Posts Tagged ‘Historiography’

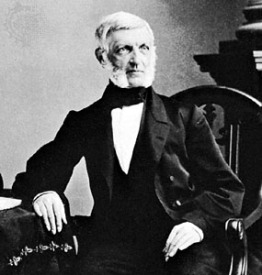

Academic Book Review – George Bancroft

George Bancroft. By Russel B. Nye. New York: Washington Square Press, Inc. 1964. Bibliography. Pp. x, 212. $.60.

If biographies written in the twenty-first century tend toward tomes, Russel Nye’s 1964 work on George Bancroft, the most acclaimed American historian of the nineteenth century, demonstrates how to impress with a modicum of words. Though Bancroft’s life spanned almost a century, Nye skillfully paints a portrait of the man against the sweeping landscape of the United States’ passage from fledgling country at the turn of 18th century to battle-scarred nation ninety years later, all in fewer than two hundred pages.

Nye’s book is part of the Washington Square Press “Great American Thinkers Series,” targeting an audience of general readers as well as serious secondary and college students who want readable history. George Bancroft as subject is in good company among other well known Americans included in the series, like Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John C. Calhoun. Series editors provided a general outline for Nye to follow, which included a short biography of the subject, a critical evaluation of his central ideas, and his influence upon American thought as a whole.

Nye approaches the task in a somewhat unconventional manner. He begins and ends with reasonably standard material. A chronology of key events in Bancroft’s life is placed in the front matter of the book, beginning with his birth in 1800 and ending with his death in 1891. End materials include a list of Bancroft’s extensive published works and a complete bibliography and index. It is in the book’s narrative that Nye shows structural creativity. He reveals Bancroft by coming at the subject from six different directions: life history, views on education, artistic and cultural perspectives, formation as a politician, views on humanity and the divine, and Bancroft’s contribution to historiography.

The first chapter, titled “The Pattern of a Life,” provides a highly readable narrative overview of Bancroft’s ninety-one years. Nye begins with the family and culture into which Bancroft was born, and then explores his passage through school years, including entry into Harvard at the age of 13. His formative years studying abroad are covered next, and insight is provided into the effects that European intellectuals and artists had on the now young man. Nye brings Bancroft home to the United States, doctorate in hand, and traces his quest for direction in life that leads him away from ministry and into politics and writing. His life as politician and as an emerging and then accomplished historian are described, as well as the events that bring a close to Bancroft’s life.

Nye devotes the entire second chapter, “Experiment at Round Hill,” to Bancroft’s daring project as schoolmaster of a preparatory school for boys in New England. Partnering with a colleague from Harvard, Bancroft incorporates in the endeavor the progressive concepts in education he observed while in Europe. But Bancroft has a love-hate relationship with teaching, and gradually realizes that his destiny lies elsewhere. As the chapter closes, he has sold his interest in the school to his partner and moved on, having left his mark on the history of American education as the creator of the first high school and a modeler of educational reform.

In the third chapter, “The Anatomy of Culture,” Nye explores the Romantic Movement’s impact on Bancroft and his contemporaries, and makes good use of the subject’s actual writing. Excerpts of Bancroft’s early attempts at poetry are presented by way of showing that, while his own poetic work was amateurish, he was able to channel his love for art into the role of literary critic, becoming quite adept at it. Nye does a masterful job of showing, through excerpts of Bancroft’s reviews and critiques, not only his appreciation of the artistic, but his gift for seeing broad themes like democracy in art. He also shows how Bancroft was able to bring his interest in artistic judgment and creation to his growing preoccupation with history. Instead of losing touch, “he absorbed his interest in art into the larger context of his theory of culture and his concept of history. To him, as to his contemporaries, the boundaries of intellectual specialization were fluid” (63). This fusion of the literary with history defined Bancroft’s historical writing. Nye’s ability to correlate the cultural milieu of early 19th century with Bancroft’s growth as philosopher, theologian, artistic critic, and historian is particularly well done.

Chapter 4, “The Fabric of American Political Life,” guides the reader through Bancroft’s life as a politician, and his metamorphosis into a Jacksonian democrat and political thinker. Again, Nye identifies themes from Bancroft’s writings and personal correspondence, including the idea that political figures are heroes to the populations they serve. Nye closes the chapter with a moving description of Bancroft’s role as eulogizer of Lincoln, a man who Bancroft grew to consider as a hero of some stature through the course of the Civil War. He also traces Bancroft’s evolving views on slavery.

In Chapter 5, “Nature: Human and Divine,” Nye explores how Bancroft came to his religious beliefs and his philosophical stand on the nature of humanity and the divine. This is an important topic because Bancroft’s theological thinking informed much of his historical writing and speaking. Nye shows Bancroft as a man of his times, influenced by the enthusiasm of a country running toward a bright future, and yet a man who contributed much to that nation because of his study abroad and exposure to many of the world’s foremost thinkers. Nye does a good job of showing how Bancroft reconciled his belief in man’s free will as long as it was exercised within the larger will of the divine.

In his final chapter, “The Shape and Meaning of History,” Nye looks as Bancroft the historian and the influence of his historiography. He provides an excellent overview of the state of historical study at the turn of and into the early 19thcentury, contrasting rationalistic historical theory against Romantic history a la Rankian Zeitgeist. His review of the expectations of historical writers in Bancroft’s generation is excellent. But most important in this chapter are the selections from Bancroft’s own essays, illustrating how he conceived of his own calling. His personal philosophy, which he put to paper not long after returning from studies in Europe, placed the office of the historian second only to the poet in its noble call to find God within history.

This perspective, Nye informs, pervaded the first three volumes of Bancroft’s most famous work, The History of the United States of America from the Discovery of the Continent, in which it was clear “that he was convinced that the United States was the creation of Divine Providence” (158). The second theme was that of man’s right to pursue freedom. Nye takes the reader through the completion and then revision of the seven volumes which took place over the course of most of Bancroft’s remaining life. He touches upon the influences of the American Civil War on his writing, and particularly on the volumes having to do with the Revolutionary War. Nye gives insight into Bancroft’s work style and ethic, as reflected in a two-volume work on the American Constitution. He interjects some deserved criticism of Bancroft who, he suggests over simplified the events surrounding the Constitution’s creation, ignoring “the whole tangled skein of economic and political rivalries, conflicting interests, and clashing personalities” (170).

Nye leaves the reader with a sense for Bancroft’s brilliance across a broad range of diverse interests. He paints him as a man who enjoyed the privileges of an education well beyond the norm of his day, and earned by an innate drive and love for scholarship. Nye’s Bancroft was comfortable with life choices that went against the norm, an indication of independent thought. But he was also a man of his times, influenced by the great thinkers of his era and yet contributing one of the most important voices of the nineteenth century. He brought to his generation a better sense of the American story, and to a large degree, popularized history with the first complete treatment of the United States through its inception as a nation. He was guided by a strong belief in divine providence and its hand upon America. But at his core, he was, as depicted by Nye, a scholarly man of letters – a distinction I suspect would have pleased Mr. Bancroft. His legacy is a remarkable body of work sadly forgotten by most citizens of the 21st century because of changing standards in historiography.

Nye does a masterful job of identifying Bancroft’s core beliefs and the influences that formed the man and his career. He also shows a considerable grasp of the nuances of both history and historiography that were in play in the 19thcentury – worth noting because Nye’s training is in literature rather than history. Like all series authors, Nye brings to the work a Ph.D. An English professor at Michigan State University, he might seem like an odd choice to profile a historian, but he proves himself equal to the task, perhaps because biography straddles both history and literature. His obvious mastery of the large collection of papers Bancroft left behind for his biographers is impressive.

Russel Nye was awarded the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for Biography for this work. Is there a better recommendation?

Rene Tyree

American Military University

Photo credit: Einstein at 42 from Wikipedia Commons. Public Domain

If you wrote history in the 19th century….

Russel Nye (1913-1993) provides a glimpse of what was expected of you if you wrote history in the early 19th century in his Pulitzer Prize winning biography of George Bancroft (1800-1891). I thought it worth sharing in that some of my readers are themselves authors of history. Those writing in the 19th century of the events leading up to and surrounding the American Civil War would have been aware of and influenced by these expectations.

- Historians were expected to deal with the history of living men.

Protocols, state papers, and controversies were not the stuff of history. Here Nye draws on the work of Thomas Carlyle (1795-1891)(right) who felt that history was not simply to be “philosophy teaching by experience” but the history of men “with passions in their stomachs, and the idioms, features and vitalities of men.” (146)

“The historian gave the past form and structure, finding dramatic tension, climax, and resolution in chosen episodes and experience. He used quotations and set speeches as a playwright might – allowing ‘the parties,’ as William Hickling Prescott (1796-1859) (image right) said

, ‘not only to act but speak for themselves.'” (147) There had to be opposing forces battling against one another to achieve an effect of conflict. On one side might be the forces of liberty and on the other authoritarianism, popular government against absolutism, civilization versus barbarism, etc.

- Proper historical writing had to have a theme.

A theme bound events together and gave them focus and meaning. This was a quest for the “pervading principle” which was guiding history and flowing beneath the stream of events.

- The historian was to write in the way of an artistic painter.

His work has to be composed and arranged in and artistic, vivid and aesthetically pleasing way like that of a painting. “Historians habitually used such terms as ‘portrait,’ ‘canvas,’ and ‘sketch’; gave careful attention to composition and arrangement of details; and quite deliberately set up ‘scenes’ and ‘tableaux.'” (147) [Image below of painting by Clarence Boyd from University of Kentucky Art Museum: Attacking Indians (or Pilgrims Being Attacked by Indians While at Church), ca. 1880]

- The historian must create in his work a precise sense of place, time and immediacy.

This task was about reconstructing the values and principles and the intellectual and moral atmosphere of the times of which a writer wrote. Bancroft called it ‘the spirit of the age, the impalpable but necessary essence’ of a society.” (148)

Historical writing began to change in the latter part of the 19th century but the points above make for some interesting background for discussion that continues today around academic versus popular history and what appeals to the general reader.

George Bancroft, by Russel B. Nye, (New York: Washington Street Press, Inc., 1960), pp 146-148)

Drawing of Thomas Carlyle fro Wikipedia Commons. Another excellent biography of Thomas Carlyle is available here.

Thomas Carlyle– Project Gutenberg eText 13103

From The Project Gutenberg eBook, Great Britain and Her Queen, by Anne E. Keeling

http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/13103

Book Report: George Bancroft

I realize this won’t be for everyone but I wanted to post the academic book review I finished yesterday on the paperback version of Russel Blaine Nye’s 1945 Pulitzer Prize winning biography George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel. Sadly this book is out-of-print and available only via library or used book markets. It is a fascinating work filled with insights into an uncommon man who was once this country’s most revered historian – but whom most of us have no memory. It also provides considerable information about our country – and indeed the world – in the period leading up to, during and after the Civil War.

It was enlightening to put this post together in that I discovered some great sources of information about many of the people, places and times in which Bancroft lived. Kudos to http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org for their information on important persons in that university’s history.

By Russel B. Nye. New York

(Washington Square Press, Inc.). Pp. 212. 1964. $.60

If biographies written in the twenty-first century tend toward tomes, Russel Nye’s work on George Bancroft, easily the most acclaimed American historian of the nineteenth century, demonstrates how to impress with a modicum of words. Bancroft’s life spanned a period of epic change in the fledgling American nation. Nye skillfully paints a portrait of the man against the sweeping landscape of the United State’s passage from fledgling country at the turn of 18thcentury to a battle-scarred nation ninety years later. Bancroft helped to make American history as politician and statesman. He also became one of the country’s most gifted historiographers and the first popular historian, a title that was, by the end of the century, not unlike his literary writing style, considered “passé.”

George Bancroft came from a legacy of northeastern conservatism. Bred squarely into the center of the American Calvinistic farming culture of Worcester, Massachusetts, his grandfather Samuel Bancroft was both strict Calvinist and independent of mind. Bancroft’s father, Aaron Bancroft, had a noteworthy career as one of the first leaders of the Unitarian movement. This step toward liberalism directed him to the pastorship of a small Second Congregational Church of Worcester and modest means to support his growing family. But it also positioned him with the intellectual elite of New England. The Bancroft home was a place where books were plenty and reading and discussion encouraged. Independent reason was also valued. Aaron Bancroft authored one of the more popular biographies of George Washington, a man who young George Bancroft would eventually count as among the most influential hero-leaders of the country.

George stood out among his siblings and opportunities were given to him to attend preparatory school at a young age even though it caused strain on his father’s finances. He excelled and passed entrance exams to Harvard College at the  age of 13. Bancroft graduated Harvard at 17 and, with the assistance of college president John Thornton Kirkland (pictured right and papers here), w

age of 13. Bancroft graduated Harvard at 17 and, with the assistance of college president John Thornton Kirkland (pictured right and papers here), w as provided both financial support and the necessary letters of introduction to follow a select few Harvard graduates to Göttingen, one of the top universities in Germany (brief history of the town and university here). His goal was to follow his father into the ministry. He began a rigorous course of study including a self-imposed schedule of sixteen hour days. By the age of twenty, Bancroft had a Göttingen doctorate and the respect of some of Germany’s most noted professors. But he had also developed a considerable interest in philosophy, history and literature and began to doubt whether a career in the ministry remained his passion. He continued with post doctorate studies in Berlin and by the end of his four years in Europe had met many of its influential writers, artists and academics. Bancroft returned home filled with ideas about educational reform and exhibiting mannerisms and dress inspired by his time abroad.

as provided both financial support and the necessary letters of introduction to follow a select few Harvard graduates to Göttingen, one of the top universities in Germany (brief history of the town and university here). His goal was to follow his father into the ministry. He began a rigorous course of study including a self-imposed schedule of sixteen hour days. By the age of twenty, Bancroft had a Göttingen doctorate and the respect of some of Germany’s most noted professors. But he had also developed a considerable interest in philosophy, history and literature and began to doubt whether a career in the ministry remained his passion. He continued with post doctorate studies in Berlin and by the end of his four years in Europe had met many of its influential writers, artists and academics. Bancroft returned home filled with ideas about educational reform and exhibiting mannerisms and dress inspired by his time abroad.

Bancroft spent the next several years trying to find his calling. Trained in philology (the study of languages) as well as theology, he tried on the role of Greek tutor at Harvard but became frustrated with the college’s lack of interest in adopting the new educational techniques he brought from abroad. He was also unpopular as a teacher, which is not to say that he was a bad teacher; rather a demanding one. By mutual consent, he left Harvard after a year and with fellow Harvard and Göttingen graduate Joseph Cogswell, opened the Round Hill School for boys near Northampton, Massachusetts in 1823. It became a phenomenon of sorts due to the melding of the latest methods of European educational reform with those of American boarding school. “It was one of the earliest and most successful efforts of the nineteenth century to raise the level of American secondary education by absorbing the new European experimentation, and served as a powerful influence in the diffusion of new ideas on discipline, individual attention, and stimulation of student interest” (45). A student was treated as an individual with unique learning patterns and cooperated as an equal with his teacher rather than as an inferior with his master. Despite the demanding program, the elite of New England clamored to enroll their sons. With Bancroft as the primary teacher and Cogswell managing administration, the school grew in both size and reputation.

It was at Round Hill School that Bancroft met his wife, Sarah Dwight. Her status as the daughter of a wealthy New England family would ensure his financial independence. Bancroft also continued to work on his poetry (he had published Poems while at Harvard) and found opportunity for preaching. But he was successful at neither. His poetry was labeled amateurish and his oration at the pulpit “too consciously learned, too pretentiously oratorical” (5). Interestingly, Bancroft would become a gifted literary critic. A man of many interests, he became bored with the life of a country school teacher and bowed out of the venture in 1831. The Round Hill School failed three years later.

Bancroft discovered while at Round Hill a growing interest in politics. He began to write for prominent journals and even spoke in a political forum in Northampton at the behest of town leaders. In 1830 he was nominated for the Massachusetts’s senate by the Workingmen’s party. Although he declined, his voice as a political philosopher began to emerge. It was firmly centered on the premise that the will of the many outweighed that of the few, a principle that he considered foundational to democracy. He clearly identified himself as a Jacksonian democrat in 1836, a fact that surprised a number of his Whig Harvard colleague s including friend Edward Everett (pictured right). His allegiance was with the common, agrarian masses rather than the privileged minority. His political position became all the more public with Bancroft’s growing involvement in the Democratic Party. He wrote several journal articles in support of Jackson’s position on the national banking issue which he attributed to the long struggle between capitalists and laborers. In 1838, his party work was rewarded with the position of Collector of the Port of Boston. By 1844, he was a prominent player in the Massachusetts democratic delegation and played a key role in securing the Presidential nomination for

s including friend Edward Everett (pictured right). His allegiance was with the common, agrarian masses rather than the privileged minority. His political position became all the more public with Bancroft’s growing involvement in the Democratic Party. He wrote several journal articles in support of Jackson’s position on the national banking issue which he attributed to the long struggle between capitalists and laborers. In 1838, his party work was rewarded with the position of Collector of the Port of Boston. By 1844, he was a prominent player in the Massachusetts democratic delegation and played a key role in securing the Presidential nomination for  James K. Polk (pictured left). Polk appointed Bancroft Secretary of the Navy the following year and he found himself Acting Secretary of War during the months that opened the Mexican War. But Bancroft was after a diplomatic post and between 1846 and 1849 he served as United States Minister to England. It was during this time that he amassed a huge collection of historical notes from British archives, utilizing scribes and secretaries to copy copious amounts of data. These he brought home to America for use in future historical writing.

James K. Polk (pictured left). Polk appointed Bancroft Secretary of the Navy the following year and he found himself Acting Secretary of War during the months that opened the Mexican War. But Bancroft was after a diplomatic post and between 1846 and 1849 he served as United States Minister to England. It was during this time that he amassed a huge collection of historical notes from British archives, utilizing scribes and secretaries to copy copious amounts of data. These he brought home to America for use in future historical writing.

The scholar in Bancroft had found new voice shortly after leaving Round Hill. In 1834, he published the first of what would become his multi-volume treatise, A History of the United States from the Discovery of the Continent (set of all volumes to right). (A full listing of Bancroft’s works avail able online can be found here.) He chose to focus not on contemporary history but rather on the formation and evolution of the nation. Bancroft believed that the creation of the United States of America was part of a divine plan. It was a demonstration for all the world of the efficacy of a nation built on the principles of liberty.

able online can be found here.) He chose to focus not on contemporary history but rather on the formation and evolution of the nation. Bancroft believed that the creation of the United States of America was part of a divine plan. It was a demonstration for all the world of the efficacy of a nation built on the principles of liberty.

Pivotal to the country’s success was the quality of its leaders. “The secret of the science of governing, Bancroft decided, lay in the quality of a nation’s leaders – those great men who personify the people’s ideals, act out their interests, and crystallize their needs in laws and institutions” (82). Nye found that Bancroft valued two types of hero-leaders. The first was the agrarian nobleman best exemplified in Andrew Jackson (pictured below).

His gift was an innate perceptiveness gained from long connection with nature. The second was the classic wise man whose traits Bancroft found in George Washington, a man for whom he had a lifelong admiration.

Abraham Lincoln eventually became Bancroft’s third hero-leader. While initially unimpressed with Lincoln, his respect for him grew to such a degree that he eventually thought him representative of the genius of the American people. Bancroft’s regard for Lincoln was no doubt one reason that he was chosen by Congress to deliver his eulogy. It was considered his best oration.

Like the nation, Bancroft had to come to terms with slavery. He blamed the English for its introduction to the colonies and thought it a temporary evil gone array. Its conflict with the principles of liberty was always obvious. While never a flaming abolitionist, Bancroft considered slavery the primary cause of the Civil War and spoke out about it primarily in his writing. He was a resolute unionist and had little sympathy for arguments for state rights and for the succession movement.

Bancroft happily finished his diplomatic career in Germany where he became a favorite of politicians and intellectuals. He returned to a quite life, still writing and active for most of his ninety-one years. The portrait below was painted while Bancroft was in diplomatic residence in Germany.

Nye does a masterful job of identifying Bancroft’s core beliefs and the influences that formed the man and his career. He also shows a considerable grasp of the nuances of history that were in play in the 19th century, worth noting because Nye’s training is in literature rather than history. His obvious mastery of the large collection of papers Bancroft left behind for his biographers is impressive.

Nye leaves the reader with a sense for the utter brilliance of Bancroft (pictured below in his study) and yet presents him as anything but infallible. He was a man who enjoyed the privileges of an education well beyond the norm of his day and earned by an innate drive and love for scholarship. He was comfortable with life choices that went ag ainst the norm, an indication of independence of thought. He was not unfamiliar with loss, having endured the death of his young wife. He knew failure, having disappointed those who saw in him potential as minister. His failure as a poet, a personal aspiration, revealed a level of sensitivity (He worked very hard to find and destroy every copy of his Poems.). He embraced cultures and perspectives outside of his own and yet remained an American patriot. He brought to his generation a better sense of the story of their country and to a large degree, popularized history. He remained a loud voice for the ideals of liberty and democracy and the rights and privileges of the masses. But at his core, he was, as depicted by Nye, a man of letters and I suspect that Mr. Bancroft would be pleased with that distinction. His legacy is a remarkable body of work sadly forgotten by most citizens of the 21st century.

ainst the norm, an indication of independence of thought. He was not unfamiliar with loss, having endured the death of his young wife. He knew failure, having disappointed those who saw in him potential as minister. His failure as a poet, a personal aspiration, revealed a level of sensitivity (He worked very hard to find and destroy every copy of his Poems.). He embraced cultures and perspectives outside of his own and yet remained an American patriot. He brought to his generation a better sense of the story of their country and to a large degree, popularized history. He remained a loud voice for the ideals of liberty and democracy and the rights and privileges of the masses. But at his core, he was, as depicted by Nye, a man of letters and I suspect that Mr. Bancroft would be pleased with that distinction. His legacy is a remarkable body of work sadly forgotten by most citizens of the 21st century.

American Military University

Rene Tyree

Good Discussion on the Inevitability of the Civil War

The final post of my series Exploring Causes of the Civil War (which you can read here) titled “The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability,” has spawned some interesting debate over both the inevitability of the Civil War and the idea of “inevitability” itself. Blogger Elektratig not only provides some insightful comments to my post, but expounds upon those in a post titled “Historical Inevitability” on his own blog here. He provides a good argument that rather than “inevitability,” we should speak of “probability.”

John Maass (a fellow wordpress.com blogger at A Student of History) enters the discussion with the assertion that looking at historical events as “inevitable” is amateurish history (see comments on both my original post and on Elektratig’s) and is particularly dangerous in the field of military history because of the contingencies that can come into play during war.

It promotes a teleological view of history that is simply far too unsophisticated and “cookie cutter” for an accurate look at the past. Anyone can go back into the chronicle of the past and see lots of events and add them all up to “prove” that a subsequent event was inevitable or foreordained. Historians don’t do this, or at least they shouldn’t.

“Teleologic” comes from the noun “teleology” which has to do in the philosophical sense (as I believe John intended it) with the explanation of phenomena by the purpose they serve rather than by postulated causes. In the theological sense, it refers to the doctrine of design and purpose in the material world.i

Both meanings I find interesting in that, as I mentioned in my last post, I’m preparing a research proposal to study the impact of historian George Bancroft on 19th century historiography. Bancroft has been criticized for his views about America’s destiny being pre-ordained. Frank Freidel captured it well in his work, The Golden Age of American History.

Both meanings I find interesting in that, as I mentioned in my last post, I’m preparing a research proposal to study the impact of historian George Bancroft on 19th century historiography. Bancroft has been criticized for his views about America’s destiny being pre-ordained. Frank Freidel captured it well in his work, The Golden Age of American History.

Bancroft saw a divine shaping of American destinies, from the founding of the individual colonies through the successful culmination of the struggle for independence, and beyond to his own day. He wrote in his preface in 1834, “It is the object of the present work to explain how the change in the condition of our land has been brought about; and, as the fortunes of a nation are not under the control of blind destiny, to follow the steps by which a favoring Providence, calling our institutions into being, has conducted the country to its present happiness and glory.”ii

As the new “scientific history” began to emerge, this position received considerable challenge.

My thanks to both commenter’s for their excellent discussion.

Photo above of Creation of the Sun and Moonby Michelangelo, face detail of God. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

i Oxford Pocket American Dictionary of Current English, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 835.

iiFrank Freidel, The Golden Age of American History [book on-line] (New York: G. Braziller, 1959, accessed 30 December 2007), 70; available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=4419028; Internet.

American Historian: George Bancroft

I’m back from Christmas break and trying to recuperate from a few too many cinnamon rolls. Reading assignments and preparation of a research proposal due Sunday are top of mind.

The class is Historiography so the research isn’t to be about the development and proof of a thesis. It’s more about research into the history of how history was written.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

Bancroft was one of the best known American historians of the 19thcentury. While Harvard educated (he entered at 13 and graduated at 17!), he is considered a “literary historian,” who wrote in a style popular with  the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

Perhaps less known is that Bancroft, while Secretary of the Navy, created the Naval Academy. He was also chosen by Congress to eulogize Abraham Lincoln. The New York Times reprinted that Eulogy on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the event in 1915. It, along with drawings of the event, can be seen in their entirety here.

I have located the index to his papers housed on microfiche at Cornell University and two biographies which leverage that material. The first, a two volume set 1971 reprint of M.A. DeWolfe Howe’s 1908 work The Life and Letters of George Bancroft, I was able to find on the Amazon Marketplace in almost pristine shape. The second, George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel, was written by Russel B. Nye and published in 1945. It’s on order. There are other large collections of Bancroft materials in holdings by the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. I’m beginning in earnest a search for articles that deal with his contributions to American history as well.

As a follow-up at some later point, I think it would be very interesting to contrast the style and impact  of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

You might recall that Charles and Mary Beard were the first to suggest that the Civil War was the second American revolution as was mentioned in my previous post here.

The exceptional oil on canvas portrait above of Bancroft in later life was painted by Gustav Richter, a German painter (1823 – 1884). It is a part of the Harvard University Portrait Collection and is on display at Memorial Hall.

More as I get into my research.

Photo credits:

Photo of George Bancroft in middle age taken by Mathew Brady, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo of painting above: The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

On Historiography and Roman Civil War

I mentioned in an earlier post that I’m taking a course in Historiography this term. I’m heavily into Ernst Breisach’s Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern.

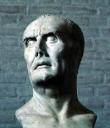

I mentioned in an earlier post that I’m taking a course in Historiography this term. I’m heavily into Ernst Breisach’s Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. So far, the focus has been on the emergence of Greek and Roman historiography and I have a small essay contrasting the two due this weekend. This is the kind of reading that “wets your whistle” (do people still say that?). We are given a glimpse of the broad picture – a sweeping brush across the centuries before the birth of Christ as men began slowly to understand the value of recorded history and commentary. But we are also introduced to bits of information that are hard to not pursue further. Case in point – a Roman civil war that occurred between 88 and 82 B.C. It was fought between the populares (“favoring people”) under Gaius Marius and the optimates (“the best of men”) under Lucius Cornelius Sulla.i

So far, the focus has been on the emergence of Greek and Roman historiography and I have a small essay contrasting the two due this weekend. This is the kind of reading that “wets your whistle” (do people still say that?). We are given a glimpse of the broad picture – a sweeping brush across the centuries before the birth of Christ as men began slowly to understand the value of recorded history and commentary. But we are also introduced to bits of information that are hard to not pursue further. Case in point – a Roman civil war that occurred between 88 and 82 B.C. It was fought between the populares (“favoring people”) under Gaius Marius and the optimates (“the best of men”) under Lucius Cornelius Sulla.i

Romans killed and exiled Romans on a large scale. The Republic lived on as a mere shell in which the ambitions of men like Sulla, Pompey, and eventually Caesar governed events, often to the detriment of the Republic. For the first time Romans became aware that their life differed greatly from that of their ancestors and that the continuity of Roman tradition had been broken. That experience proved extremely disturbing. How did the past, seen as glorious and ideal, fit with the troubled present? Historical and quasi-historical works were written under the spell of this question.ii

What were the issues over which the bloodbath occurred?

-

Land reform

-

The grasping for political power between factions supporting democratic versus republican ideals, and

-

Class disputes.

Hmmm…. I’ll let you draw your own parallels to our own Civil War.

Of interest, it was Gaius Marius (left) who reformed the Roman Legion by turning it into a professional army open to men of any class. Volunteers signed up for twenty years and the promise of a pension (land grant) and spoils. Soldiering as a profession was born. The allegiance of the legionnaire shifted from country to commanding general as the awarding of a pension was dependent upon the persuasiveness of the general (not by law).

Of interest, it was Gaius Marius (left) who reformed the Roman Legion by turning it into a professional army open to men of any class. Volunteers signed up for twenty years and the promise of a pension (land grant) and spoils. Soldiering as a profession was born. The allegiance of the legionnaire shifted from country to commanding general as the awarding of a pension was dependent upon the persuasiveness of the general (not by law).

I’ll be adding several links to ancient military history…. including several sections in Bill Thayer’s LacusCurtius (good primary sources like Polybius: The Histories). He has also transcribed to the web The Histories of Appian which chronicle the Appian Civil Wars.

Rene

i, ii Breisach, Ernst. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, 2nd Edition. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 52.