Archive for the ‘Military Philosophy’ Category

The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare

Edward Hagerman. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. Reprint. Indiana University Press, 1992.

In this important work on tactical and strategic military history, Edward Hagerman posits that the American Civil War marshaled in a new era in land warfare colored by the impacts of the Industrial Revolution. He argues that the complete command and control systems of armies was impacted by factors both occurring across the globe (i.e. technological developments in weaponry and transportation) and unique to America: its culture, geography, and history.

In this important work on tactical and strategic military history, Edward Hagerman posits that the American Civil War marshaled in a new era in land warfare colored by the impacts of the Industrial Revolution. He argues that the complete command and control systems of armies was impacted by factors both occurring across the globe (i.e. technological developments in weaponry and transportation) and unique to America: its culture, geography, and history.

Hagerman is clear in setting two broad aims for the book. The first is to provide a new analysis of the “theory, doctrine, and practice of field fortification in the tactical evolution of trench warfare.” The second is to analyze the development of field transportation and supply and its impact of the movement and maneuvering of Civil War armies

Hagerman organizes his study around several themes. The first addresses the ideas and education that informed the American military including the influence of theorists such as Jomini, Clausewitz, and at West Point, Dennis Hart Mahan. Secondly he looks at the organizational change, or lack thereof, in the Army of the Potomac including an explanation of the educational orientation of its leaders. Thirdly he explores the Army of Northern Virginia and the culture and traditions which informed men of the south who entered the military. Next he dives into the emergence of trench warfare and the strategic and tactical evolution that resulted from it. And importantly, he finishes with the evolution of total war and the strategy of exhaustion.

This work should be of particular interest to military historians and even more so to those interested in the American Civil War and its impact on military logistics, the use of technology, weaponology, military tactical and strategic thought, and the concepts of modern warfare and its history.

There is an extensive notes section valuable to the serious student of military history. This is augmented by a “Works Cited” section including listings of primary sources. The introduction to the book provides an exceptional summary of many of the key factors that impacted the war.

Edward Hagerman brings to this study the credentials of academician. He was Associate Professor of History at York University in Toronto, Canada at the time of the book’s publication. He is also the recipient of the Moncado Prize of the Society of Military History.

Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea

Belatedly, I want to mention that I’ve received a pre-publication copy of Noah Andre Trudeau’s Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea, which I’ll hope to provide a full review of before too long. At first blush, it appears to be an excellent read.

Since this book falls into the category of Civil War Campaigns, I’ve added a shelf in my virtual bookstore to accommodate it which you can find here.

As a student of military history, one of the many things that I find so fascinating about Sherman’s march is that its destructive power encourages its consideration as “total war” a la Clausewitz. Can’t wait to dig in to this one.

For those of you in the Chicago area, Mr. Trudeau’s publisher Harper Collins, indicates that he will be publicizing his book at the following on Thursdays.

05:00 PM – 07:30 PM

PRITZKER MILITARY LIBRARY

2nd FL 610 N Fairbanks Court Chicago, IL 60611

Scientific Optimism: Jomini and the U.S. Army

Those of you who follow my postings know that I’ve ruminated a bit on Jomini (pictured above). You can find the complete list of related posts here. For those who find discussion of Jomini and Clausewitz interesting, I wanted to pass along a link to an excellent essay by Major Gregory Ebner titled “Scientific Optimism: Jomini and the U.S. Army” available here. Ebner, in an essay that appears as a featured article in The U.S. Army Professional Writing Collection, makes a case for how the U. S. Army presents itself as a Clausewitzian organization at upper levels but is “firmly rooted in the ideals of Antoine-Henry Jomini” at the tactical and operational levels. He posits that focus on “good staff work and the military decision-making process (MDMP)” reflects a reliance on military science and method over the application of genius as espoused by Clausewitz. He further suggests that the Principles of War developed by the U.S. Amy was an encoding of Jomini in the form of doctrine. This essay is instructive to the study of military philosophers and military thought on several fronts. First, for the military philosophy student, it reinforces the theories of both Clausewitz and Jomini and would therefore make an excellent reading assignment after studying the primary works of both theorists. Second, it provides insight into the extent to which the largest army in present day has adopted and incorporated the ideas of both men at the doctrinal and operational levels.

For more information:

MDMP – Military Decision Making Process

Access “The Clausewitz Homepage” here.

Military History Book of Interest: Napoleon on the Art of War

Bonaparte, Napoleon. Napoleon on the Art of War. trans. and ed by Jay Luvaas. New York: Touchstone, 1999.

Jay Luvaas has pulled together in a single work what Napoleon never set to paper – a cohesive, single treatise on his philosophy of war. Luvaas, a respected military historian, accomplished this by reviewing, organizing, translating and editing Napoleon’s writings over the course of his life including much of his correspondence. He has organized the book into a series of essays so that it is structured not unlike the work of other military theorists. It begins with Napoleon’s views on creating a fighting force and preparations for war. This is followed by his thoughts on military education – an area about which Napoleon was passionate – particularly as related to the study of “great captains” of history: Alexander the Great, Hannibal, Caesar, Gustavus Adolphus, Turenne and Frederick the Great.. A section on “combat in arms” reveals Napoleon’s brilliance in changing up formations utilizing the men, animals and weaponry at hand. “Generalship and the art of command,” army organization, strategy, fortification, the army in the field, and the operational art are also examined through Napoleon’s writings with additional historical references as well as reference to correspondence written about major Napoleonic campaigns. This book is instructive to the study of military philosophers and military thought in that it provides insight into one of the most influential militarists in history. Military thought leaders such as Clausewitz and Jomini were contemporaries of Napoleon and highly influenced themselves by strategizing to fight with or against him. The book fills a rather noticeable gap and would be an excellent addition to any examination of military philosophers and strategists.

On the Temperment of Military Leaders – I

The review of Jomini’s theories on the art of war brought back some thoughts about the purpose of military philosophy itself and a debate we had in class over whether the conduct of war – in all of its complexity – should be reduced to principles, systems, models, tactics, etc. I suggested that war has both quantifiable and unquantifiable aspects. Arguably, it is the unquantifiable – human passions, values, and beliefs – that bring us to war as nations and as individuals. These same things certainly contribute to war’s unpredictability. To mitigate against the unpredictable, we focus on that which is quantifiable: structure, planning, training and execution. Systems, categorization and modeling allow better problem solving, preparation, and control. In war, as in any complex human endeavor, they can also reduce the risk of failure and conversely increase the probability of “the win.”

The review of Jomini’s theories on the art of war brought back some thoughts about the purpose of military philosophy itself and a debate we had in class over whether the conduct of war – in all of its complexity – should be reduced to principles, systems, models, tactics, etc. I suggested that war has both quantifiable and unquantifiable aspects. Arguably, it is the unquantifiable – human passions, values, and beliefs – that bring us to war as nations and as individuals. These same things certainly contribute to war’s unpredictability. To mitigate against the unpredictable, we focus on that which is quantifiable: structure, planning, training and execution. Systems, categorization and modeling allow better problem solving, preparation, and control. In war, as in any complex human endeavor, they can also reduce the risk of failure and conversely increase the probability of “the win.”

All of that said, I would suggest that there are deeper reasons why those responsible for the conduct of war focus on systems and organization and it has to do with their innate personalities. While there is debate about whether successfully military leadership can be attributed to personality type, I believe that there is good evidence that it can. David Keirsey and Marilyn Bates built upon the research of Carl Jung (archetypes), Katheryn Briggs, Isabel Myers (Myers-Briggs Trait Indicator), and a host of others in identifying distinct types of personalities. Keirsey introduced the concept of “temperaments” which, he suggests, “places a signature or thumbprint on each of one’s actions, making it recognizably one’s own.” While I won’t go into details on the building blocks of the temperaments, I will focus on description of those traits Keirsey suggests are often seen in commanders of the military and I’ll give an example from the Civil War. It’s fascinating stuff. More in the next post…

Jomini on the Nature of War – Part IV – The Basics

This post continues from Jomini on the Nature of War: Part I Introduction here, Part II The Burgeoning Military Theorist here, and Part III The Founder of Modern Strategy here. Please note links in blue lead to additional information on those topics.

.

Jomini was a list maker and a categorizer which influenced the form of his thoughts on the nature of war. His work, The Art of War, begins with a definition of the art of war in terms of five military branches: Strategy, Grand Tactics, Logistics, Engineering and Minor Tactics.

Jomini was a list maker and a categorizer which influenced the form of his thoughts on the nature of war. His work, The Art of War, begins with a definition of the art of war in terms of five military branches: Strategy, Grand Tactics, Logistics, Engineering and Minor Tactics.

Strategy – “the art of properly directing masses upon the theater of war either for defense or for invasion; the art of making war upon the map.”

Grand Tactics – “the art of posting troops upon the battle-field according to the accidents of the ground, of bringing them into actions, and the art of fighting upon the ground, in contradistinction to planning upon a map.” It is “the maneuvering of an army upon the battle-field, and the different formations of troops for attack.”

Logistics – “the art of moving armies and the execution of strategical and tactical enterprises” and “comprises the means and arrangements which work out the plans of strategy and tactics.”

Engineering – “the attack and defense of fortifications.

Minor Tactics

Jomini adds a sixth branch which he calls, “Diplomacy in its relation to War.” This he envisions as the role of the statesman in war and particularly in those activities which lead up to it. He provides the criteria from which a statesman can conclude whether a war is “proper, opportune, or indispensable.” He lists succinctly and thoroughly his perspective on the reasons why a government would choose to enter into war:

- “To reclaim certain rights or to defend them;

- to protect and maintain the great interests of the state, as commerce, manufactures, or agriculture;

- to uphold neighboring states whose existence is necessary either for the safety of the government or the balance of power;

- to fulfill the obligations of offensive and defensive alliances;

- to propagate political or religious theories, to crush them out, or to defend them;

- to increase the influence and power of the state by acquisitions of territory;

- to defend the threatened independence of the state;

- to avenge insulted honor; or

- from a mania for conquest.”

Each reason becomes a “type” of war on which Jomini elaborates with examples from history. The type of war,  he suggests, “influences in some degree the nature and extent of the efforts and operations necessary for the proposed end.”

he suggests, “influences in some degree the nature and extent of the efforts and operations necessary for the proposed end.”

Should you have interest in reading de Jomini’s The Art of War, it is available both on Google Books here and at Project Gutenberg here.

——

Jomini, Antoine Henri de. The Art of War, trans. by G. H. Mendell and W. P. Craighill., Special Edition, (El Paso: EL Paso Norte Press. 2005), 9.

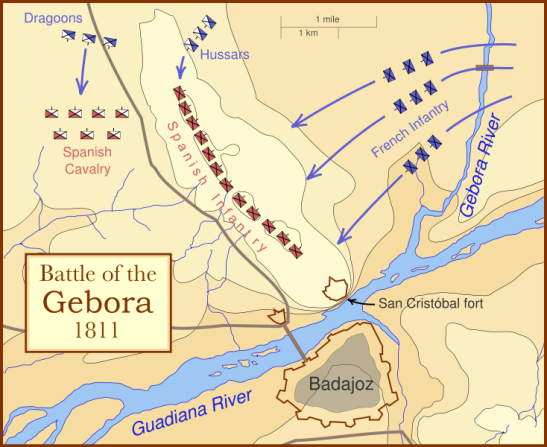

A map for the w:en:Battle of the Gebora, in 19 February 1811. Source can be found here. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document (refers to map) under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation license“.