Posts Tagged ‘Causes of the Civil War’

New in Paperback – This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War

The good folks at Oxford University Press recently sent me a copy of the new paperback edition of James McPherson’s This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War. First published in 2007, it comprises 16 essays in which McPherson attempts to answer the following questions:

- Why did the war come?

- What were the war aims of each side?

- What strategies did they employee to achieve these aims?

- How do we evaluate the leadership of both sides?

- Did the war’s outcome justify the immense sacrifice of lives?

- What impact did the experience of war have on the people who lived through it?

- How did later generations remember and commemorate that experience?

- Author: James M. McPherson

- Publisher: Oxford University Press

- ISBN13: 9780195392425

- ISBN10: 0195392426

- Paperback, 272 pages

- Sep 2009

I read the hardback version in 2007 and can highly RECOMMEND.

FYI – Amazon has the paperback version available for here for $12.21.

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 5 Beecher’s Bibles

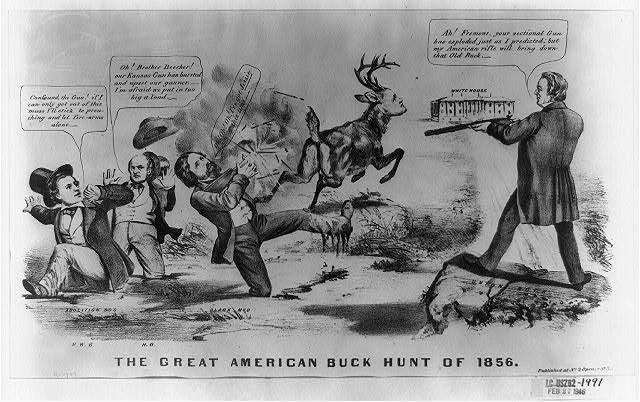

Digital ID: cph 3b37012 Source: b&w film copy neg. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-90663 (b&w film copy neg.) , LC-USZ62-1991 (b&w film copy neg.) Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

The potential for violence after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and indeed episodes of violence, increased on the border between Missouri and Kansas as both Free Soiler and pro-slavery factions began actively arming themselves. An agent of the New England Emigrant Aid Society in Kansas, Charles L. Robinson, requested with some urgency a shipment of several hundred rifles and field guns.(i) Guns were sent to aid Free Soilers in Kansas often with the support of northeastern clergy and their congregations. Thus Sharps Rifles sent by Henry Ward Beecher’s congregation became know as “Beecher Bibles”. Likewise, according to Potter, armed militias from the South began forming to support the pro-slavery cause in Kansas. (i)

Henry Ward Beecher (Source: Library of Congress Brady-Handy Photograph Collection (LC-BH82- 5388 A))

This post continues the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, and Part 4 here.

ABOUT THE POLITICAL CARTOON: Another Currier satire favoring American party candidate Millard Fillmore. A “buck” (James Buchanan) runs toward the White House, visible in the distance, as the two rival candidates take aim at him with their shotguns. Republican John C. Fremont’s gun explodes (left), as he struggles to free himself from a pool of “Black Mud.” On the far left his two abolitionist supporters Henry Ward Beecher and editor Horace Greeley are also mired in an “Abolition Bog.” Fremont: “Oh! Oh! Oh! I’ve got Jessie this time–” (a puzzling allusion to his wife Jessie Benton). Greeley: “Oh! Brother Beecher! our Kansas Gun has bursted and upset our gunner. I’m afraid we put in too big a load.” Reference is to the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 and the ensuing violence in Kansas, an issue exploited by the Republicans. Beecher: “Confound the Gun! if I can only get out of this muss I’ll stick to preaching and let fire-arms alone.” The oblique reference to Beecher’s part in outfitting armed antislavery emigrants for Kansas is made in more obvious terms in “Col. Fremont’s Last Grand Exploring Expedition in 1856” (no. 1856-20). On “Union Rock” (right), which is square in the path toward the White House, stands Millard Fillmore. He aims his flintlock at Buchanan and says confidently, “Ah! Fremont, your sectional Gun has exploded just as I predicted; but my American rifle will bring down that Old Buck.” MEDIUM: print on wove paper : lithograph ; image 24 x 39 cm. CREATED/PUBLISHED: N.Y. : Published at No. 2 Spruce Street, [1856] Source: Library of Congress

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

The Compromise of 1850: Effective Political Action or Forecast of Disaster?

Thanks to everyone that has participated in the Compromise of 1850 Poll going on here. If you haven’t voted, please do!

To expand the discussion, let me share my perspective on the question I raised, whether The Compromise of 1850 was an effective political action or a forecast of disaster.

The United States Senate, A.D. 1850. Drawn by P. F. Rothermel; engraved by R. Whitechurch. c1855. Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Number: LC-USZCN4-149

Michael F. Holt makes an excellent case in his classic, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s , that the Compromise of 1850 was more a forecast of disaster than effective political action. His argument is founded on the premise that the Compromise was effectively a deathblow to the Second American Party System and the notion that the health of America’s political parties in the mid-19th century was crucial to containment of sectional strife. As long as “men had placed their loyalty to their own party and defeat of the opposing party within their own section ahead of sectional loyalty, neither the North nor the South could be united into a phalanx against the other.” (1)

This conclusion is, of course, more easily arrived at when looking back at the period through the lens of generations with the full knowledge that the country would be ripped apart within fifteen years in a tumultuous Civil War. The perspectives of the politicians who negotiated the Compromise of 1850 would have, at the time, been much different. Indeed, they might have seen it as artful politics. The agreements made in the Compromise appeared to solve, at least temporarily, the country’s major ills which – on the surface – revolved around slavery and the country’s expansion.

But the effect was the displacement of the country’s trust in “party” as voice and defender of political views. The void caused men to affiliate more with their section, North and South. The scene was set for the country’s festering issues to rise again to a boil, this time without the benefit of cross-sectional parties that had so successfully contained discord in the past.

Thus my conclusion is that the Compromise of 1850 was BOTH an effective political action AND a forecast of disaster. It was effective for a time in that it allowed the country to continue forward with at least a fragile agreement on monumental issues. But its destruction of the Second American Party System led the country toward potential destruction.

And so…. what do you think? Comments welcome.

—-

See images of the original document – The Compromise of 1850 here.

(1) Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s, (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1983), 139.

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 8

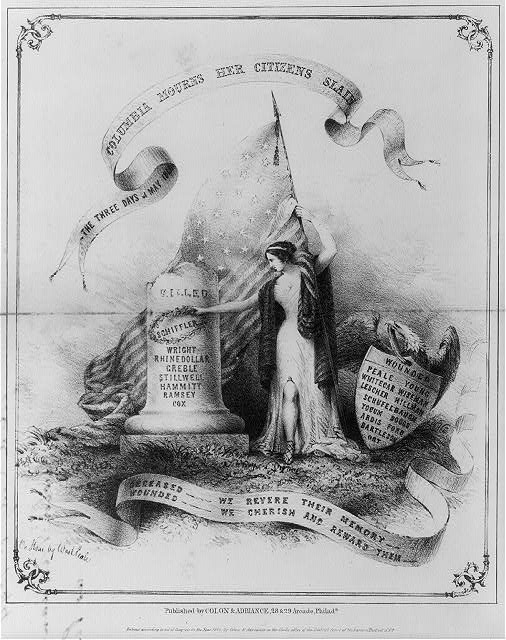

The three days of May 1844. Columbia mourns her citizens slain. Source: Library of Congress

Few would argue that a resurgence of nativism in the mid-19th century had a rational footing. It was, rather, “a nonrational response to contemporary problems” in “an age of social upheaval, an age of deprivation, stress, and imminent disaster.”

The nation was not facing civil war because of immigration from Ireland and Germany. The dislocations of urban-industrial growth were not produced by the newcomers, more victims than villains in this story. Attacking the Irish would not resolve the dilemma of sectional strife. Striking out at the aliens would not bring an end to socioeconomic changes or even the illusion of stability.

But embracing an antialien movement would allow frustrated nativists a sense of “escape from the central problems of their time. Unwilling to accept the dark side of their American experience—the wages of slavery, the stresses of a competitive culture, the crisis of community—they struck out at the most vulnerable group within their midst.” Thus Bennett posits, “the Know Nothing movement and the great appeal of nativism are found in concerns about immigration and historic fears of Catholicism.”

Many nativists thought the solution to the growing turmoil was to return to that which was familiar in the nation’s past, waging battle against an invading alien threat.

Americanists constructed a polarized world in which the enemy (now Catholic Irish and Germans) was an alien intruder and they were the “chosen people.”

In the end, Bennett asserts, the membership of the American Party would discover that “the issues over which they differed were as important as the religious, ethnic, and political bonds that united them.” Even though they achieved considerable early success as a party, they had not found a way to handle the great divisive issue of the day, slavery.

David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement , (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 94, 103, 119.

About the image.

A memorial to nativist casualties of the violent clashes occurring between anti-foreigner “Native Americans” and Irish-American Catholics in Kensington, Philadelphia, May 6 through 8, 1844. The female figure of Columbia holds a large, billowing American flag near a broken column on which she places a wreath. On the column are the names of those Native Americans killed during the attacks on Catholic homes and institutions. At the top of the list, circled by Columbia’s wreath, is the name of George Schiffler, the first and most famous of the nativist martyrs. Other names inscribed on the column are: Wright, Rhinedollar, Greble, Stillwell, Hammitt, Ramsey, and Cox. To the right of Columbia is an American eagle supporting a shield with the names of the wounded, including: Peale (the artist?), Whitecar, Lescher, Young, Wiseman, Willman, Schufelbaugh, Yocum, Ardis, Boggs, Ford, Bartleson, and Ort. Above the figure floats a streamer with the print’s title. Below a similar banner reads “Deceased—-We Revere Their Memory—Wounded—We Cherish And Reward Them—.”

Medium: lithograph on wove paper

Published by Colon & Adriance, 28 & 29 Arcade, 1844.

Library of Congress Call Number: LOT 10615-34 [item] [P&P]

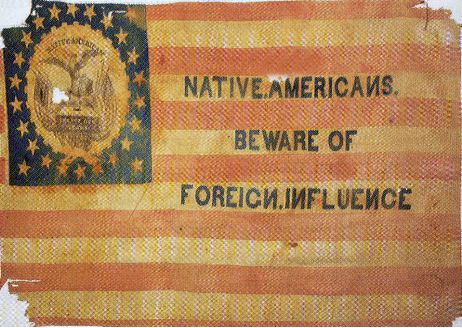

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 5

Flag of the Know Nothing Party

Historian James McPherson points out that the membership in the Know Nothings was “drawn primarily from young men in white-collar and skilled blue-collar occupations. A good many of them were new voters. One analysis showed that men in their twenties were twice as likely to vote Know Nothing as men over thirty.” (1)

Their leaders were also “new men” in politics who reflected the social backgrounds of their constituency. In Pittsburg, more than half of the Know-Nothing leaders were under thirty-five and nearly half were artisans and clerks. Know Nothings elected to the Massachusetts legislature in 1854 consisted mainly of skilled workers, rural clergymen, and clerks in various enterprises. Maryland’s leaders were younger and less affluent than their Democratic counterparts.” (1)

For more information on the Know Nothing Party in Massachusetts, see the Massachusetts Historical Society here.

(1) Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States), (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 135-136.

Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States), (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 135-136.

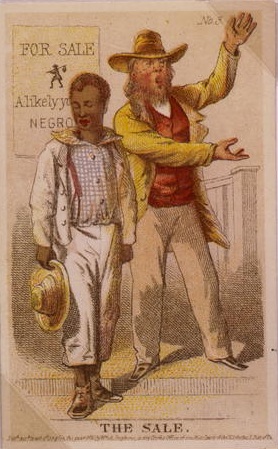

On Slavery – 7 Slavemongering

Green Hill Plantation, Slave Auction Block, State Route 728, Long Island vicinity, Campbell County, VA Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Many words lose their relevance and thus usage over time. Fortunately, slavemongering, is among them.

A monger is defined as a dealer or trader. To monger is to promote or deal in something specified. It is generally used in a composition. Thus a costermonger is an itinerant fruit-seller, a fellmonger is a dealer in skins, a fishmonger peddles fish, and an ironmonger is a dealer in iron goods.

Walter William Skeat’s An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, suggests as possible source of the word.

monger, mangere a dealer merchant formed with suffix ere from mang ian – to traffic barter gain by trading.

The relationship to the Lat[in] mango, a dealer in slaves, is not clear but the [English] word does not appear to have been borrowed from it. [1]

Slaves were “inseparable from any species of private property” and since “titles to slaves were transferable,” their owners had the power of conveyance. [2] Thus the legality of slavemongering, or the trafficking of slaves, was firmly established in the Antebellum South.

Slave owners seemed somewhat ambivalent to the idea of slavemongering. Some despised the idea but took advantage of it non-the-less. Thus one who found the sale of a bondsman distasteful or even bordering on amoral, could unburden themselves of their human property using a professional.

Franklin & Armfield had the distinction of being the the largest slave-trading enterprise in the South at least during the period prior to the Panic of 1837. Formed in 1828, its principles were John Armfield and Isaac Franklin. They each “accumulated fortunes in excess of a half million dollars” before retiring. [2]

Hundreds of small entrepreneurs engaged in slave trade but only a few made large sums of money. Among these few was Nathan Bedford Forrest who “was the largest slave trader in Memphis during the late 1850’s; he was reputed to have made a profit of $96,000 in a single year.” [2]

[1] Walter William Skeat, An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, accessed on the internet via Google Books, November 22, 2008 here.

[2] Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South.

On Slavery – 5 Escaping

Historian Kenneth Stampp makes an interesting point about differing locations of slaves determining the destination of escapees. Those living near Indians might, for example, seek refuge with local tribes, as was the case in Florida.

“…Florida slaves escaped to the Seminole Indians, aided them in their wars against the whites, and accompanied them when they moved to the West. At Key West, in 1858, a dozen slaves stole a small boat and successfully navigated it to freedom in the Bahamas. Arkansas runaways often tried to make their way to the Indian country.” (Stampp, 120)

Those nearer to the north often choose to escape to the north where there was a greater presence of abolitionists.

Those in Texas would escape in larger numbers to Mexico.

“In Mexico the fugitives generally were welcomed and protected and in some cases sympathetic peons guided them in their flight.” (Stampp, 120)

Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South

On Slavery – 4

Cotton Harvest, U.S. South,1850s Reference BLAKE4, as shown on http://www.slaveryimages.org, sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library.

The experience of slaves could vary by region due in large part to the type of product the slave was engaged in bringing to market. Slaves in the hemp producing regions of Kentucky and Missouri, worked in rhythm with the cycles required by the crop. Similarly, slaves who worked in cotton producing areas (above) or regions in which tobacco was cultivated, would have had daily and seasonal work routines aligned with those crops. Regional weather would also have differentiated the experience of slaves in different parts of the south.

Slaves rented out to work in industrial areas with factories would have had a decidedly different experience than those working on a plantation. Author Kenneth Stampp suggests that factory slaves enjoyed more freedom and yet an equal if not higher incidence of overwork. The daily experience of slaves living in urban centers would have been decidedly different than rural slaves. Domestic assignments were not uncommon.

On Slavery – 3

[This post continues the series On Slavery (1 here and 2 here).]

"Flogging the Negro" (Cropped) Full Image Reference NW0213, as shown on http://www.slaveryimages.org, sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library.

Kenneth Stampp in his book, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South, suggests that some owners of slaves were conflicted about the need to apply punishment in the control of slaves and yet most felt fully justified in imposing that control. He sites on numerous occasions the willingness of owners to overlook the cruelty of overseers if they met or exceeded production goals. This head-in-the-sand approach to ethics undoubtedly had many causes but the most obvious was greed.

Owners also considered their slaves to have a “duty” to their master by virtue of the fact that they were, after all, his property and that the master provided and cared for them. But the most prevalent justification for imposing control on the slaves was to achieve maximum production from them as a labor force. Poor performers, for whatever reason, were seen as impacting the bottom-line.

On Slavery – 1

Photograph of Slave Cabin and Occupants Near Eufala, Barbour County, Alabama (Photo source: Library of Congress)

I’m reading Kenneth M. Stampp’s fascinating book, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South for class. A focus this week and next is, among other things, the ways in which slave owners controlled their bondsmen. The methods varied considerably as did the ethical sensibilities of the masters and overseers. Stampp suggests that behavioral control included both the carrot and the stick with heavy weighting on the stick. That is to say, some masters and/or overseers used positive incentives and some negative.

Positive incentives included: work stoppage at noon on Saturdays and Sunday off, holidays off, parties and dances, holiday gifts, cash for the best worker for a given period, the right to grow one’s own crops whether for personal food or sale, the right to rent oneself out and keep some of the income, and the ultimate incentive, the right to achieve freedom.

Negative incentives were many. Stampp suggests that few adult slaves did not have some experience with flogging. This seemed to be the most acceptable method of disciplining slaves and was used extensively. Other forms of physical punishment used to control slaves included: confinement either in “the blocks” or even jail, mutilation (ranging from castration to branding), and even more severe forms of torture. For young slaves or those who needed “breaking,” there were actually specialists who through, undoubtedly mental and physical persuasion, reduced high spirited individuals to more pliable and subservient workers.

Another method of control was the introduction of religion to the slaves. Indoctrination of slaves into Christianity had its advantages. It was not uncommon for them to ensure that sermons emphasized those verses in the Bible that instructed servants to obey their masters. (Stampp, 158) Particular focus was made on teaching slave children “respect and obedience to their superiors” in the belief that it made them better servants. (Stampp, 159) This suggests a fascinating area of study – the effects of religion on American slaves – for which I must look for information. Let me know if you can recommend any.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part VIII: The Influence of the Individual

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes, Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity, and Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control.

___________________

Civil War scholar Gabor Boritt posits a fascinating theory that the impact of an individual can, in fact, be more influential in the determination of history’s direction than the long confluence of time.[i] “…It may be declared with confidence that a giant in the earth, or a crucial moment, weighs more in the scales of history than dreary ages.”[ii] The giant of which he spoke was Abraham Lincoln. His view makes Lincoln a central figure of both American mythology and history. Lincoln’s role in the coming of the Civil War he “divides into four increasingly important stages.”[iii]

Civil War scholar Gabor Boritt posits a fascinating theory that the impact of an individual can, in fact, be more influential in the determination of history’s direction than the long confluence of time.[i] “…It may be declared with confidence that a giant in the earth, or a crucial moment, weighs more in the scales of history than dreary ages.”[ii] The giant of which he spoke was Abraham Lincoln. His view makes Lincoln a central figure of both American mythology and history. Lincoln’s role in the coming of the Civil War he “divides into four increasingly important stages.”[iii]

- First, in the 1850s as tensions grew, Lincoln was one of many political leaders,

familiar mostly in and around Illinois, though as the decade progressed so did his reputation in the North.

- Second, in 1860 he won the presidential nomination of the Republican [P]arty and became a nationally known figure.

- Third, from his election in early November to his inauguration on March 4, 1861, he was the president-elect.

- Fourth, in the White House he presided over events that led to Sumter.

As one stage followed another, Lincoln’s stand changed only gradually, but his voice grew ever more weighty until the end when, together with the voice of President Jefferson Davis, it proved to be decisive.[iv]

I would suggest that there were others whose individual influence – while perhaps not equal to that of Lincoln’s – none the less, impacted the direction of the nation. Key to the South was the “triumvirate of secession” – extremists Robert Rhett, William Yancey, and Edmun Ruffin (pictured below). Each, according to his gifts, kept the pressure for secession constant, the evils of the North apparent. In the period after Lincoln’s election, they leveraged the fear, uncertainty and doubt created by Northern and Southern newspapers to move the populous from defeat to secession as the only alternative left.[v] [See more about Rhett, Yancey and Ruffin in my post “The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War” here.]

They fought delay. Many of the leaders had long believed the Union a curse to the South and they feared that if they moved too deliberately the North might offer favorable terms. Others urged quick action lest the people cool off and accept less than justice. They must strike while the iron was hot. Delay was their worst enemy.

By December 17, 1860, Rhett and his followers had secured a convention in South Carolina, composed of those who were ready to stand alone, if necessary, in defense of Southern rights. The next day an ordinance of secession was adopted. Within six weeks, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had followed South Caroline’s example. The Cotton Kingdom was ready to form itself into the Confederate States of America.[vi]

Is it a wonder that Edmun Ruffin was among the first to fire a cannon on Fort Sumter?

At a nearby battery, another fire-eater was ready. Edmund Ruffin, with his long flowing white hair, another momentary exile from a still reluctant Virginia, sixty seven-year-old honorary Palmetto Guard, was ready. Staring into the dark, knowing where the enemy was, he sent the first shot from a columbaid into the fort flying the unseen flag of the United States.[vii]

Key individuals in the North included those who catapulted the Abolitionist message into the public consciousness. For this reason, John Brown must be included. The men surrounding Lincoln – Seward, Chase, Bates, Douglas and Buchanan – also deserve a chair.

And So What the Cause?

The Civil War can be attributed to no single cause. Slavery was undeniably an influencing factor – a common thread – inexorably tied to the sectional crises that evolved as the country expanded. Profound sectional differences – social, cultural, spiritual, economic, political – provided sufficient tender to ignite into violent conflict – given the spark. The “fanatical edge” and our politicians created the sparks that erupted in violence and pushed the nation over the precipice and into war. Several key individuals tipped the balance. Chief among these were: the Southern fire-eaters Rhett, Yancey and Ruffin, abolitionists who turned up the heat of anti-slavery sentiments in the North, and – pointedly – Abraham Lincoln himself.

For more reading, I highly recommend Gabor S. Boritt’s Why the Civil War Came. His essay titled “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility” is excellent. Avery Craven’s The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. provides very interesting commentary on Rhett, Yancey, and Ruffin (and more about their individual strengths) and a wealth of information on Antebellum America and its march toward war.

In the next post, I’ll tackle the second question of the series: The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

_______________________

[i] “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 7., [ii] Ibid., [iii] Ibid., [iv] Ibid.

[v] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 19 57), 433., [vi] Ibid.

57), 433., [vi] Ibid.

[vii] Boritt, “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 5.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes and Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity.

___________________

Political discord represents yet another candidate for the war’s cause. Late historian William E. Gienapp (pictured right) suggests that “however much social and economic developments fueled the sectional conflict, the coming of the Civil War must be explained ultimately in political terms, for the outbreak of war in April 1861 represented the complete breakdown of the American political system. As such, the Civil War constituted the greatest single failure of American democracy.”[i]

Political discord represents yet another candidate for the war’s cause. Late historian William E. Gienapp (pictured right) suggests that “however much social and economic developments fueled the sectional conflict, the coming of the Civil War must be explained ultimately in political terms, for the outbreak of war in April 1861 represented the complete breakdown of the American political system. As such, the Civil War constituted the greatest single failure of American democracy.”[i]

Gienapp poin ts to the role of slavery as the underlying cause of the sectional conflict. “Without slavery it is impossible to imagine a war between the North and the South (or indeed, the existence of anything we would call “the South” except as a geographic region).”[ii] He also asserts that America’s slave heritage was completely associated with race. That is, had the slaves brought to America been white, the practice would have disappeared much earlier.[iii] But an argument asserting slavery as chief cause of the war neglects the fact that not only was it older than the republic, but “for over half a century following adoption of the Constitution, the institution had only sporadically been an issue in national politics, and it had never dominated state politics in either section.”[iv] What changed? It was the rise of the slavery issue in American society; that is, the heightened awareness of it. This development was rooted in a number of changes in American society in the first half of the nineteenth century already addressed.[v]

ts to the role of slavery as the underlying cause of the sectional conflict. “Without slavery it is impossible to imagine a war between the North and the South (or indeed, the existence of anything we would call “the South” except as a geographic region).”[ii] He also asserts that America’s slave heritage was completely associated with race. That is, had the slaves brought to America been white, the practice would have disappeared much earlier.[iii] But an argument asserting slavery as chief cause of the war neglects the fact that not only was it older than the republic, but “for over half a century following adoption of the Constitution, the institution had only sporadically been an issue in national politics, and it had never dominated state politics in either section.”[iv] What changed? It was the rise of the slavery issue in American society; that is, the heightened awareness of it. This development was rooted in a number of changes in American society in the first half of the nineteenth century already addressed.[v]

As mentioned in previous posts in this series, the abolitionist movement did a great deal to raise that awareness. But Gienapp suggests that “it was the politicians themselves, as part of the struggle for control of the two major parties, wh o ultimately injected the slavery issue into national politics.”[vi] The key development was the introduction in Congress in 1846 of the Wilmot Proviso, which prohibited slavery from any territory acquired from Mexico, by a group of Van Burenite Democrats who were angry with President James K. Polk (pictured right) and his southern advisers. Once the slavery issue, in the shape of the question of its expansion into the western territories, entered the political arena, it proved impossible to get it out. The issue took on a life of its own, and when politicians tried to drop the issue after 1850, they discovered that many voters were unwilling to acquiesce.[vii]

o ultimately injected the slavery issue into national politics.”[vi] The key development was the introduction in Congress in 1846 of the Wilmot Proviso, which prohibited slavery from any territory acquired from Mexico, by a group of Van Burenite Democrats who were angry with President James K. Polk (pictured right) and his southern advisers. Once the slavery issue, in the shape of the question of its expansion into the western territories, entered the political arena, it proved impossible to get it out. The issue took on a life of its own, and when politicians tried to drop the issue after 1850, they discovered that many voters were unwilling to acquiesce.[vii]

Gienapp makes a good case for the war’s true cause in the following discourse.

A second critical development, intimately related to the first, was the crystallization of rival sectional ideologies oriented toward protecting white equality and opportunity. Increasingly, each section came to see the other section and its institutions as a threat to its vital social, political, and economic interests. Increasingly, each came to think that one section or the other had to be dominant. Informed by these ideologies, a majority of the residents of each section feared the other, and well before the fighting started the sectional conflict represented a struggle for control of the nation’s future.

It fell to the political system to adjudicate differences between the sections and preserve a feeling of mutual cooperation and unity. And for a long time the political system had successfully defused sectional tensions. Because it brought northern and southern leaders together, Congress was the primary arena for hammering out solutions to sectional problems. In various sectional confrontations–the struggle over the admissi

on of Missouri as a slave state in 1819-21, the controversy over nullification and the tariff in 1833, the problem of the status of slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico in 1850, and the struggle over the proslavery Lecompton constitution in 1858-Congress had always managed to find some acceptable way out of the crisis.

Yet the American political system was particularly vulnerable to sectional strains and tensions. One reason was the institutional structure of American politics. The Civil War occurred within a particular political institutional framework that, while it did not make the war inevitable, was essential to the coming of the war.

Integral to this institutional framework was the United States Constitution. While some aspects of the Constitution retarded the development of sectionalism, it contained a number of provisions that strengthened the forces of sectional division in the nation. No constitution can anticipate all future developments and conclusively deal with all controversies that subsequently arise. The purpose in analyzing the Constitution’s role in the sectional conflict is not to fault its drafters or condemn it as a flawed document, but rather to indicate the importance of certain of its clauses for the origins of the war.

One signifi

cant feature of the Constitution was its provision for amendment. Lurking beneath the surface in the slavery controversy was white Southerners’ fear that the Constitution would be amended to interfere with the institution. In advocating secession after Abraham Lincoln’s election, Governor Andrew B. Moore of Alabama (pictured above) predicted that the Republicans would quickly create a number of new free states in the West, which “in hot haste will be admitted to the Union, until they have a majority to alter the Constitution. Then slavery will be abolished by law in the States.”[viii]

The fear, uncertainty and doubt associated with this possibility, on the part of the Southern political establishment, pushed the country toward war.

The next post: “The Influence of the Individual.”

For further reading, I recommend The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War by Michael F. Holt and Why the Civil War Came, edited by Gabor S. Boritt.

© 2007 Rene Tyree

_________________________

Photo credits:

Historian William E. Gienapp. Source: Harvard Gazette Archives, Issue: April 07, 2005.

Poster Announcing Sale and Rental of Slaves, Saint Helena (South Atlantic), 1829. Source: The Atlantic Slave Trade and

Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record., Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr., The Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Image H003.

President James K. Polk

Cropped image of the constitution of Kansas

Governor Andrew B. Moore of Alabama. Source: Alabama Department of Archive and History

[i] William E. Gienapp, “The Crisis of American Democracy, the Political System and the Coming of the Civil War,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt [book on-line] (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, accessed 1 September 2007), 82; available from questia.com http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=78779127; Internet., [ii] Ibid., [iii] Ibid., [iv] Ibid., [v] Ibid., [vi] Ibid., 83., [vii] Ibid., [viii] Ibid., 86.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, and Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes.

___________________

Historian Gabor S. Boritt asserts that the American Constitution’s “fundamental ambiguity” on a number of matters involving slavery contributed to the sectional controversy that stimulated the growing conflict between the North and the South.[i] The document was vague on the status of slavery in the territories, the power of Congress over the institution in the District of Columbia, whether the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce extended to the slave trade, whether it was a state or federal responsibility to return runaway slaves, and whether Congress could impose conditions on a new state or refuse to admit a new slave state to the Union.[ii] But the most important of these was whether a state had the right to secede from the Union.

Historian Gabor S. Boritt asserts that the American Constitution’s “fundamental ambiguity” on a number of matters involving slavery contributed to the sectional controversy that stimulated the growing conflict between the North and the South.[i] The document was vague on the status of slavery in the territories, the power of Congress over the institution in the District of Columbia, whether the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce extended to the slave trade, whether it was a state or federal responsibility to return runaway slaves, and whether Congress could impose conditions on a new state or refuse to admit a new slave state to the Union.[ii] But the most important of these was whether a state had the right to secede from the Union.

Whereas the Articles of Confederation had proclaimed the Union to be perpetual, the Constitution contained no such statement. Indeed, nowhere did it discuss whether a state could secede or not. In the absence of any explicit provision, neither the nationalists nor the secessionists could present a conclusive argument on the subject. In upholding the perpetuity of the Union, Abraham Lincoln conceded that the language of the Constitution was not decisive.[iii]

This didn’t stop either side from finding in these documents justification of their positions.

Topic of the next post: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

[i] Gabor S. Boritt, “‘And the War Came’? Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility,” in Why the Civil War Came, ed. Gabor S. Boritt [book on- line] (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, accessed 1 September 2007), 85; available from questia.com http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=78779127; Internet.

line] (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, accessed 1 September 2007), 85; available from questia.com http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=78779127; Internet.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.