Posts Tagged ‘James McPherson’

OUP Blogs Lincoln as Part of Bicentennial Celebration

I’m a fan of university presses so I’m sharing some information forwarded to me by the good folks at Oxford University Press about books and stories they are featuring on their Oxford University Press USA Blog as part of the Lincoln Bicentennial celebration. Check it out.

- An excerpt from James McPherson’s ABRAHAM LINCOLN

- A series of FAQ’s with Allen Guelzo author of LINCOLN: A Very Short Introduction

- A look at how Lincoln almost failed by Jennifer Weber author of COPPERHEADS: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln’s Opponents in the North

- A post by Lincoln Prize Winner Craig L. Symonds comparing Lincoln and Obama which you can view here.

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 5

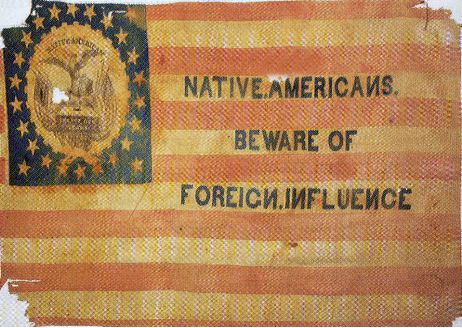

Flag of the Know Nothing Party

Historian James McPherson points out that the membership in the Know Nothings was “drawn primarily from young men in white-collar and skilled blue-collar occupations. A good many of them were new voters. One analysis showed that men in their twenties were twice as likely to vote Know Nothing as men over thirty.” (1)

Their leaders were also “new men” in politics who reflected the social backgrounds of their constituency. In Pittsburg, more than half of the Know-Nothing leaders were under thirty-five and nearly half were artisans and clerks. Know Nothings elected to the Massachusetts legislature in 1854 consisted mainly of skilled workers, rural clergymen, and clerks in various enterprises. Maryland’s leaders were younger and less affluent than their Democratic counterparts.” (1)

For more information on the Know Nothing Party in Massachusetts, see the Massachusetts Historical Society here.

(1) Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States), (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 135-136.

Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States), (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 135-136.

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 2

In the 1830s and 1840s, Americans had rediscovered a fascination with fraternalism discarded earlier in the century “when anti-Masonry led to public suspicion of secret societies.” (1) This was the era of the Odd Fellows, the Foresters, the Good Fellows and the Druids, the Red Men and the Heptasops. (2)

James McPherson marks the beginning of the movement that would lead to the “Know Nothing” American Party in the 1840s, when nativist parties flared and then cooled after the elections of 1844. (3) Relief from depression calmed tensions between native and foreign-born workers just in time for the massive influx of Europeans that resulted from that continent’s potato blight. (4) But American nativist sentiments continue to simmer and “on a late December evening in 1844, thirteen men gathered in the home of printer Russell C. Root in New York City” to form a group calling itself the American Brotherhood. The name was eventually changed to “Order of United Americans (OUA).” Its goals, outlined in a “code of principles,” were “to release our country from the thralldom of foreign domination.” This marked the birth of a nativist fraternity…and formed the nucleus of a far larger nativist effort than ever before. (5)

Membership in the Order of United Americans was limited to white men, twenty-one years of age or older, native born and Protestant. Its leaders were reasonably affluent and good organizers albeit from the “margins of the establishment.” This was a secret society replete with mysterious rituals and procedures that gave it an “illusion of antiquity.” (6)

Central to its structure was the magical triad. There were three levels of authority (local chapter, state chancery, and national archchancery), three chancellors sent from chapter to chancery, three archchancellors sent on to national. But there was only one leader of the OUA (limited to a single year term) and in the language of the lodge vogue he was called the arch grand sachem. By 1850, he ruled over a truly national domain with groups in New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Missouri, and Ohio. (6)

Gradually the organization began to become politicized and attracted “many conservative Whigs whose nativist ideology conveniently intersected with political needs in a time of party disarray.” (7)

—

1. David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 106.

2. Ibid.

3. James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 130.

4. Ibid.

5. David H. Bennett, The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History, 105.

6. Ibid, 107.

7. Ibid., 110.

New Arrival – Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief

This week I received a review copy of James M. McPherson’s new work, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief from the good folks at Penguin Press. Needless to say, I’m very much looking forward to diving in as Dr. McPherson’s books on Lincoln remain among my favorites.

He opens the book with the following.

“The insurgent leader…does not attempt to deceive us. He affords us no excuse to deceive ourselves. He can not voluntarily reaccept the Union; we can not voluntarily yield it. Between him and us the issue is distinct, simple, and inflexible. It is an issue which can only be tried by war and decided by victory.”

—Lincoln’s annual message to Congress,

December 6, 1864

Tried by War

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief

James M. McPherson – Author

Hardcover | 6.14 x 9.25in | 384 pages | ISBN 9781594201912 | 07 Oct 2008 | The Penguin Press

Rotov on Suffering

Catching up on my reading, I found Dimitri Rotov’s post [here] on Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering to be  insightful. Follow his links to his previous posts as well. He suggests that Faust may step in for James McPherson as leading Civil War historian. While I gather he isn’t a fan of the latter, he seems to be of the former. I look forward to his upcoming review.

insightful. Follow his links to his previous posts as well. He suggests that Faust may step in for James McPherson as leading Civil War historian. While I gather he isn’t a fan of the latter, he seems to be of the former. I look forward to his upcoming review.

You may recall that I mentioned receiving Faust’s book in my posting here. It’s near the top of my review list.

For more information on Faust and McPherson, see my the historians page here.

Were the North and South Evenly Matched…on the Rails?

One of the questions that was much debated in class was whether the North and South were evenly matched in the American Civil War? To get the discussion rolling, our professor threw out the following…

In his interesting study of the American Civil War, Archer Jones argues in Civil War Command and Strategy: The Process of Victory and Defeat (1992), that despite its superior numbers, the Union advantage was greatly diminished by the extent of Southern territory, the intrinsic superiority of the defense over the offense, and the problems of supplying armies over long distances. Jones also states that Northern industrial dominance also proved almost useless in a war that depended less on complex weaponry and ammunition than on the man with the rifle. In Jones’ opinion, the two sides were, in fact, almost evenly matched.[i]

Our task was to take a stand on whether the North and South were evenly matched. I decided to focus on the very specific area of railroad transportation during the war. Part of my interest in this area comes from my association with friend and rail historian Peter A. Hansen, the editor of Railroad History and author of a number of articles for Trains Magazine. I was able to interview him on the topic and have included a good part of that in the post below. The photo below will be included in the upcoming issue of Railroad History which “is given over to a nearly-encyclopedic overview of every company that ever built steam locomotives in America.”[ii] The principal contributor is John H. White, Jr., former curator of transportation at the Smithsonian Institution.

Photo: New Jersey Locomotive & Machine-built 4-4-0 Fred Leach near Union Mills, Va., on August 1, 1863, the year after it was built. Its stack and tender have taken cannon shot, and the main rod is missing. It became Orange and Alexandria Warrenton after the American Civil War. Library of Congress: 111-B-185.

Charles Roland, in his book An American Illiad: The Story of the Civil War, provides a strong case for the American Civil War being considered the “first complete railroad war.” He asserted that the North was well ahead of the South in railroad resources entering into the war with 20,000 miles of rails in 1860 to the South’s 10,000. The railroads of the north were better “linked into systems of trunk lines that covered the entire region.”[iii] There were other things that made the North’s railroads superior. “First, it was dotted with locomotive factories, concentrated particularly in Massachusetts, Paterson, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. All of them remained beyond the reach of Rebel forces, so production was never disrupted. It was never disrupted for want of materials, either, since most of the iron ore and coal were also concentrated in the North.”[iv]

“In addition, the North’s railroads were almost all built to the standard track gauge of 4’ 8 ½”. That meant the cars could be interchanged from one line to another without the need for time-consuming unloading and reloading of passengers and freight. In the South, the rail network was pretty thin to begin with, and the multiplicity of track gauges hampered operations even more. That was particularly important considering that most of the war was fought on Southern soil. With the notable exception of one shining moment at the First Battle of Bull Run, the South was never consistently able to rush men and materiel to the front by rail. There were just too many obstacles to such smooth operation in most of Dixie.”[v]

Photo above: Station at Hanover Junction, Pa., showing an engine and cars. In November 1863 Lincoln had to change trains at this point to dedicate the Gettysburg Battlefield. LOC: 111-B- 83.

Photo below: The four-tiered, 780-foot-long railroad trestle bridge built by Federal engineers at Whiteside, Tenn., 1864. A guard camp is also shown. Photographed by George N. Barnard. LOC: 111-B-482.

“It’s a little-known fact, but track gauge was the first big standardization issue – in any industry. It seems incredible to us from our modern perspective, but many people were slow to grasp the need for standardization. It had never been needed in the days when every village had its own blacksmith or carpenter, whose products never needed to be used in conjunction with those of the smithy or carpenter in the next town.”[vi]

Photo above: Tredegar Iron Works. Artist: Alexander Gardener, Public Domain, Wikipedia Commons.

“The South didn’t have a single locomotive factory of any consequence during the Civil War. Several had made a start during the 1840s and 1850s but failed to survive into the War years – including Richmond’s famous Tredegar Iron Works (see the American Civil War Center’s site at Tredegar Iron Works here). While the firm itself survived until 1956, they produced locomotives only from 1851 to 1860. Even as the storm clouds were gathering, they decided in late 1860 that the locomotive business wasn’t profitable for them, and they retooled the shop for other uses.

“[vii]

Photo right (cropped): James Noble Sr. from www.civilwarartillery.com/manufacturers.htm.

“Aside from Tredegar, the only wartime Southern locomotive factory that’s even marginally worth mentioning was James Noble and Son of Rome, Georgia. They produced only a few locomotives after 1855 and their factory was destroyed by Sherman’s army in 1864. What this means, of course, is that Southern railroads became increasingly dysfunctional as their locomotives were destroyed, since they had no means of replacing them. It also meant that their remaining locomotives were often old, and/or held together by any means possible.”[viii]

McPherson substantiates this in his book, Battle Cry of Freedom. He indicates that of the 470 locomotives built in the U.S. in 1860; only 19 were built in the South.[ix] According to Hansen, “the production of 470 locomotives in a single year may seem like a large number. But it is less surprising in light of two things. First, railroad mileage in the U.S. had surpassed 30,000, and about 2/3 of that total had been built in the previous decade. Just like new highways today, there was comparatively little traffic on new lines in their first couple of years, but usage mushroomed when people and businesses began to change their previous transportation preferences, and when businesses began to locate along the new lines. When a line began to see more traffic, whether two or five or eight years after it was built, new locomotives were needed to handle it. An economist might say that the need for rolling stock lagged the actual construction by a few years.”[x]

“Another thing to consider is the poor utilization of assets in those days. Just as standardization was a new concept in the middle of the 19th century, so, too, was asset utilization. The latter concept is quite recent indeed, not being fully understood until just the past decade or so. [Note: Consider that Southwest Airlines ran circles around its competitors for years, chiefly because SWA insisted on having an entire fleet of identical planes, and on keeping them on the ground for only 30 minutes at each stop. The underlying rationale for both policies was better asset utilization. The older airlines are still struggling to apply those same lessons.] A steam engine is a highly labor-intensive beast. It requires constant attention from fireman and engineer alike in order to get maximum productivity while it’s working, and it spends about two hours in the shop for every hour it spends on the road. That time is absolutely necessary to the proper functioning of the machine, since grates need to be shaken, ashes need to be dumped, and moving parts need lubrication. (Tallow was a common valve lubricant in those days before petroleum engineering, and applications had to be repeated frequently.) About once a month, the steam engine’s fire was dumped altogether so the tubes and flues could be inspected. The process of cooling an engine down, inspecting it, and firing it back up typically took 24-48 hours, so there’s a big chunk of unproductive time right there. So the bottom line is that they needed a lot of locomotives in those days!”[xi]

Brilliant Uses of Railroads

The South did have some success with the use of trains for troop transfer. Johnston’s use of the Manassas Gap Railroad to move his troops to Manassas Junction to reinforce Beauregard was brilliant and no doubt influenced the outcome of that engagement which so demoralized the North. Roland also reviews Bragg’s “almost incredible strategic use of the railroads” against Buell as the latter approached Chattanooga. “The Confederates half-circled the Union army by moving 30,000 from Tupelo, Mississippi, roundabout by way of Mobile and Atlanta to Chattanooga, a movement of some 776 miles.”[xii] Hansen felt that, “while it was true that Bragg’s campaign was a remarkable success in the face of daunting logistics, this was the exception that proves the rule.” The mere fact that he had to detour 776 miles in order to go 300 speaks to the paucity of railroads in the South. And even in his 776-mile detour, he had to port his troops on foot east of Montgomery, where the railroad ended, before he could load them on trains again near Columbus, Georgia. So yes, the railroads helped him win, but I submit that it was his audacity, combined with Buell’s dithering, that gave him the ability to make the best of a questionable asset.”[xiii]

Hansen added, that “it is worth noting that railroads were the whole reason Chattanooga had such strategic significance. The principal line from Richmond to Atlanta, and the line from Memphis to the east, converged there. Without Chattanooga, the South’s ability to move men and materiel by rail in their own territory was all but gone.”[xiv]

Thomas Ziek, Jr. came to the same general conclusion in his Master’s Thesis, “The Effects of Southern Railroads on Interior Lines during the Civil War.” He tried to determine whether or not the South enjoyed the advantage of interior lines and concluded that they did not.

The use of railroads during this conflict placed an enormous physical strain upon the limited industrial resources of the Confederacy, and a great strain upon the intellectual agility of the Confederate High Command. Based upon the evidence studied, and the time-space comparisons of both Northern and Southern railway operations, several conclusions can be drawn: the South entered the war with a rail system that was unable to meet the demands of modern war; the Confederate leadership understood the importance of the railroad and its importance to strategic operations early in the war, but were unwilling to adopt a course of action that best utilized their scarce assets; Union control, maintenance, and organization of its railway assets ensured that it would be able to move large numbers of troops at the strategic level efficiently from early 1863 to the end of the war. Based on these conclusions, the Confederacy lost the ability to shift troops on the strategic level more rapidly than the Union by 1863. This was a result of its physically weakened railroad system and military setbacks which caused Southern railroads to move forces over longer distances.[xv]

My conclusion, for this area of focus, is that the North and South were NOT equally matched either in their physical rail assets nor in their management of those assets. While the South had some moments of brilliance in their use of railroads, they simply did not have the infrastructure to maintain, let alone expand, the railroads of their region to their greatest advantage.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i] White, Charles, AMU CW500.

[ii, iv, v, vi, vii, viii, x, xi, xiii, xiv] Hansen, Peter A., Personal interview. Sept. 9, 2007

[iii, xii] Roland, Charles P. An American Iliad: The Story of the Civil War

[ix] McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom

[xv] Ziek, Thomas G., Jr., “The Effects of Southern Railroads on Interior Lines During the Civil War.” A Master’s Thesis.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, and Part IV: The Antebellum North.

___________________

Sectional disputes rose and ebbed numerous times in the years before the war. Modernization created social tensions ![]() because, as pointed out by James McPherson, “not all groups in American society participated equally in the modernizing process or accepted the values that promoted it. The most important dissenters were found in the South.”[i] The South’s failure to modernize was perceived by many of her citizens as actually desirable.

because, as pointed out by James McPherson, “not all groups in American society participated equally in the modernizing process or accepted the values that promoted it. The most important dissenters were found in the South.”[i] The South’s failure to modernize was perceived by many of her citizens as actually desirable.

Sectional arguments expanded to include topics like internal improvements, tariffs, and whether expansion west and south would upset the parity between free and slave states. Foundational to the latter was the belief on the part of the slaveholder in their right to a slave-based social order and a need for assurances of its continuity. Equal representation in government was perceived as critical to that goal.

The rise of abolitionism – largely in the North – put the proponents of slavery on the defensive. The formation of the American Anti-Slavery Society marked the beginning of militant abolitionism and an unprecedented crusade that would rival any modern national marketing campaign. Barbed attacks against slaveholding southerners were launched. They were called the great enemies of democracy and flagrant sinners.[ii] The anti-slavery crusade thus became both a moral one and imperative for the preservation of democracy. Abolitionists created in a section’s consciousness the belief in a “Slave Power.”[iii] Historian Avery Craven suggests that when politicians successfully linked expansion and slavery, the Christian masses accepted as de facto the Abolition attitudes toward both the South and slavery.[iv] Civil war, he contends, “was then in the making.”[v]

The pro-slavery faction fought back with their own “sweeping ideological counterattack that took the form of an assertion that slavery, far from being a necessary evil, was in fact a ‘positive good.’”[vi] “The section developed a siege mentality; unity in the face of external attack and vigilance against the internal threat of slave insurrections became mandatory.”[vii] To insulate itself from the influence of the anti-slavery North, some in the South called for its citizens to shun Northern magazines and books and refrain from sending young men to northern colleges.

The pro-slavery faction fought back with their own “sweeping ideological counterattack that took the form of an assertion that slavery, far from being a necessary evil, was in fact a ‘positive good.’”[vi] “The section developed a siege mentality; unity in the face of external attack and vigilance against the internal threat of slave insurrections became mandatory.”[vii] To insulate itself from the influence of the anti-slavery North, some in the South called for its citizens to shun Northern magazines and books and refrain from sending young men to northern colleges.

The debate over slavery thus infiltrated politics, economics, religion and social policy. Not surprisingly, those who felt most threatened began to speak more loudly of secession.

Next post: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity

© 2007 Rene Tyree

Images:

Library of Congress: The African-American Mosaic.

“Declaration of the Anti-Slavery Convention Assembled in Philadelphia, December 4, 1833” R[ueben] S. Gilbert, Illustrator Philadelphia: Merrihew & Gunn, 1833 Broadside Rare Book and Special Collections Division

“Anthony Burns” Boston: R.M. Edwards, 1855 Broadside Prints and Photographs Division

____________________

[i] James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 22.

[ii] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 150.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 51-52.

[vii] Ibid., 52.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part III – The Antebellum South

The Southern man aspired to a lifestyle that had, as utopian model of success, the English country farmer. Jeffersonian agrarianism was valued over Hamiltonian industrialization.

To achieve success, cheap labor in the form of slavery was embraced. The capital of the south was invested in slaves even after modernized farming equipment became available. More land was needed to produce more crops which required, in turn, more slaves. This cycle repeated until some 4 million slaves populated the South by mid-century. The system became self-perpetuating because – as posited by historian James McPherson – slavery undermined the work-ethic of both slave and Southern whites. The slave obviously had limited opportunity for advancement. Manual labor became associated with bondage and so lacked honor. The result was a limited flow of white immigrants to the south who could provide an alternative labor force and an increase in the migration of southern whites to free states.[i]

became associated with bondage and so lacked honor. The result was a limited flow of white immigrants to the south who could provide an alternative labor force and an increase in the migration of southern whites to free states.[i]

Simply stated, the South chose not to modernize. It hosted little manufacturing. It also lacked a well developed transportation system (a fact that would prove key to the conduct of the war).

White supremacy was simply a fact. Part of the responsibility of owning slaves was to care for their material needs as you would children. White southern children grew up with a facility for “command” and became a part of what was viewed by many as a southern aristocracy.[ii]

According to historian Avery Craven, “three great forces always worked toward a common Southern pattern. They were:

- a rural way of life capped by an English gentleman ideal,

- a climate in part more mellow than other sections enjoyed, and

- the presence of the Negro race in quantity. More than any other forces these things made the South Southern.”[iii]

Next post – The Antebellum North

For additional reading…

On Jeffersononian Agrarianism see the University of Virginia site here.

[i] James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 10., 41.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 33.

Photo Credits:

Watercolor View of the West Front of Monticello and Garden (1825) by Jane Braddick. Peticolas. The children are Thomas Jefferson’s grandchildren. Public Domain [Source: Wikipedia Commons]

Inspection and Sale of a Slave. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Digital ID: cph 3a17639 Source: b&w film copy neg.

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-15392 (b&w film copy neg.)

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part II – Antebellum America

In the last post, I kicked off a series looking at the causes of the American Civil War. Study of 19th century Antebellum America reveals a young country experiencing incredible change. Its rate of growth in almost all measures was unrivaled in the world. Its population was exploding through both immigration and birth rate. The push for land drove expansion of its boundaries to the south and west. Technological development enabled modernization and industrialization. The “American System of Manufactures” created the factory system.[i] People became “consumers” rather than “producers” of goods and this changed many social aspects of society.

The majority of Americans held a Calvinist belief structure. Puritan influence was strongest in New England. Immigration of large numbers of Catholic Irish created new cultural and ethnic tension. Irish Catholics tended to oppose reform and clustered in the lower classes of the North while native Yankee Protestants predominated in the upper and middle-classes.[ii] The century was marked by enthusiastic evangelical reformation movements. [Note: Jonathan D. Sassi has a concise description of the antebellum evangelical reformation movement in America here.]

A two-party political system had emerged by 1830. “Issues associated with modernizing developments in the first half of the century helped to define the ideological position of the two parties and the constituencies to which they appealed.”[iii]  Democrats inherited the Jeffersonian commitment to states’ rights, limited government, traditional economic arrangements, and religious pluralism; Whigs inherited the Federalist belief in nationalism, a strong government, economic innovation, and cultural homogeneity under the auspices of established Protestant denominations.[iv]

Democrats inherited the Jeffersonian commitment to states’ rights, limited government, traditional economic arrangements, and religious pluralism; Whigs inherited the Federalist belief in nationalism, a strong government, economic innovation, and cultural homogeneity under the auspices of established Protestant denominations.[iv]

The fight for democracy and the fight for morality became one and the same.[v] “The kingdom of heaven on earth was a part of the American political purpose. The Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Scriptures were all in accord.”[vi]

Distinct Northern and Southern cultures began to emerge early in the country’s history. These differences became more marked as the pressures that accompanied the nation’s incredible growth, territorial expansion and social change manifested themselves. Sectional identities and allegiances became increasingly important.

Next post – the Antebellum South.

Photo Above: Th. Jefferson, photomechanical print, created/published [between 1890 and 1940(?)]. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Presidential File. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-2474. This print is a reproduction of the 1805 Rembrandt Peale painting of Thomas Jefferson held by the New-York Historical Society.

For further reading:

- Jonathan D. Sassi has a concise description of the antebellum evangelical reformation movement in America here.]

- I recommend Puritanism in New England written by Donna M. Campbell and accessible on the Washington State University site here.

- James M. McPherson’s Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction has an excellent review of Antebellum America.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i] Historian James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 10, [ii] Ibid., 23, [iii] Ibid., 25, [iv] Ibid., [v] Ibid., 13, [vi] Ibid.

The Civil War as Revolution – Part V

[Note: This post continues a series on The Civil War as Revolution which is available at the following links: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

————-

In the last post, I discussed challenges to the revolutionary nature of the American Civil War by historical revisionists. A second challenge was made by historical economists who contended that the Civil War caused an economic slowdown, not acceleration. Historian James McPherson counters that it is inappropriate to examine the economics of the country as a whole during the war because it so utterly devastated the economic resources of the south. He posits that the North saw economic growth during the war and that “after the war the national economy grew at the fastest rate of the century for a couple of decades, a growth that represented a catching-up process from the lag of the 1860s caused by the war’s impact on the South.”[i]

In the last post, I discussed challenges to the revolutionary nature of the American Civil War by historical revisionists. A second challenge was made by historical economists who contended that the Civil War caused an economic slowdown, not acceleration. Historian James McPherson counters that it is inappropriate to examine the economics of the country as a whole during the war because it so utterly devastated the economic resources of the south. He posits that the North saw economic growth during the war and that “after the war the national economy grew at the fastest rate of the century for a couple of decades, a growth that represented a catching-up process from the lag of the 1860s caused by the war’s impact on the South.”[i]

The third challenge to the Civil War as revolution addressed the plight of Southern blacks and contested that they saw little or no change in their circumstances after both emancipation and the Southern surrender.

Some argued that the Republican Party’s commitment to equal rights for freed slaves was superficial, flawed by racism, only partly implemented, and quickly abandoned. Other

historians maintained that the policies of the Union occupation army, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the national government operated in the interests of the white landowners rather than the black freedmen, and that they were designed to preserve a docile, dependent, cheap labor force in the South rather than to encourage a revolutionary transformation of land tenure and economic status. And finally another group of scholars asserted that the domination of the southern economy by the old planter class continued unbroken after the Civil War.[ii]

But McPherson considers these arguments flawed suggesting that they reflect “presentism,” “…a tendency to read history backwards, measuring change over time from the point of arrival rather than the point of departure.”[iii] He points out that dramatic change did occur and the statistics prove it out. “When slavery was abolished, about 90 percent of the black population was illiterate. By 1880 the rate of black illiteracy had been reduced to 70 percent, and by 1900 to less than 50 percent. Viewed from the standpoint of 1865 the rate of literacy for blacks increased by 200 percent in fifteen years and by 400 percent in thirty-five years.”[iv]

Emancipation had equally dramatic economic impacts. It amounted to nothing less that the “confiscation of about three billion dollars of property – the equivalent as a proportion of the national wealth to at least three trillion dollars in 1990.”[v]

In effect, the government in 1865 confiscated the principal form of property in one-third of the country, without compensation. That was without parallel in American history – it dwarfed the confiscation of Tory property in the American Revolution. When such a massive confiscation of property takes place as a consequence of violent internal upheaval on the scale of the American Civil War, it is quite properly called revolutionary.[vi]

McPherson sites other economic impacts of emancipation including the redistribution of income in the South post war which “was by far the greatest in American history.”[vii] Equally dramatic was the change in political power in the post war South that resulted from the freeing of the slaves. Blacks achieved the vote in 1868 and within a year represented the majority of registered voters. In four years, 15 percent of the officeholders in the South were black. [viii] “In 1870, blacks provided three-fourths of the votes in the South for the Republican party, which controlled the governments of a dozen states in which five years earlier most of these black voters had been slaves. It was this phenomenon, more than anything else, that caused contemporaries to describe the events of those years as a revolution[ix] This fact caused the pendulum of thought to swing back in the 1980s to support of the Civil War and Reconstruction experiences as revolutionary.

Historian Eric Foner calls the post war period in history “Radical Reconstruction” and found it unequaled in history in its support of the black laborer and th eir political rights. Regrettably, some of the gains made were reversed by the counterrevolution that followed when the Democratic Party was revived in the north and the indifference of the Republicans of the north toward blacks in the south increased. But, as McPherson points out, “the counterrevolution was not as successful as the revolution had been.” Blacks in the south remained free, continued to have the vote, could still own land, and could still go to school.[x]

eir political rights. Regrettably, some of the gains made were reversed by the counterrevolution that followed when the Democratic Party was revived in the north and the indifference of the Republicans of the north toward blacks in the south increased. But, as McPherson points out, “the counterrevolution was not as successful as the revolution had been.” Blacks in the south remained free, continued to have the vote, could still own land, and could still go to school.[x]

_________________

Note: I highly recommend historian Eric Foner’s website for access to a number of his articles and to his lectures on the Columbia American History Online (CAHO) site. You can register for a free trial subscription to CAHO.

Photos: First: Ruins seen from the capitol, Columbia, S.C., 1865. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Ref. # 165-SC-53. Second: Several generations of a family are pictured on Smith’s Plantation, South Carolina, ca. 1862. (Library of Congress)

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

Share it!

[i] James McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press), 11., [ii] Ibid., 14., [iii] Ibid., 16., [iv] Ibid. [v] Ibid., 17. McPherson sites studies by Roger Ransom and Richard Sutch., [vi] Ibid., 17-18., [vii] Ibid., 18., [viii] Ibid., 19., [ix] Ibid., [x] Ibid., 23.

The Civil War as Revolution – Part I

[Note: This post is part of a series on The Civil War as Revolution which is available at the following links: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

————-

Earlier this month, I posted some thoughts on Abraham Lincoln as revolutionary. It ties to one of the topics we were asked to consider this term, whether the Civil War should be considered the second American revolution. I suspect it is an essay question in many American history programs dealing with the Civil War. I’d like to explore this over the next several posts. A proper place to start is with the question, what is revolution?

![Fist [Source Wikopedia Commons]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Fist.png/421px-Fist.png) According to William A. Pelz in his study on the history of German social democracy, “revolution” comes from the German word “Ugmwälzung” which means “rotation,” as in the turning of an axle. He posits that “in the socio-political realm, revolution means the displacement of a state, governmental, social and economic system by another, higher, more developed state, governmental, social and economic system… Two things are essential to the concept of revolution: that the rotation (Ugmwälzung) be comprehensive and fundamental–that everything old and antiquated be thrown out, weeds torn out by their roots; that a higher and better state replace that which has been done away with. Both conditions must be maintained.”[i] Thus social revolution results in nothing less than transformation.

According to William A. Pelz in his study on the history of German social democracy, “revolution” comes from the German word “Ugmwälzung” which means “rotation,” as in the turning of an axle. He posits that “in the socio-political realm, revolution means the displacement of a state, governmental, social and economic system by another, higher, more developed state, governmental, social and economic system… Two things are essential to the concept of revolution: that the rotation (Ugmwälzung) be comprehensive and fundamental–that everything old and antiquated be thrown out, weeds torn out by their roots; that a higher and better state replace that which has been done away with. Both conditions must be maintained.”[i] Thus social revolution results in nothing less than transformation.

- Painting by Eugene De la Croix (Charenton-Saint-Maurice, 1798 – Paris, 1863) July 29, Liberty guiding the people. Musée du Louvre. Public Domain

Pelz offers two examples of undisputable social revolution. The first, not surprisingly, is the French Revolution, “…the revolution par excellence…that swept away the last remains of medieval feudalism and created the foundation of modern bourgeois society.”[ii] The second example – though hardly resembling the first – was none the less more profound. It was triggered by “the introduction of machine work, which fundamentally altered the nature of work and thereby the basis of state and social life. Every sphere of human existence was penetrated by this revolution (Umwälzung). These two organically related revolutions (Umwälzungen) born of the same impetus, only manifesting themselves differently, are probably the most important revolutions known to history. They toppled and purged from top to bottom and brought humanity forward with a violent jolt.”[iii]

Revolution in politics has been described as “fundamental, rapid, and often irreversible change in the established order.”[iv]

- Da Vinci

Revolution involves a radical change in government, usually accomplished through violence[,] that may also result in changes to the economic system, social structure, and cultural values. The ancient Greeks viewed revolution as the undesirable result of societal breakdown; a strong value system, firmly adhered to, was thought to protect against it. During the Middle Ages, much attention was given to finding means of combating revolution and stifling societal change. With the advent of Renaissance humanism, there arose the belief that radical changes of government are sometimes necessary and good, and the idea of revolution took on more positive connotations. John Milton regarded it as a means of achieving freedom, Immanuel Kant believed it was a force for the advancement of mankind, and G.W.F. Hegel held it to be the fulfillment of human destiny. Hegel’s philosophy in turn influenced Karl Marx.[v]

Historian James McPherson offers the following as a “common sense” definition for revolution: “an overthrow of the existing social and political order by internal violence.”[vi] With this as background the question becomes, does the American Civil War qualify for revolution status? Was it sufficiently transforming?

- Mark Twain

More in tomorrow’s post but let me leave you with this quote from Mark Twain.

No people in the world ever did achieve their freedom by goody-goody talk and moral suasion: it being immutable law that all revolutions that will succeed must begin in blood, whatever may answer afterward.

– A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

[Addendum: This series on The Civil War as Revolution continues at the following links: , Part II, , Part III,, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

[i] Pelz, William A. and William A. Pelz, eds. Wilhelm Liebknecht and German Social Democracy: A Documentary History. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994), 264-265, Book on-line. Available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=15096547. Internet. Accessed 13.October 2007.

[ii] Ibid., 265.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Encyclopedia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2007

[v] Ibid.

[vi] James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 16.

In the spring of 1850, another nativist fraternity, The Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB) was founded in New York City by Charles B. Allen, a thirty-four-year-old commercial agent born and educated in Massachusetts. (1) At first a simple “local fellowship numbering no more than three dozen men, there was little to distinguish their order from many other ‘patriotic’ groups, little reason for anyone to expect that it would be the core of a major political party, the greatest achievement of nativism in America.” (1) By 1852, it began to grow quickly and leaders of the Order of United Americans (OUA) took notice. Many of their membership joined and the OSSB membership swelled “from under fifty to a thousand in three months.” (1) Later that year, the two organizations joined under the leadership of James Barker and, with astute organizational skill, hundreds of lodges were formed “all over the country with an estimated membership ranging up to a million or more.” (2) Those who joined promised, as a part of secret rituals, to “vote for no one except native-born Protestants for public office” and “the Order endorsed certain candidates or nominated its own” in secret councils. Because their rules required them to say they “knew nothing” about the organization if asked, the movement became known as the “Know Nothings” (3)

In the spring of 1850, another nativist fraternity, The Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB) was founded in New York City by Charles B. Allen, a thirty-four-year-old commercial agent born and educated in Massachusetts. (1) At first a simple “local fellowship numbering no more than three dozen men, there was little to distinguish their order from many other ‘patriotic’ groups, little reason for anyone to expect that it would be the core of a major political party, the greatest achievement of nativism in America.” (1) By 1852, it began to grow quickly and leaders of the Order of United Americans (OUA) took notice. Many of their membership joined and the OSSB membership swelled “from under fifty to a thousand in three months.” (1) Later that year, the two organizations joined under the leadership of James Barker and, with astute organizational skill, hundreds of lodges were formed “all over the country with an estimated membership ranging up to a million or more.” (2) Those who joined promised, as a part of secret rituals, to “vote for no one except native-born Protestants for public office” and “the Order endorsed certain candidates or nominated its own” in secret councils. Because their rules required them to say they “knew nothing” about the organization if asked, the movement became known as the “Know Nothings” (3)

of schools and colleges taught “Southern Nationalism” and impressed on the minds of students the “standard ‘line’ on the issues of slavery, politics, and economics.”

of schools and colleges taught “Southern Nationalism” and impressed on the minds of students the “standard ‘line’ on the issues of slavery, politics, and economics.”

![Photo of Unfinished portrait miniature of Oliver Cromwell by Samuel Cooper Public Domain [Wikipedia]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/17/Cooper%2C_Oliver_Cromwell.jpg)

![Wikipedia Commons]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a0/Declaration_of_Human_Rights.jpg)

![King George III in Coronation Robes Public Domain [Wikipedia Commons]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b1/George_III_in_Coronation_Robes.jpg)