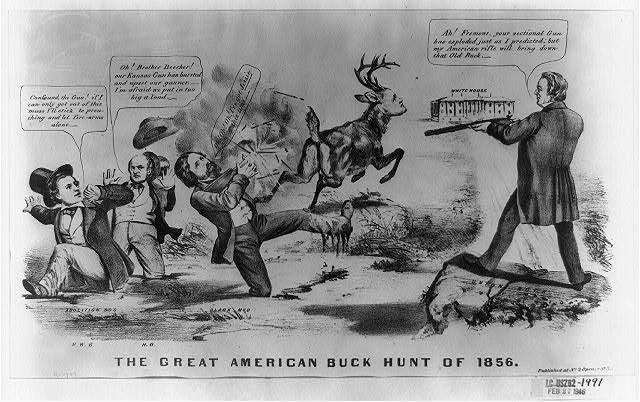

Digital ID: cph 3b37012 Source: b&w film copy neg. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-90663 (b&w film copy neg.) , LC-USZ62-1991 (b&w film copy neg.) Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

The potential for violence after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and indeed episodes of violence, increased on the border between Missouri and Kansas as both Free Soiler and pro-slavery factions began actively arming themselves. An agent of the New England Emigrant Aid Society in Kansas, Charles L. Robinson, requested with some urgency a shipment of several hundred rifles and field guns.(i) Guns were sent to aid Free Soilers in Kansas often with the support of northeastern clergy and their congregations. Thus Sharps Rifles sent by Henry Ward Beecher’s congregation became know as “Beecher Bibles”. Likewise, according to Potter, armed militias from the South began forming to support the pro-slavery cause in Kansas. (i)

Henry Ward Beecher (Source: Library of Congress Brady-Handy Photograph Collection (LC-BH82- 5388 A))

This post continues the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, and Part 4 here.

ABOUT THE POLITICAL CARTOON: Another Currier satire favoring American party candidate Millard Fillmore. A “buck” (James Buchanan) runs toward the White House, visible in the distance, as the two rival candidates take aim at him with their shotguns. Republican John C. Fremont’s gun explodes (left), as he struggles to free himself from a pool of “Black Mud.” On the far left his two abolitionist supporters Henry Ward Beecher and editor Horace Greeley are also mired in an “Abolition Bog.” Fremont: “Oh! Oh! Oh! I’ve got Jessie this time–” (a puzzling allusion to his wife Jessie Benton). Greeley: “Oh! Brother Beecher! our Kansas Gun has bursted and upset our gunner. I’m afraid we put in too big a load.” Reference is to the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 and the ensuing violence in Kansas, an issue exploited by the Republicans. Beecher: “Confound the Gun! if I can only get out of this muss I’ll stick to preaching and let fire-arms alone.” The oblique reference to Beecher’s part in outfitting armed antislavery emigrants for Kansas is made in more obvious terms in “Col. Fremont’s Last Grand Exploring Expedition in 1856” (no. 1856-20). On “Union Rock” (right), which is square in the path toward the White House, stands Millard Fillmore. He aims his flintlock at Buchanan and says confidently, “Ah! Fremont, your sectional Gun has exploded just as I predicted; but my American rifle will bring down that Old Buck.” MEDIUM: print on wove paper : lithograph ; image 24 x 39 cm. CREATED/PUBLISHED: N.Y. : Published at No. 2 Spruce Street, [1856] Source: Library of Congress

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 4

An illustration shows men lining up to vote on the issue of slavery in Kansas Territory. In 1855 voters chose to allow slavery. The Granger Collection, New York

The actual number of free-state settlers that made it to Kansas was far more modest than the expectations set in the press but the perception was in the public psyche.

Andrew Reeder

When the Kansas Territory’s first governor, Andrew Reeder, called for elections of the Kansas Territorial Legislature on March 30, 1855, pro-slavery Missourians crossed the border in droves and took advantage of a poorly conceived suffrage law that required little to no proof of residency to vote. The government they elected was widely recognized as bogus but Reeder let the election stand and President Franklin Pierce endorsed it. The new government created exceptionally pro-slavery laws, some verging on the absurd. Free-state men revolted by setting up their own shadow government in Topeka claiming that its laws and elected officials would become legitimate once statehood was achieved. This exacerbated further the rift between the two factions and opened the door for the Lecompton government to take legal action against the free-soil men, indeed eventually accusing some of treason.

“If one government was valid, the other was spurious, either morally or legally, as the case might be. If the acts of one were binding upon the citizens, then submission to the authority of the other by, for instance, paying its taxes or serving in its militia would constitute sedition, or even treason.” (i)

Polarization of the factions increased.

——

This post continues the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.