Jomini on the Nature of War – Part II – The Burgeoning Military Theorist

This post continues from Part I here. Please note links in blue lead to additional information on those topics.

Antoine-Henri Jomini (below right) was born on March 6, 1779 in the small town of Payerne (Payerne church pictured right) in western Switzerland. His family was an old and influential one; his father Benjamin active in local politics. Jomini grew up with the French Revolution and the sight of French soldiers was something he was familiar with even as a boy. He was a teenager working in banking in Paris when the Swiss Revolution of 1798 broke out, largely instigated by the French at the proding of exiled Swiss radicals. Jomini’s father joined the revolutionary cause and served in various political roles in the Helvetian Republic. Antoine-Henri caught the fever of revolution as well and returned home where, at the age of nineteen, he became the secretary to the Swiss minister of war. He attained military rank (captain) and a reputation for being bright, diligent, and full of ambition. By

Antoine-Henri Jomini (below right) was born on March 6, 1779 in the small town of Payerne (Payerne church pictured right) in western Switzerland. His family was an old and influential one; his father Benjamin active in local politics. Jomini grew up with the French Revolution and the sight of French soldiers was something he was familiar with even as a boy. He was a teenager working in banking in Paris when the Swiss Revolution of 1798 broke out, largely instigated by the French at the proding of exiled Swiss radicals. Jomini’s father joined the revolutionary cause and served in various political roles in the Helvetian Republic. Antoine-Henri caught the fever of revolution as well and returned home where, at the age of nineteen, he became the secretary to the Swiss minister of war. He attained military rank (captain) and a reputation for being bright, diligent, and full of ambition. By twenty-one, he had command of a battalion. [i]

twenty-one, he had command of a battalion. [i]

It was during this time that he began a vigorous study of military history. John Shy suggests that Jomini was…

“obsessed by visions of military glory, with himself imitating the incredible rise of Bonaparte (below right) who was only ten years his senior, but in a telling phrase Jomini remembers being possessed, even then, by “le sentiment des principes” — the Platonic faith that reality lies beneath the superficial chaos

of the historical moment in enduring and invariable principles, like those of gravitation and probability. To grasp those principle, as well as to satisfy the more primitive emotional needs of ambition and youthful impatience, was what impelled him to the study of war. Voracious reading of military history and theorizing from it would reveal the secret of French victory.” [ii]

The Luneville Treaty of 1801 (see exerpts here) ended the Napoleonic Wars and Jomini returned to Paris where he maintained a devotion to the study and writing of military theory. He had been enthralled by Napoleon’s leadership. It is beyond disptue that the French had achieved a breakthrough in warfare and Jomini was about trying to find out how they had done it.

“Answering this question, persuasively and influentially, would be Jomini’s great achievement. The wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon generated a vast, receptive audience for the

kind of clear, simple, reassuring explanation that he would offer. Drawing overtly on the prestige of ‘science’ and yet almost religious in its insistent evangelical appeal to timeless verities, Jomini’s answer to this troubling question seemed to dispel the confusion and allay much of the fear created by French military victories.” [iii]

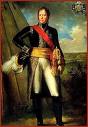

By 1804, Jomini had completed his Traité des grandes opérations militaires (Treastise on Great Milita ry Operations). He managed to ingratiate himself to General Michel Ney (right), leader of Bonaparte’s Sixth Corps, who had served for a time as French viceroy in Switzerland. Ney helped him to publish this first book. It would find its way to Napoleon and Jomini’s life would be forever changed. [iv]

ry Operations). He managed to ingratiate himself to General Michel Ney (right), leader of Bonaparte’s Sixth Corps, who had served for a time as French viceroy in Switzerland. Ney helped him to publish this first book. It would find its way to Napoleon and Jomini’s life would be forever changed. [iv]

Jomini’s principles would also find their way to West Point in the years preceeding the American Civil War. In Part III, I’ll discuss what those principles were.

[i] Hugh Chisholm, The Encyclopedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. 11th Ed, Volume XV. (Cambridge, England: At the University Press, 1911), 495. Accessed online 2/23/2008: here.

[ii, iii, iv] John Shy, “Jomini,” in Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 144 – 149.

Photos: Public Domain – Wiki Commons

Leave a comment