Archive for the ‘Causes of the Civil War’ Category

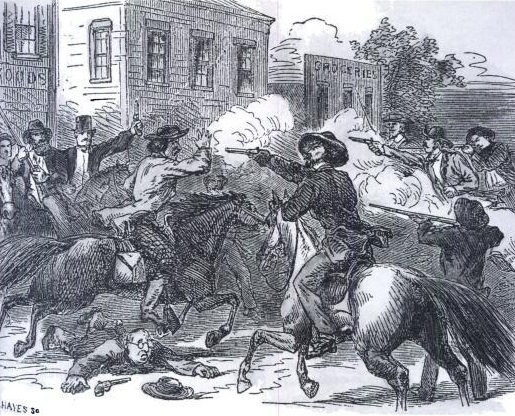

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 7 The Deed

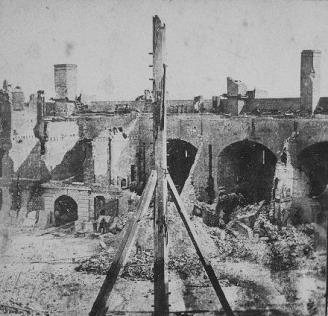

Sacking of Lawrence, 1856

This post completes the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, and Part 5 here, Part 6 here.

Free-State men wounded Douglas County sheriff Samuel J. Jones when he returned to Lawrence to serve arrest warrants in the spring of 1856, despite the presence of Federal troops. The Grand Jury of Douglas County met and “returned indictments against three free-state leaders, against two newspapers at Lawrence – the Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State – and against the Free State Hotel at Lawrence, which, it said, was in fact a fortress, “regularly parapeted and portholed for use of small cannon and arms.” (Potter, 208) There is good evidence that the hotel was, in fact, designed with a mind toward defense with filled portholes that could be knocked out with a rifle butt. But it is curious that indictments of treason were levied toward an inanimate building.

To serve the indictments and associated arrests, United States Marshal Israel B. Donaldson raised a posse inclusive of Missourians. But he left them outside of town as he arrested, along with a deputy, several minor players, others having fled. (Potter, 208) He then attempted to disband the posse but Sheriff Samuel J.Jones, healed of his wounds, rallied the men and rode into Lawrence as a mob force “alleging the need of aid in making arrests and abating nuisances under authority of the grand jury.” (Malin)

To serve the indictments and associated arrests, United States Marshal Israel B. Donaldson raised a posse inclusive of Missourians. But he left them outside of town as he arrested, along with a deputy, several minor players, others having fled. (Potter, 208) He then attempted to disband the posse but Sheriff Samuel J.Jones, healed of his wounds, rallied the men and rode into Lawrence as a mob force “alleging the need of aid in making arrests and abating nuisances under authority of the grand jury.” (Malin)

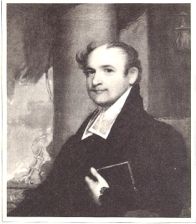

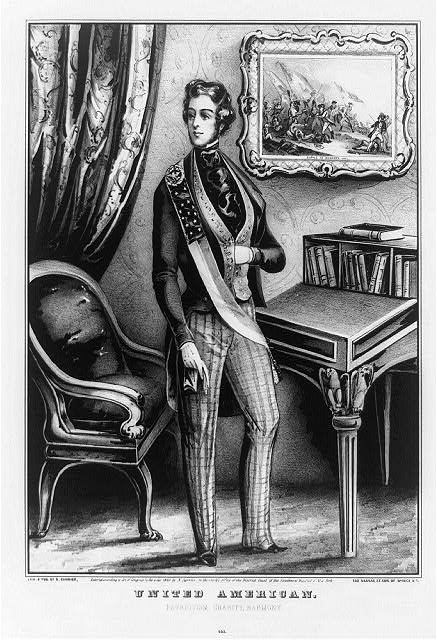

Samuel J. Jones

Michael Holt describes the events of May 21, 1856 as the work of a posse sent by the Lecompton government “to arrest several free state leaders in Lawrence.” (Holt, 194) That posse, “which included Missourians, burned some buildings and destroyed two printing presses but killed no one in the town.” (Holt, 194.) Put in that way, it sounds relatively benign but was pounced on by the Republicans as evidence that the Pierce-backed Kansas territorial government was supporting and condoning atrocities.

“The War Actually Begun,” “Triumph of the Border Ruffians,” “Lawrence in Ruins – Several Persons Slaughtered,” “Freedom Bloodily Subdued,” hyperbolized the Eastern Republican press.” (Holt, 194.) “Kansas was bleeding because lawless slaveholders were butchering defenseless northern settlers in their effort to force slavery on the territory.” (Holt, 194.)

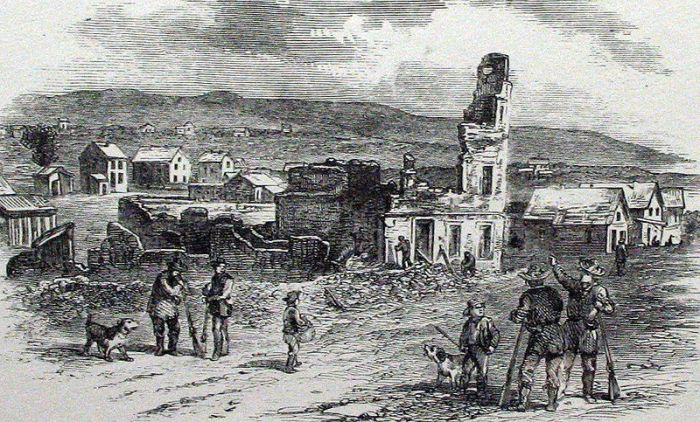

The raid targeted the Free-State Hotel, a building constructed and owned by the New England Emigrant Aid Company. Griffin confirms that Douglas County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones led the posse. He and his men “bombarded the [Free-State] hotel with cannon and then gutted the building with gunpowder and flame. The razing of the hotel, together with the burning of Charles Robinson’s house, the wrecking of the equipment of two newspapers, the Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State, and a certain amount of looting and vandalism, became known as the ‘sack of Lawrence.’” (Griffin)

"Old Sacramento Cannon" captured by U.S. during the Mexican-American War in 1847 and taken to the Liberty Arsenal. The cannon was seized by pro-slavery forces in 1856 and fired during the Sacking of Lawrence. The cannon was damaged in 1896 when it was loaded with clay and straw and fired. Source: Wikipedia Commons

Griffin further claims that proslavery men in the territory justified the action by claiming Jones and his men “were simply executing an indictment of the grand jury of the United States district court at Lecompton and the orders of the presiding judge, Samuel D. Lecompte.” (Griffin)

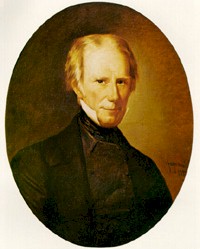

Samuel D. Lecompte

“Free-State men were quick to agree with their enemies, but contended that judge, jury, and Jones had acted illegally and without cause. Newspaper editors sympathetic to the Free-State cause gave the affair enormous publicity — much of it merely falsehoods — and labored to convince their readers that the sack of Lawrence was yet another manifestation of Proslavery barbarism. Before a month was out, Kansas mythology was immensely richer.” (Griffin)

As a final note, both Malin, Griffin, and Holt contend that no one was killed in the raid on Lawrence. But Potter points out that one man, a slave, was killed from falling debris as the Free State Hotel was demolished. (Potter, 209) Clearly it was violent event amidst growing episodes of violence between Free-State and proslavery factions along the border between Kansas and Missouri.

Ruins of the Free State Hotel, after the Sacking of Lawrence, Kansas, 1856

——

C. S. Griffin, “Kansas Historical QuarterlyThe University of Kansas and the Sack of Lawrence: A Problem of Intellectual Honesty,” Kansas Historical Quarterly, Winter, 1968 (Vol. XXXIV. No. 4), pages 409 to 426. Accessed online, February 14, 2009.

Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s, (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1983).

James C. Malin, “Judge Lecompte and the ‘Sack of Lawrence,’ May 21, 1856, ” Kansas Historical Quarterly, August 1953 (Vol. 20, No. 7), pages 465 to 494. Accessed online, February 14, 2009.

David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976).

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 6 The Wakarusa War

Samuel J. Jones

David Potter suggests that much of the discord between Kansans and Missourians was less about slavery and more about land claims.(i) The territory had not yet completed land surveys even six months after it opened for settlement so people squatted on land they wanted. Disputes over those claims, largely between Missourian and new Kansan settlers, sparked the events that culminated in the 1856 raid on Lawrence.

Samuel N. Woods

It began with a killing. A pro-slavery man named Franklin N. Coleman killed in 1855 a Free-Soiler named Charles W. Dow south of Lawrence, Kansas in a land-claim dispute. [An account of the killing by Isaac T. Goodnow can be read here.] Because Coleman claimed self-defense, he was not arrested. In retaliation, a group of Free-Soil men threatened Coleman and his corroborators and burned their property. (ii) Douglas County sheriff Samuel J. Jones was sent to arrest the aggressors but was prevented from doing so by armed Free-Soil men lead by Samuel N. Wood.

Wilson Shannon

Jones accepted the aid of an army of Missouri “Border Ruffians” who converged outside of Lawrence near the Wakarusa River with the intent of enforcing “Law and order in Kansas.” (iii) Then Kansas Territory governor Wilson Shannon averted violence through negotiation (President Pierce refused him Federal troops) and the band dispersed, albeit reluctantly. Because the threat of violence was so great, the episode became known as the Wakarusa War.

Wakarusa River near Lawrence, Kansas - Source: KansasExploring > Larry Hornbaker > Events > Blanton's Crossing

This post continues the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, and Part 5 here.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(ii) Ibid., 207.

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 5 Beecher’s Bibles

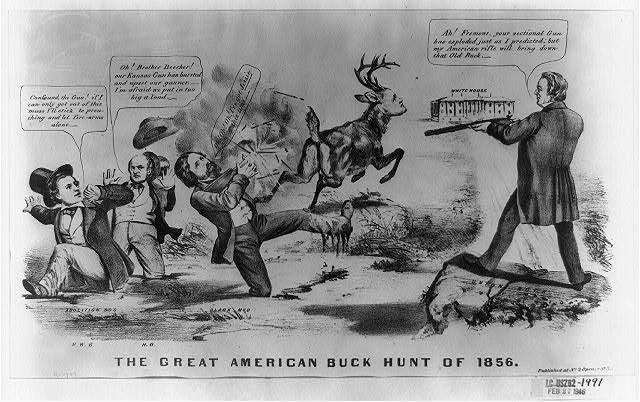

Digital ID: cph 3b37012 Source: b&w film copy neg. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-90663 (b&w film copy neg.) , LC-USZ62-1991 (b&w film copy neg.) Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

The potential for violence after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and indeed episodes of violence, increased on the border between Missouri and Kansas as both Free Soiler and pro-slavery factions began actively arming themselves. An agent of the New England Emigrant Aid Society in Kansas, Charles L. Robinson, requested with some urgency a shipment of several hundred rifles and field guns.(i) Guns were sent to aid Free Soilers in Kansas often with the support of northeastern clergy and their congregations. Thus Sharps Rifles sent by Henry Ward Beecher’s congregation became know as “Beecher Bibles”. Likewise, according to Potter, armed militias from the South began forming to support the pro-slavery cause in Kansas. (i)

Henry Ward Beecher (Source: Library of Congress Brady-Handy Photograph Collection (LC-BH82- 5388 A))

This post continues the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, and Part 4 here.

ABOUT THE POLITICAL CARTOON: Another Currier satire favoring American party candidate Millard Fillmore. A “buck” (James Buchanan) runs toward the White House, visible in the distance, as the two rival candidates take aim at him with their shotguns. Republican John C. Fremont’s gun explodes (left), as he struggles to free himself from a pool of “Black Mud.” On the far left his two abolitionist supporters Henry Ward Beecher and editor Horace Greeley are also mired in an “Abolition Bog.” Fremont: “Oh! Oh! Oh! I’ve got Jessie this time–” (a puzzling allusion to his wife Jessie Benton). Greeley: “Oh! Brother Beecher! our Kansas Gun has bursted and upset our gunner. I’m afraid we put in too big a load.” Reference is to the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 and the ensuing violence in Kansas, an issue exploited by the Republicans. Beecher: “Confound the Gun! if I can only get out of this muss I’ll stick to preaching and let fire-arms alone.” The oblique reference to Beecher’s part in outfitting armed antislavery emigrants for Kansas is made in more obvious terms in “Col. Fremont’s Last Grand Exploring Expedition in 1856” (no. 1856-20). On “Union Rock” (right), which is square in the path toward the White House, stands Millard Fillmore. He aims his flintlock at Buchanan and says confidently, “Ah! Fremont, your sectional Gun has exploded just as I predicted; but my American rifle will bring down that Old Buck.” MEDIUM: print on wove paper : lithograph ; image 24 x 39 cm. CREATED/PUBLISHED: N.Y. : Published at No. 2 Spruce Street, [1856] Source: Library of Congress

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 4

An illustration shows men lining up to vote on the issue of slavery in Kansas Territory. In 1855 voters chose to allow slavery. The Granger Collection, New York

The actual number of free-state settlers that made it to Kansas was far more modest than the expectations set in the press but the perception was in the public psyche.

Andrew Reeder

When the Kansas Territory’s first governor, Andrew Reeder, called for elections of the Kansas Territorial Legislature on March 30, 1855, pro-slavery Missourians crossed the border in droves and took advantage of a poorly conceived suffrage law that required little to no proof of residency to vote. The government they elected was widely recognized as bogus but Reeder let the election stand and President Franklin Pierce endorsed it. The new government created exceptionally pro-slavery laws, some verging on the absurd. Free-state men revolted by setting up their own shadow government in Topeka claiming that its laws and elected officials would become legitimate once statehood was achieved. This exacerbated further the rift between the two factions and opened the door for the Lecompton government to take legal action against the free-soil men, indeed eventually accusing some of treason.

“If one government was valid, the other was spurious, either morally or legally, as the case might be. If the acts of one were binding upon the citizens, then submission to the authority of the other by, for instance, paying its taxes or serving in its militia would constitute sedition, or even treason.” (i)

Polarization of the factions increased.

——

This post continues the series, “The Sacking of Lawrence May 21, 1856.” Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

(i) David M. Potter and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1976), 206.

The Sacking of Lawrence, May 21, 1856 – 1

Ruins of the Free State Hotel, Lawrence, Kansas. From a Daguerreotype. (The Kansas State Historical Society)

One of the most surprising things I learned from reading Michael F. Holt’s exceptional book, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s, was that the “Sacking of Lawrence” was not the murderous affair I had always thought it was. It led to further research on my part and the realization that I was guilty of combining the stories surrounding the raid on Lawrence with other violent events occurring in the region, an area in which I am a resident. As is often the case with history, I had developed a mythical sense of the day, one that went well beyond the simple destruction of property. This new post series summarizes the findings of my search for the truth about the events of May 21, 1856. Its writing helped to crystallize my understanding of why the Kansas and Missouri borderland became such a focal point for politics in the 1850s. It also revealed that there has been much liberty with the facts and that even today, historians do not agree on all of the specifics.

The Compromise of 1850: Effective Political Action or Forecast of Disaster?

Thanks to everyone that has participated in the Compromise of 1850 Poll going on here. If you haven’t voted, please do!

To expand the discussion, let me share my perspective on the question I raised, whether The Compromise of 1850 was an effective political action or a forecast of disaster.

The United States Senate, A.D. 1850. Drawn by P. F. Rothermel; engraved by R. Whitechurch. c1855. Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Number: LC-USZCN4-149

Michael F. Holt makes an excellent case in his classic, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s , that the Compromise of 1850 was more a forecast of disaster than effective political action. His argument is founded on the premise that the Compromise was effectively a deathblow to the Second American Party System and the notion that the health of America’s political parties in the mid-19th century was crucial to containment of sectional strife. As long as “men had placed their loyalty to their own party and defeat of the opposing party within their own section ahead of sectional loyalty, neither the North nor the South could be united into a phalanx against the other.” (1)

This conclusion is, of course, more easily arrived at when looking back at the period through the lens of generations with the full knowledge that the country would be ripped apart within fifteen years in a tumultuous Civil War. The perspectives of the politicians who negotiated the Compromise of 1850 would have, at the time, been much different. Indeed, they might have seen it as artful politics. The agreements made in the Compromise appeared to solve, at least temporarily, the country’s major ills which – on the surface – revolved around slavery and the country’s expansion.

But the effect was the displacement of the country’s trust in “party” as voice and defender of political views. The void caused men to affiliate more with their section, North and South. The scene was set for the country’s festering issues to rise again to a boil, this time without the benefit of cross-sectional parties that had so successfully contained discord in the past.

Thus my conclusion is that the Compromise of 1850 was BOTH an effective political action AND a forecast of disaster. It was effective for a time in that it allowed the country to continue forward with at least a fragile agreement on monumental issues. But its destruction of the Second American Party System led the country toward potential destruction.

And so…. what do you think? Comments welcome.

—-

See images of the original document – The Compromise of 1850 here.

(1) Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s, (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1983), 139.

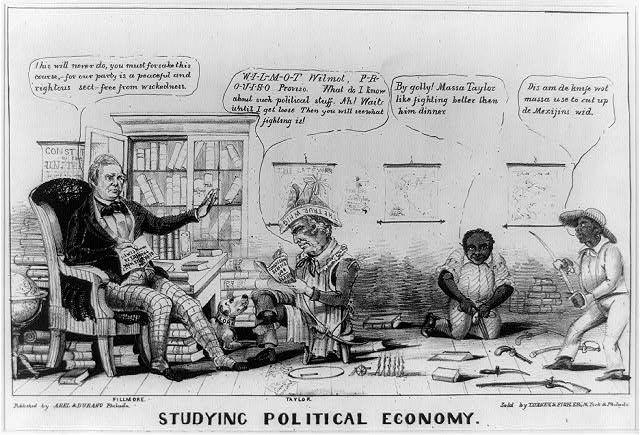

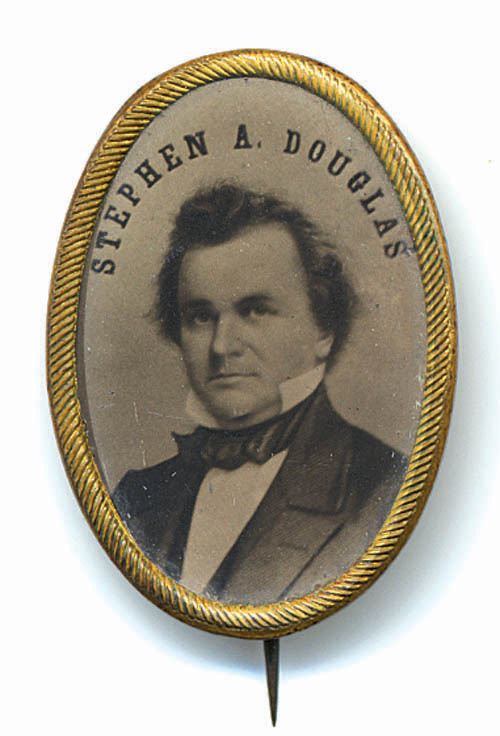

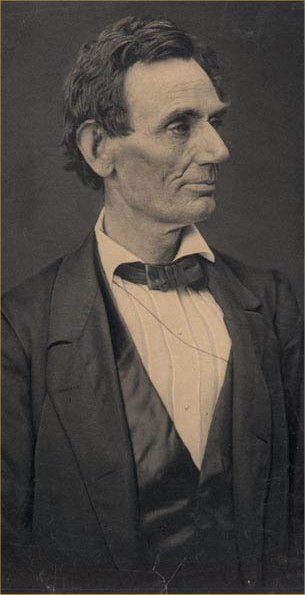

On Racism in the Antebellum North – 2 – Douglas

I recently had the opportunity to listen to a performance of the first four debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas. There is no better example of the Northern Antebellum perception of the black man than in the words of Douglas during the first of those debates held on August 21, 1858 in Ottawa, Illinois. He used the opportunity to mock Lincoln and abolitionists. More importantly, he showed his colors to be that of a true white supremacist. The comments from the crowd are noted in parentheses.

I recently had the opportunity to listen to a performance of the first four debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas. There is no better example of the Northern Antebellum perception of the black man than in the words of Douglas during the first of those debates held on August 21, 1858 in Ottawa, Illinois. He used the opportunity to mock Lincoln and abolitionists. More importantly, he showed his colors to be that of a true white supremacist. The comments from the crowd are noted in parentheses.

“I do not question Mr. Lincoln’s conscientious belief that the negro was made his equal, and hence is his brother, (laughter,) but for my own part, I do not regard the negro as my equal, and positively deny that he is my brother or any kin to me whatever. (“Never.” “Hit him again,” and cheers.) Lincoln has evidently learned by heart Parson Lovejoy’s catechism. (Laughter and applause.) He can repeat it as well as Farnsworth, and he is worthy of a medal from Father Giddings and Fred Douglass for his Abolitionism. (Laughter.) He holds that the negro was born his equal and yours, and that he was endowed with equality by the Almighty, and that no human law can deprive him of these rights which were guarantied to him by the Supreme ruler of the Universe. Now, I do not believe that the Almighty ever intended the negro to be the equal of the white man. (“Never, never.”) If he did, he has been a long time demonstrating the fact. (Cheers.) For thousands of years the negro has been a race upon the earth, and during all that time, in all latitudes and climates, wherever he has wandered or been taken, he has been inferior to the race which he has there met. He belongs to an inferior race, and must always occupy an inferior position. (“Good,” “that’s so.”)” (1)

Douglas also made a point of repeating in several of his debates with Lincoln the improprieties of an abolitionist who he observed driving a carriage while Fred Douglass lounged in the cab with the driver’s wife. This inflamed sense of impropriety regarding black men and white women was consistent with fear mongering in the South that led to greater controls on slave populations.

Read the first post in this series here.

(1) Abraham Lincoln, Stephen A. Douglas, “First Debate: Ottawa, Illinois August 21, 1858,” (<http://www.nps.gov/liho/historyculture/debate1.htm> Accessed on 18 Jan. 2009).

On Racism in the Antebellum North

"How you find yourself?" Source: Lithograph by Edward Clay, Life in Philadelphia, plate 4 (Philadelphia: S. Hart, 1829); courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia.

There is much in Bruce Levine’s Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of Civil War that informed my study of Antebellum America. Most of it fit with my understanding of the era and the issues with which Americans grappled. I gained much, however, from adding Levine’s insights to my own.

Several things stood out as surprising to me in my reading of Levine’s work. One epiphany came from Levine’s treatment of racism that existed in the North prior to the Civil War. It is easy for today’s generations to naively assume that since the North fought, in part, to end slavery, the peoples engaged in that effort felt some affinity for the black man. But Levine points out that “while deploring slavery as an institution,” many northerners “despised African Americans as much as southern whites did.” (1) But, Levine posits,

“Racism had a different significance in the free and slave states. Whereas in the South racism enlisted in the cause of keeping African Americans enslaved, in the North it aimed chiefly to force blacks out of the white population’s vicinity and path. Precisely because it served such very different practical ends, in different locales, antebellum America’s ubiquitous anti-black racism could not indefinitely reconcile northerners to southern demands and could not permanently calm slaveholders’ anxieties about northern intentions.” (2)

So while Northern religious and social values of the era were increasingly “antithetical to bondage,” they should not be interpreted as an invitation to the black man to fully join in Northern Antebellum white society.

About the image: The History Teacher provides an excellent description about this image in a larger lesson titled Free Black Activism in the Antebellum North and penned by Patrick Rael of Bowdoin College. He provides a description about the image that I believe will be helpful and which I quote here. I recommend a full reading of his essay which is available here.

“How you find yourself?”

Etchings such as this mocked the social pretensions of free black urbanites who, through their habits of consumption and display, were thought to desire social status above their stations. This image was one of a series, entitled “Life in Philadelphia” by political cartoonist Edward Clay, which lampooned the behavior of a range of city dwellers, white and black. The text on this image reads:Mr. Ceasar: “How you find yourself did hot weader Miss Chloe?”

Miss Chloe: “Pretty well I tank you Mr. Cesar[,] only I aspire too much!”The humor here, such as it is, depends on a malapropism, or a ludicrous misuse of words that signals their speaker’s inability to master proper English. This form of parody helped to define stereotypes of free blacks in nineteenth-century America, and continued well into the twentieth century.”

Image Source: Lithograph by Edward Clay, Life in Philadelphia, plate 4 (Philadelphia: S. Hart, 1829); courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia.

(1) Bruce Levine, Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of Civil War, Revised (Hill and Wang: New York, 2005), 251.

(2) Patrick Rael, “Free Black Activism in the Antebellum North,” The History Teacher February 2006 <http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ht/39.2/rael.html> (18 Jan. 2009).

New Acquisition: Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings & the Politics of the 1850’s

My copy of Tyler Anbinder’s Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings & the Politics of the 1850’s finally arrived yesterday. One of my readers recommended it as one of the best resources on the Know Nothings Party which I’ve just finished a series of posts on. Can’t wait to dig in.

ISBN13: 9780195089226

ISBN10: 0195089227

Paper, 352 pages

Oxford University Press

Published: May, 1994

Winner of the Avery O. Craven Award of the Organization of American Historians

New York Times 1992 Notable Book of the Year

Chosen by The Gustavus Myers Center as a 1992 Outstanding Book on Human Rights in the United States Outstanding Book on Human Rights

Dr. Anbinder is chair of the Department of History at The George Washington University. You can view his complete C.V. here.

Dr. Anbinder is chair of the Department of History at The George Washington University. You can view his complete C.V. here.

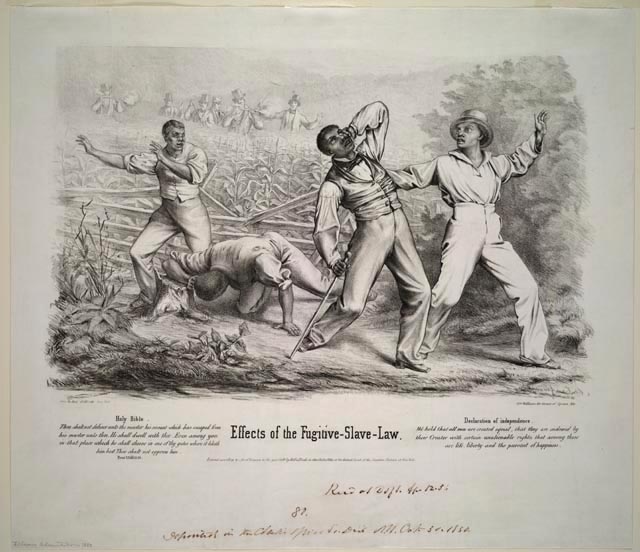

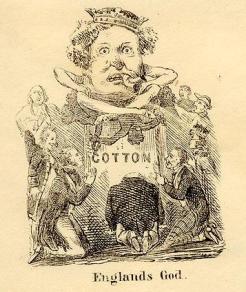

Fugitive Slave Law Backfires

Source: American Treasurers of the Library of Congress

Interesting reading from Bruce Levine’s text, Half Slave and Half Free : The Roots of Civil War, this evening. He contends that the fugitive slave law that was a part of the Compromise of 1850 actually did more damage to slavery’s cause than good.

So long as slavery seemed geographically contained and remote, free-state residents could despise it without feeling much direct personal involvement in its workings; slavery could thus remain the peculiar institution of the South, not a problem or responsibility of the North. By sending slave hunters into the free states and requiring even antislavery citizens to aid them, however, the new law made such rationalizations impossible.

Net-net: pushing compliance to slavery controls “compelled Northerners to confront slavery as a national, not just a sectional, issue.” (Levine, 189-190)

About the image:

S. M Africanus

The Fugitive Slave Law

Hartford, Connecticut: 1850

Printed broadside

Rare Book & Special Collections Division (33A)

In 1850, Congress passed this controversial law, which allowed slave-hunters to seize alleged fugitive slaves without due process of law and prohibited anyone from aiding escaped fugitives or obstructing their recovery. The law threatened the safety of all blacks, slave and free, and forced many Northerners to become more defiant in their support of fugitives. Both broadside and print, shown here, present objections in prose and verse to justify noncompliance with this law.

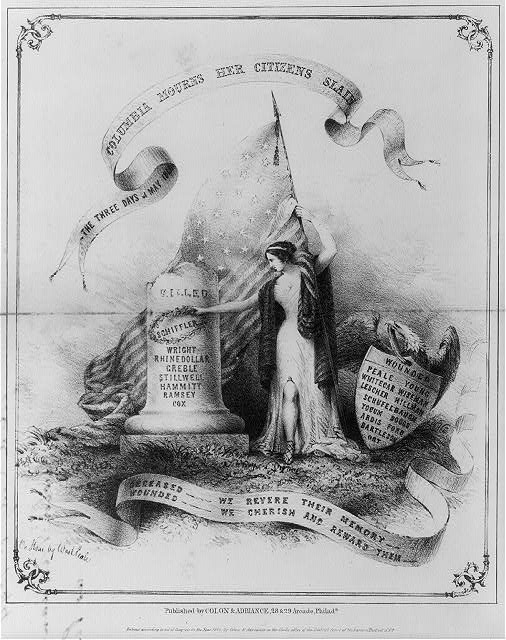

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 8

The three days of May 1844. Columbia mourns her citizens slain. Source: Library of Congress

Few would argue that a resurgence of nativism in the mid-19th century had a rational footing. It was, rather, “a nonrational response to contemporary problems” in “an age of social upheaval, an age of deprivation, stress, and imminent disaster.”

The nation was not facing civil war because of immigration from Ireland and Germany. The dislocations of urban-industrial growth were not produced by the newcomers, more victims than villains in this story. Attacking the Irish would not resolve the dilemma of sectional strife. Striking out at the aliens would not bring an end to socioeconomic changes or even the illusion of stability.

But embracing an antialien movement would allow frustrated nativists a sense of “escape from the central problems of their time. Unwilling to accept the dark side of their American experience—the wages of slavery, the stresses of a competitive culture, the crisis of community—they struck out at the most vulnerable group within their midst.” Thus Bennett posits, “the Know Nothing movement and the great appeal of nativism are found in concerns about immigration and historic fears of Catholicism.”

Many nativists thought the solution to the growing turmoil was to return to that which was familiar in the nation’s past, waging battle against an invading alien threat.

Americanists constructed a polarized world in which the enemy (now Catholic Irish and Germans) was an alien intruder and they were the “chosen people.”

In the end, Bennett asserts, the membership of the American Party would discover that “the issues over which they differed were as important as the religious, ethnic, and political bonds that united them.” Even though they achieved considerable early success as a party, they had not found a way to handle the great divisive issue of the day, slavery.

David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement , (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 94, 103, 119.

About the image.

A memorial to nativist casualties of the violent clashes occurring between anti-foreigner “Native Americans” and Irish-American Catholics in Kensington, Philadelphia, May 6 through 8, 1844. The female figure of Columbia holds a large, billowing American flag near a broken column on which she places a wreath. On the column are the names of those Native Americans killed during the attacks on Catholic homes and institutions. At the top of the list, circled by Columbia’s wreath, is the name of George Schiffler, the first and most famous of the nativist martyrs. Other names inscribed on the column are: Wright, Rhinedollar, Greble, Stillwell, Hammitt, Ramsey, and Cox. To the right of Columbia is an American eagle supporting a shield with the names of the wounded, including: Peale (the artist?), Whitecar, Lescher, Young, Wiseman, Willman, Schufelbaugh, Yocum, Ardis, Boggs, Ford, Bartleson, and Ort. Above the figure floats a streamer with the print’s title. Below a similar banner reads “Deceased—-We Revere Their Memory—Wounded—We Cherish And Reward Them—.”

Medium: lithograph on wove paper

Published by Colon & Adriance, 28 & 29 Arcade, 1844.

Library of Congress Call Number: LOT 10615-34 [item] [P&P]

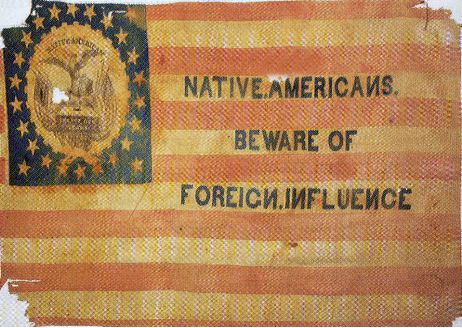

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 5

Flag of the Know Nothing Party

Historian James McPherson points out that the membership in the Know Nothings was “drawn primarily from young men in white-collar and skilled blue-collar occupations. A good many of them were new voters. One analysis showed that men in their twenties were twice as likely to vote Know Nothing as men over thirty.” (1)

Their leaders were also “new men” in politics who reflected the social backgrounds of their constituency. In Pittsburg, more than half of the Know-Nothing leaders were under thirty-five and nearly half were artisans and clerks. Know Nothings elected to the Massachusetts legislature in 1854 consisted mainly of skilled workers, rural clergymen, and clerks in various enterprises. Maryland’s leaders were younger and less affluent than their Democratic counterparts.” (1)

For more information on the Know Nothing Party in Massachusetts, see the Massachusetts Historical Society here.

(1) Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States), (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 135-136.

Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States), (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 135-136.

On Know Nothings and Secret Societies – 2

In the 1830s and 1840s, Americans had rediscovered a fascination with fraternalism discarded earlier in the century “when anti-Masonry led to public suspicion of secret societies.” (1) This was the era of the Odd Fellows, the Foresters, the Good Fellows and the Druids, the Red Men and the Heptasops. (2)

James McPherson marks the beginning of the movement that would lead to the “Know Nothing” American Party in the 1840s, when nativist parties flared and then cooled after the elections of 1844. (3) Relief from depression calmed tensions between native and foreign-born workers just in time for the massive influx of Europeans that resulted from that continent’s potato blight. (4) But American nativist sentiments continue to simmer and “on a late December evening in 1844, thirteen men gathered in the home of printer Russell C. Root in New York City” to form a group calling itself the American Brotherhood. The name was eventually changed to “Order of United Americans (OUA).” Its goals, outlined in a “code of principles,” were “to release our country from the thralldom of foreign domination.” This marked the birth of a nativist fraternity…and formed the nucleus of a far larger nativist effort than ever before. (5)

Membership in the Order of United Americans was limited to white men, twenty-one years of age or older, native born and Protestant. Its leaders were reasonably affluent and good organizers albeit from the “margins of the establishment.” This was a secret society replete with mysterious rituals and procedures that gave it an “illusion of antiquity.” (6)

Central to its structure was the magical triad. There were three levels of authority (local chapter, state chancery, and national archchancery), three chancellors sent from chapter to chancery, three archchancellors sent on to national. But there was only one leader of the OUA (limited to a single year term) and in the language of the lodge vogue he was called the arch grand sachem. By 1850, he ruled over a truly national domain with groups in New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Missouri, and Ohio. (6)

Gradually the organization began to become politicized and attracted “many conservative Whigs whose nativist ideology conveniently intersected with political needs in a time of party disarray.” (7)

—

1. David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 106.

2. Ibid.

3. James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 130.

4. Ibid.

5. David H. Bennett, The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History, 105.

6. Ibid, 107.

7. Ibid., 110.

Political History Word of the Day – Jingoistic

I ran across the word “jingoistic” tonight in my reading of a fascinating book, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement by David H. Bennett.

I ran across the word “jingoistic” tonight in my reading of a fascinating book, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement by David H. Bennett.

jingoistic

adjective

fanatically patriotic [syn: chauvinistic]

jin·go·ism

Extreme nationalism characterized especially by a belligerent foreign policy; chauvinistic patriotism.

jin’go·ist n., jin’go·is’tic adj., jin’go·is’ti·cal·ly adv.

Here is a snippet from Bennett’s book to show the context of his use of the word.

The greatest upheaval was the clash between the North and South. The issue of slavery, and the sectional conflict it helped to generate and exacerbate, was inextricably connected to territorial expansion. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 temporarily resolved that issue, setting the famous line (36° 30″) to the Pacific, north of which the South’s “peculiar institution” could not be extended. But the question flared anew with the Mexican War and the prospect of a rich California territory and a new estate in the desert and mountain West available for American settlement and development. This war of expansion did not unify the country as have international conflicts in some tranquil times. Nor did that other jingoistic outburst against the British in the debate over division of the Oregon territory in the far Northwest. (2)

(1) jingoistic. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/jingoistic (accessed: December 20, 2008)

(2) David H. Bennett, The Party Of Fear: The American Far Right from Nativism to the Militia Movement [book on-line] (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988, accessed 20 December 2008), 95; available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=105437276; Internet.

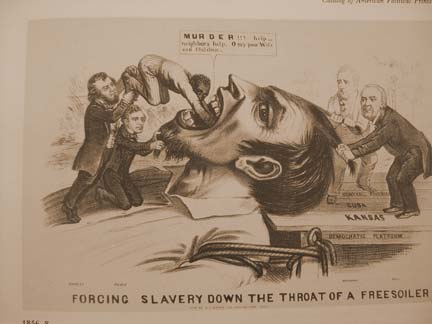

On Free Soilers – 2

A key reason that “Free Soilers” feared the South, and particularly slaveholders, was because of the political power they wielded in the national parties and government. This resentment found as “epithet the term ‘Slave Power,’ which Northern politicians of both parties used to denounce the political pretensions of slaveholders. Prohibiting slavery from the territories was the easiest way to prevent the admission of more slave states and thus to stop the growth of the political power of slaveholders.”(1)

Fear of the South’s power manifest itself in the resentment and writings of politicians such as David Wilmot (Wilmot Proviso).

“I am jealous of the power of the South….The South holds no prerogative under the Constitution, which entitles her to wield forever the Scepter of Power in this Republic, to fix by her own arbitrary edit, the principles of policy of this government, and to build up and tear down at pleasure… Yet so dangerous do I believe the spirit and demands of the Slave Power, so insufferable its arrogance, if I saw the way open to strike an effectual and decisive blow against its domination at this time, I would do so, even at the temporary loss of other principles.” (1)

Even within parties there was resentment between North and South. Michael Holt provides a quote from a young Massachusetts Whig that shows the visceral nature of the resentment of Northerners toward their party colleagues from the South.

“They have trampled on the rights and just claims of the North sufficiently long and have fairly shit upon all our Northern statesmen and are now trying to rub it in and I think now is the time and just the time for the North to take a stand and maintain it till they have brought the South to their proper level.” (1)

While the reasons for this resentment were complex, one clear fear was that the South would dictate the expansion of slavery into Western territories and this would degrade the value of free white labor and thus the potential for movement of the Northern-based labor ethic into those territories.

(1) Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850’s, (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1978), 51.

The Cycles of History: The Panic of 1857

Interesting insights this morning from Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War by Eric Foner. I’ll let you draw your own parallels to our current challenges.

“As they were to do many times subsequently, Republicans blamed the Panic not on impersonal economic forces, but on the individual shortcomings of Americans, particularly their speculation in land and stocks which had reached ‘mania’ proportions in the years preceding the crash, and on generally extravagant living. The Cincinnati Gazette defined the basic economic problems as an overexpansion of the credit system, rooted in too many ‘great speculations.’ But speculation was only one aspect of the problem of general extravagance. ‘We have been living too fast,’ complained the Gazette. ‘Individuals, families, have been eagerly trying to outdo each other in dress, furniture, style and luxury.’ The Chicago Press and Tribune likewise blamed ‘ruinous extravagance’ and luxurious living’ for the economic troubles, and both papers urged a return to ‘republican simplicity,’ and the frugal, industrious ways of the Protestant ethic.”

Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). 24.

On Slavery 9 – Partus Sequitur Ventrem

When considering slaves, Colonial Virginians abandoned the English tradition of partus sequitur patrem (one’s status was determined by the disposition of their father) in favor of the Roman principle of partus sequitur ventrem, a “child inherits the condition of the mother.” (1) Thus offspring of slave women were the property of their mother’s owner whether fathered by freeman or not. Annette Gordon–Reed, in her book “The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family,” speculates on why Virginian colonists made up this particular form of slavery that endured until the Civil War.

“White men, particularly the ones who made up the House of Burgesses, the legislature in colonial Virginia, were the masters of a growing numbers of African women, owning not only their labor but their very bodies. That these women sometimes would be used for sex as well as work must have occurred to the burgesses. Inevitably offspring would arise from some of these unions. Even white males who owned no slaves could contribute to the problem by producing, with enslaved black women, children who would be born free, thus destroying a critical component of the master’s property right: the ability to capture the value of the “increase” when female slaves gave birth.” (2)

Gordon-Reed goes on to describe an actual court case that occurred in 1655 in which Elizabeth Key, a woman of mixed blood, “successfully sued for her freedom on the basis of the fact that her father was English.” (3) This ruling, if left to stand as precedent, would have created a gap by which a growing number of children could escape slavery, those fathered by free white men and black women in bondage.

The impacts were staggering. First, the law “assured that white men – particularly the privileged ones who passed the law, who would not likely have been hauled into court for fornication even with white women – could have sex with enslaved women, produce children who were items of capital, and never have to worry about losing their property rights in them.” (4)

Gordon-Reed suggests that the law was likely intended to reduce racial-mixing in that along with it was passed a measure that increased the fines for mixed-race couples that engaged in sex out of wedlock. But in effect, it meant “the private conduct of men would have no serious impact on the emerging slave society as a whole. White men could engage in sex with black women without creating a class of freeborn mixed-race people to complicate matters.” (5)

Second, the law implied that every person suspected of having African blood, was assumed to be a slave unless they could prove otherwise. “…The English common-law presumption in favor of freedom did not apply to Negroes; in all slave states (except Delaware) the presumption was that people with black skins were slaves unless they could prove that they were free.” (6) Kenneth Stampp explains that this hyper race sensitive system required that “the offspring of a free white father and a Negro, mulatto (half), quadroon (one Negro grandparent), or octoroon (one Negro great-grandparent) slave mother was a slave.” (7) This ruling once again encouraged exploitation of women in that mixed-blood, often very white appearing women, were kept as slave prostitutes to service white men.

Paradoxically, the child of a black enslaved father and a free white mother was considered by law in most states, free. Likewise, children found to have descended from a female Indian were considered free because, with the exception of a short time in the 17th century, it was unlawful to enslave an Indian.

Paradoxically, the child of a black enslaved father and a free white mother was considered by law in most states, free. Likewise, children found to have descended from a female Indian were considered free because, with the exception of a short time in the 17th century, it was unlawful to enslave an Indian.

As might be imagined, interpretation of the rules governing race and thus one’s status as property varied by locale. “In Alabama a ‘mulatto’ was ‘a person of mixed blood, descended, on the part of the mother or father, from negro ancestors, to the third generation inclusive, though one ancestor of each generation may have been a white person.” (8) South Carolina didn’t specifically define terms such as Negro and mulatto but left interpretation to visible evidence of mixture and took into account “a person’s reputation among his neighbors.” (9) One was considered free in Kentucky if it could be proven that one had “less than a fourth of African blood.” (10)

The legacy of the men who created a country built upon laws that supported racial slavery was in part the creation of a culture that expended a great deal of energy establishing the racial status and thus property rights to a growing population of mix-blood “chattel personal.” It was a legacy that encouraged widespread abuses and the flagrant misuse of female slaves who had no legal rights at all. As contended by Gordon-Reed, “under the rules of the game the burgesses constructed,” there was no need to interfere with other men’s conduct. Whatever the social tensions and confusion created by the presence of people who were neither black nor white, Virginia’s law on inheriting status through the mother effectively ended threats to slave masters’ property rights when interracial sex produced children who confounded the supposedly fixed categories of race.” (11) Hyper-race sensitivity and all its implications would continue for centuries to come.

For more information on Elizabeth Key’s freedom case, see a paper by Taunya Lovell Banks from the University of Maryland School of Law, “Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key’s Freedom Suit – Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth Century Colonial Virginia” here.

(1) Kenneth M. Stamp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South, (New York: Vintage Books, 1956), 193.

(2) Annette Gordon – Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008), 46.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Ibid., 46-47.

(6) Kenneth M. Stamp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South, 193-194.

(7) Ibid., 194.

(8) Ibid., 195.

(9) Ibid.

(10) Ibid., 196.

(11) Annette Gordon – Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, 47.

On Slavery – 8: The “Peculiar Institution”

I believe the use of the phrase “peculiar institution” was intended to convey the highly contradictory nature of the practice of human ownership in a country based on equality and freedom. Regardless of what perspective one might have of slavery in America, it is difficult to argue against the fact that these contradictions existed. Historian Kenneth Stampp’s chapter titled “Between Two Cultures,” in his book, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South, provides several compelling examples.

1. American culture was heavily influenced by religion and yet the South used that religion to justify slavery.

2. Morality of the day frowned on fornication and yet the laws of the day prohibited slaves from legally marrying, thus not only condoning but also encouraging slaves to live out-of-wedlock. Slave owners preached “virtue and decency…” but then wondered why there was widespread sexual promiscuity. Add to this the “hypocrisy in white criticism of their moral laxity” when masters used their slaves “to satisfy an immediate sexual urge.”

3. Rape of a white woman by a slave was punishable by death but “no such offense against a slave woman was recognized in law.”

4. The family was critically important to white culture but the “peculiar institution” condoned the intentional undermining of normal family structures among bondsmen because it best suited their owner’s economic goals as well as furthering command and control of laborers. “The family had no great importance as an economic unit.” And the Protestant South was highly tolerant of slave owners who separated spouses and families.

5. Stampp points out that “the enterprising, individualistic, freedom-loving, self-made man” attained the greatest respectability in white society of the 19th century. And yet slaves were given no opportunity to even hope to aspire to this level of respectability.

6. Rather than a society based on equality, the South developed a highly stratified caste system.

And so I contend that embracing slavery left the South at odds with itself, the North, and much of the rest of the world. And yet embrace it, it did. Use of the phrase “peculiar institution” instead of “slavery” was yet another way in which the South struggled to reconcile the irreconcilable.

Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South.

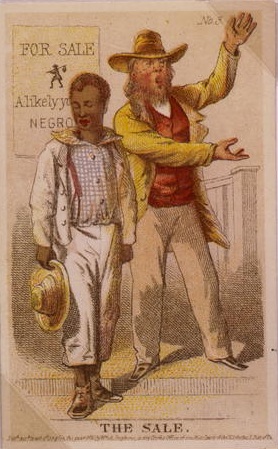

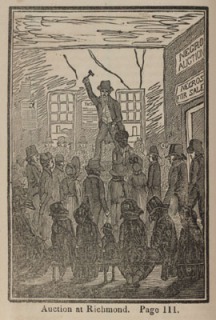

On Slavery – 7 Slavemongering

Green Hill Plantation, Slave Auction Block, State Route 728, Long Island vicinity, Campbell County, VA Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Many words lose their relevance and thus usage over time. Fortunately, slavemongering, is among them.

A monger is defined as a dealer or trader. To monger is to promote or deal in something specified. It is generally used in a composition. Thus a costermonger is an itinerant fruit-seller, a fellmonger is a dealer in skins, a fishmonger peddles fish, and an ironmonger is a dealer in iron goods.

Walter William Skeat’s An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, suggests as possible source of the word.

monger, mangere a dealer merchant formed with suffix ere from mang ian – to traffic barter gain by trading.

The relationship to the Lat[in] mango, a dealer in slaves, is not clear but the [English] word does not appear to have been borrowed from it. [1]

Slaves were “inseparable from any species of private property” and since “titles to slaves were transferable,” their owners had the power of conveyance. [2] Thus the legality of slavemongering, or the trafficking of slaves, was firmly established in the Antebellum South.

Slave owners seemed somewhat ambivalent to the idea of slavemongering. Some despised the idea but took advantage of it non-the-less. Thus one who found the sale of a bondsman distasteful or even bordering on amoral, could unburden themselves of their human property using a professional.

Franklin & Armfield had the distinction of being the the largest slave-trading enterprise in the South at least during the period prior to the Panic of 1837. Formed in 1828, its principles were John Armfield and Isaac Franklin. They each “accumulated fortunes in excess of a half million dollars” before retiring. [2]

Hundreds of small entrepreneurs engaged in slave trade but only a few made large sums of money. Among these few was Nathan Bedford Forrest who “was the largest slave trader in Memphis during the late 1850’s; he was reputed to have made a profit of $96,000 in a single year.” [2]

[1] Walter William Skeat, An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, accessed on the internet via Google Books, November 22, 2008 here.

[2] Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South.

On Slavery – 6 Chattels Personal

Kenneth Stampp’s chapter “Chattels Personal” is excellent. I suspect that “chattel” is not a word most of us learn unless we study law or Antebellum American history in depth. Its meaning in the context of slavery is, of course, that person’s slaves were consider legally as “chattel personal.”

Being a person quite taken with words, I did a little research on the origins of this one and found it informative. Interestingly, a search for the etymology of the word found some disagreement. The following perspective comes from French: A Linguistic Introduction.

“Chattel comes from the French noun cheptel used to designate all movable property, but now is restricted to ‘livestock’. English has gone a step further: cattle used to designate any movable property, then all livestock, and now is generally restricted to bovines. English also has the word chattel, legally any type of movable property, but more specifically in modern usage, it refers to slaves. All of these terms are ultimately derived from the Latin word capitalis, which has been reintroduced in modern financial vocabulary, e.g. capital campaign in fundraising. This term, in turn, is derived from the Latin word caput, ‘head’ (French chef), with the result that ‘head of cattle’, our original example, ultimately is a ‘head of things with heads’!” [1]

This from A New Law Dictionary and Glossary…

“…the singular chattel seems to be immediately formed from the Fr. chatelle, or chatel, (q.v.); the plural chattels, (or, as it was formerly written, catals,) is supposed to be derived from the L. Lat., catalla, the ch being pronounced hard, as in the word charta, which is evident from the form of the old Norman plural, cateux, (q.v.). As to any further derivation, catalla or catalia is clearly shown by Spelman to be merely a contracted form of writing capitalia, which with the singular capitale, or captale, occurs frequently in the Saxon and early English laws. The primary meaning of capitalia was animals, beasts of husbandry, (otherwise call averia, q.v.) or cattle; in which last word it is still identically retained.

Capitalia is derived by Spelman from capita, heads; a term still popularly applied to beasts, as “so many “heads of cattle.” When the word took the form catalla, it continued to retain this primary meaning, but gradually acquired the secondary sense of movables of any kind, inanimate as well as animate, and finally became used to signify interests in lands.”

CHATTELS PERSONAL, otherwise called THINGS PERSONAL, comprise all sorts of things movable, as good, plate, money, jewels, implements of war, garments, animals and vegetable productions; as the frit or other part of a plant, when severed from the body of it, or the whole plant itself, when severed from th ground. Besides things moveable, they include also certain incorporeal rights or interestes, growing out of, or incident to them, such as patent rights and copyrights…” [2]

——

[1] French: A Linguistic Introduction

By Zsuzsanna Fagyal, Douglas Kibbee, Fred Jenkins

Published by Cambridge University Press, 2006

ISBN 0521821444, 9780521821445

337 pages (pp. 154-155), Accessed online, November 16, 2008, http://books.google.com/books?id=4yTA6SvGuekC&pg=PP1&dq=French:+A+Linguistic+Introduction#PPA154,M1

[2] A New Law Dictionary and Glossary

By Alexander M. Burrill

Published by The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 1998

ISBN 1886363323, 9781886363328

1099 pages (pp. 207-208), Accessed online, November 16, 2008, http://books.google.com/books?id=DeQYXYMBtwgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=etemology+of+the+word+chattel#PPA208,M1

Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South.

On Slavery – 4

Cotton Harvest, U.S. South,1850s Reference BLAKE4, as shown on http://www.slaveryimages.org, sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library.

The experience of slaves could vary by region due in large part to the type of product the slave was engaged in bringing to market. Slaves in the hemp producing regions of Kentucky and Missouri, worked in rhythm with the cycles required by the crop. Similarly, slaves who worked in cotton producing areas (above) or regions in which tobacco was cultivated, would have had daily and seasonal work routines aligned with those crops. Regional weather would also have differentiated the experience of slaves in different parts of the south.

Slaves rented out to work in industrial areas with factories would have had a decidedly different experience than those working on a plantation. Author Kenneth Stampp suggests that factory slaves enjoyed more freedom and yet an equal if not higher incidence of overwork. The daily experience of slaves living in urban centers would have been decidedly different than rural slaves. Domestic assignments were not uncommon.

On Slavery – 3

[This post continues the series On Slavery (1 here and 2 here).]

"Flogging the Negro" (Cropped) Full Image Reference NW0213, as shown on http://www.slaveryimages.org, sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library.

Kenneth Stampp in his book, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South, suggests that some owners of slaves were conflicted about the need to apply punishment in the control of slaves and yet most felt fully justified in imposing that control. He sites on numerous occasions the willingness of owners to overlook the cruelty of overseers if they met or exceeded production goals. This head-in-the-sand approach to ethics undoubtedly had many causes but the most obvious was greed.

Owners also considered their slaves to have a “duty” to their master by virtue of the fact that they were, after all, his property and that the master provided and cared for them. But the most prevalent justification for imposing control on the slaves was to achieve maximum production from them as a labor force. Poor performers, for whatever reason, were seen as impacting the bottom-line.

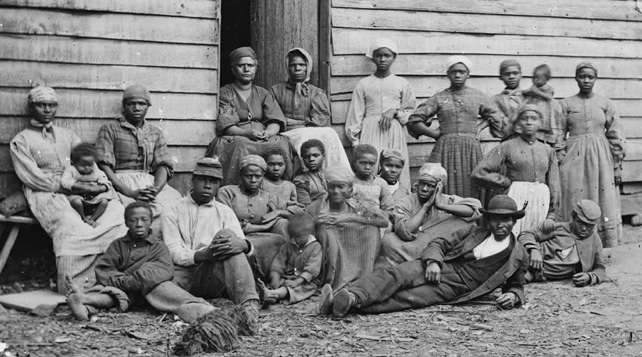

On Slavery – 1

Photograph of Slave Cabin and Occupants Near Eufala, Barbour County, Alabama (Photo source: Library of Congress)

I’m reading Kenneth M. Stampp’s fascinating book, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South for class. A focus this week and next is, among other things, the ways in which slave owners controlled their bondsmen. The methods varied considerably as did the ethical sensibilities of the masters and overseers. Stampp suggests that behavioral control included both the carrot and the stick with heavy weighting on the stick. That is to say, some masters and/or overseers used positive incentives and some negative.

Positive incentives included: work stoppage at noon on Saturdays and Sunday off, holidays off, parties and dances, holiday gifts, cash for the best worker for a given period, the right to grow one’s own crops whether for personal food or sale, the right to rent oneself out and keep some of the income, and the ultimate incentive, the right to achieve freedom.

Negative incentives were many. Stampp suggests that few adult slaves did not have some experience with flogging. This seemed to be the most acceptable method of disciplining slaves and was used extensively. Other forms of physical punishment used to control slaves included: confinement either in “the blocks” or even jail, mutilation (ranging from castration to branding), and even more severe forms of torture. For young slaves or those who needed “breaking,” there were actually specialists who through, undoubtedly mental and physical persuasion, reduced high spirited individuals to more pliable and subservient workers.

Another method of control was the introduction of religion to the slaves. Indoctrination of slaves into Christianity had its advantages. It was not uncommon for them to ensure that sermons emphasized those verses in the Bible that instructed servants to obey their masters. (Stampp, 158) Particular focus was made on teaching slave children “respect and obedience to their superiors” in the belief that it made them better servants. (Stampp, 159) This suggests a fascinating area of study – the effects of religion on American slaves – for which I must look for information. Let me know if you can recommend any.

Next Class: Antebellum America: Prelude to Civil War

After a short break, I’ll be diving into my next class which starts November 3rd. As is my custom, I’ve added this to “The Courses” page.

“Antebellum America: Prelude to Civil War” (starts November 3rd)

This course is an analysis of the conditions existing in the United States in the first half of the 19th century. The course focuses on the political, cultural/social, economic, security, leadership, and other issues that played roles in starting and shaping the Civil War. We will analyze the issues in the context of war and peace to determine whether or not such conflicts as civil wars can be avoided prior to their inception.

Required Texts:

TBD once the syllabus is available. For now, the list is as follows which is very light in comparison with my last class:

Publisher: W. W. Norton and Company

Publisher: W. W. Norton and CompanyHalf Slave and Half Free : The Roots of Civil War by Bruce Levine

Road to Disunion : Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854, Volume 1 by William W. Freehling

Book Report: George Bancroft

I realize this won’t be for everyone but I wanted to post the academic book review I finished yesterday on the paperback version of Russel Blaine Nye’s 1945 Pulitzer Prize winning biography George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel. Sadly this book is out-of-print and available only via library or used book markets. It is a fascinating work filled with insights into an uncommon man who was once this country’s most revered historian – but whom most of us have no memory. It also provides considerable information about our country – and indeed the world – in the period leading up to, during and after the Civil War.

It was enlightening to put this post together in that I discovered some great sources of information about many of the people, places and times in which Bancroft lived. Kudos to http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org for their information on important persons in that university’s history.

By Russel B. Nye. New York

(Washington Square Press, Inc.). Pp. 212. 1964. $.60

If biographies written in the twenty-first century tend toward tomes, Russel Nye’s work on George Bancroft, easily the most acclaimed American historian of the nineteenth century, demonstrates how to impress with a modicum of words. Bancroft’s life spanned a period of epic change in the fledgling American nation. Nye skillfully paints a portrait of the man against the sweeping landscape of the United State’s passage from fledgling country at the turn of 18thcentury to a battle-scarred nation ninety years later. Bancroft helped to make American history as politician and statesman. He also became one of the country’s most gifted historiographers and the first popular historian, a title that was, by the end of the century, not unlike his literary writing style, considered “passé.”

George Bancroft came from a legacy of northeastern conservatism. Bred squarely into the center of the American Calvinistic farming culture of Worcester, Massachusetts, his grandfather Samuel Bancroft was both strict Calvinist and independent of mind. Bancroft’s father, Aaron Bancroft, had a noteworthy career as one of the first leaders of the Unitarian movement. This step toward liberalism directed him to the pastorship of a small Second Congregational Church of Worcester and modest means to support his growing family. But it also positioned him with the intellectual elite of New England. The Bancroft home was a place where books were plenty and reading and discussion encouraged. Independent reason was also valued. Aaron Bancroft authored one of the more popular biographies of George Washington, a man who young George Bancroft would eventually count as among the most influential hero-leaders of the country.

George stood out among his siblings and opportunities were given to him to attend preparatory school at a young age even though it caused strain on his father’s finances. He excelled and passed entrance exams to Harvard College at the  age of 13. Bancroft graduated Harvard at 17 and, with the assistance of college president John Thornton Kirkland (pictured right and papers here), w

age of 13. Bancroft graduated Harvard at 17 and, with the assistance of college president John Thornton Kirkland (pictured right and papers here), w as provided both financial support and the necessary letters of introduction to follow a select few Harvard graduates to Göttingen, one of the top universities in Germany (brief history of the town and university here). His goal was to follow his father into the ministry. He began a rigorous course of study including a self-imposed schedule of sixteen hour days. By the age of twenty, Bancroft had a Göttingen doctorate and the respect of some of Germany’s most noted professors. But he had also developed a considerable interest in philosophy, history and literature and began to doubt whether a career in the ministry remained his passion. He continued with post doctorate studies in Berlin and by the end of his four years in Europe had met many of its influential writers, artists and academics. Bancroft returned home filled with ideas about educational reform and exhibiting mannerisms and dress inspired by his time abroad.

as provided both financial support and the necessary letters of introduction to follow a select few Harvard graduates to Göttingen, one of the top universities in Germany (brief history of the town and university here). His goal was to follow his father into the ministry. He began a rigorous course of study including a self-imposed schedule of sixteen hour days. By the age of twenty, Bancroft had a Göttingen doctorate and the respect of some of Germany’s most noted professors. But he had also developed a considerable interest in philosophy, history and literature and began to doubt whether a career in the ministry remained his passion. He continued with post doctorate studies in Berlin and by the end of his four years in Europe had met many of its influential writers, artists and academics. Bancroft returned home filled with ideas about educational reform and exhibiting mannerisms and dress inspired by his time abroad.

Bancroft spent the next several years trying to find his calling. Trained in philology (the study of languages) as well as theology, he tried on the role of Greek tutor at Harvard but became frustrated with the college’s lack of interest in adopting the new educational techniques he brought from abroad. He was also unpopular as a teacher, which is not to say that he was a bad teacher; rather a demanding one. By mutual consent, he left Harvard after a year and with fellow Harvard and Göttingen graduate Joseph Cogswell, opened the Round Hill School for boys near Northampton, Massachusetts in 1823. It became a phenomenon of sorts due to the melding of the latest methods of European educational reform with those of American boarding school. “It was one of the earliest and most successful efforts of the nineteenth century to raise the level of American secondary education by absorbing the new European experimentation, and served as a powerful influence in the diffusion of new ideas on discipline, individual attention, and stimulation of student interest” (45). A student was treated as an individual with unique learning patterns and cooperated as an equal with his teacher rather than as an inferior with his master. Despite the demanding program, the elite of New England clamored to enroll their sons. With Bancroft as the primary teacher and Cogswell managing administration, the school grew in both size and reputation.

It was at Round Hill School that Bancroft met his wife, Sarah Dwight. Her status as the daughter of a wealthy New England family would ensure his financial independence. Bancroft also continued to work on his poetry (he had published Poems while at Harvard) and found opportunity for preaching. But he was successful at neither. His poetry was labeled amateurish and his oration at the pulpit “too consciously learned, too pretentiously oratorical” (5). Interestingly, Bancroft would become a gifted literary critic. A man of many interests, he became bored with the life of a country school teacher and bowed out of the venture in 1831. The Round Hill School failed three years later.

Bancroft discovered while at Round Hill a growing interest in politics. He began to write for prominent journals and even spoke in a political forum in Northampton at the behest of town leaders. In 1830 he was nominated for the Massachusetts’s senate by the Workingmen’s party. Although he declined, his voice as a political philosopher began to emerge. It was firmly centered on the premise that the will of the many outweighed that of the few, a principle that he considered foundational to democracy. He clearly identified himself as a Jacksonian democrat in 1836, a fact that surprised a number of his Whig Harvard colleague s including friend Edward Everett (pictured right). His allegiance was with the common, agrarian masses rather than the privileged minority. His political position became all the more public with Bancroft’s growing involvement in the Democratic Party. He wrote several journal articles in support of Jackson’s position on the national banking issue which he attributed to the long struggle between capitalists and laborers. In 1838, his party work was rewarded with the position of Collector of the Port of Boston. By 1844, he was a prominent player in the Massachusetts democratic delegation and played a key role in securing the Presidential nomination for

s including friend Edward Everett (pictured right). His allegiance was with the common, agrarian masses rather than the privileged minority. His political position became all the more public with Bancroft’s growing involvement in the Democratic Party. He wrote several journal articles in support of Jackson’s position on the national banking issue which he attributed to the long struggle between capitalists and laborers. In 1838, his party work was rewarded with the position of Collector of the Port of Boston. By 1844, he was a prominent player in the Massachusetts democratic delegation and played a key role in securing the Presidential nomination for  James K. Polk (pictured left). Polk appointed Bancroft Secretary of the Navy the following year and he found himself Acting Secretary of War during the months that opened the Mexican War. But Bancroft was after a diplomatic post and between 1846 and 1849 he served as United States Minister to England. It was during this time that he amassed a huge collection of historical notes from British archives, utilizing scribes and secretaries to copy copious amounts of data. These he brought home to America for use in future historical writing.

James K. Polk (pictured left). Polk appointed Bancroft Secretary of the Navy the following year and he found himself Acting Secretary of War during the months that opened the Mexican War. But Bancroft was after a diplomatic post and between 1846 and 1849 he served as United States Minister to England. It was during this time that he amassed a huge collection of historical notes from British archives, utilizing scribes and secretaries to copy copious amounts of data. These he brought home to America for use in future historical writing.

The scholar in Bancroft had found new voice shortly after leaving Round Hill. In 1834, he published the first of what would become his multi-volume treatise, A History of the United States from the Discovery of the Continent (set of all volumes to right). (A full listing of Bancroft’s works avail able online can be found here.) He chose to focus not on contemporary history but rather on the formation and evolution of the nation. Bancroft believed that the creation of the United States of America was part of a divine plan. It was a demonstration for all the world of the efficacy of a nation built on the principles of liberty.

able online can be found here.) He chose to focus not on contemporary history but rather on the formation and evolution of the nation. Bancroft believed that the creation of the United States of America was part of a divine plan. It was a demonstration for all the world of the efficacy of a nation built on the principles of liberty.

Pivotal to the country’s success was the quality of its leaders. “The secret of the science of governing, Bancroft decided, lay in the quality of a nation’s leaders – those great men who personify the people’s ideals, act out their interests, and crystallize their needs in laws and institutions” (82). Nye found that Bancroft valued two types of hero-leaders. The first was the agrarian nobleman best exemplified in Andrew Jackson (pictured below).

His gift was an innate perceptiveness gained from long connection with nature. The second was the classic wise man whose traits Bancroft found in George Washington, a man for whom he had a lifelong admiration.

Abraham Lincoln eventually became Bancroft’s third hero-leader. While initially unimpressed with Lincoln, his respect for him grew to such a degree that he eventually thought him representative of the genius of the American people. Bancroft’s regard for Lincoln was no doubt one reason that he was chosen by Congress to deliver his eulogy. It was considered his best oration.

Like the nation, Bancroft had to come to terms with slavery. He blamed the English for its introduction to the colonies and thought it a temporary evil gone array. Its conflict with the principles of liberty was always obvious. While never a flaming abolitionist, Bancroft considered slavery the primary cause of the Civil War and spoke out about it primarily in his writing. He was a resolute unionist and had little sympathy for arguments for state rights and for the succession movement.

Bancroft happily finished his diplomatic career in Germany where he became a favorite of politicians and intellectuals. He returned to a quite life, still writing and active for most of his ninety-one years. The portrait below was painted while Bancroft was in diplomatic residence in Germany.

Nye does a masterful job of identifying Bancroft’s core beliefs and the influences that formed the man and his career. He also shows a considerable grasp of the nuances of history that were in play in the 19th century, worth noting because Nye’s training is in literature rather than history. His obvious mastery of the large collection of papers Bancroft left behind for his biographers is impressive.

Nye leaves the reader with a sense for the utter brilliance of Bancroft (pictured below in his study) and yet presents him as anything but infallible. He was a man who enjoyed the privileges of an education well beyond the norm of his day and earned by an innate drive and love for scholarship. He was comfortable with life choices that went ag ainst the norm, an indication of independence of thought. He was not unfamiliar with loss, having endured the death of his young wife. He knew failure, having disappointed those who saw in him potential as minister. His failure as a poet, a personal aspiration, revealed a level of sensitivity (He worked very hard to find and destroy every copy of his Poems.). He embraced cultures and perspectives outside of his own and yet remained an American patriot. He brought to his generation a better sense of the story of their country and to a large degree, popularized history. He remained a loud voice for the ideals of liberty and democracy and the rights and privileges of the masses. But at his core, he was, as depicted by Nye, a man of letters and I suspect that Mr. Bancroft would be pleased with that distinction. His legacy is a remarkable body of work sadly forgotten by most citizens of the 21st century.

ainst the norm, an indication of independence of thought. He was not unfamiliar with loss, having endured the death of his young wife. He knew failure, having disappointed those who saw in him potential as minister. His failure as a poet, a personal aspiration, revealed a level of sensitivity (He worked very hard to find and destroy every copy of his Poems.). He embraced cultures and perspectives outside of his own and yet remained an American patriot. He brought to his generation a better sense of the story of their country and to a large degree, popularized history. He remained a loud voice for the ideals of liberty and democracy and the rights and privileges of the masses. But at his core, he was, as depicted by Nye, a man of letters and I suspect that Mr. Bancroft would be pleased with that distinction. His legacy is a remarkable body of work sadly forgotten by most citizens of the 21st century.

American Military University

Rene Tyree

Good Discussion on the Inevitability of the Civil War

The final post of my series Exploring Causes of the Civil War (which you can read here) titled “The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability,” has spawned some interesting debate over both the inevitability of the Civil War and the idea of “inevitability” itself. Blogger Elektratig not only provides some insightful comments to my post, but expounds upon those in a post titled “Historical Inevitability” on his own blog here. He provides a good argument that rather than “inevitability,” we should speak of “probability.”

John Maass (a fellow wordpress.com blogger at A Student of History) enters the discussion with the assertion that looking at historical events as “inevitable” is amateurish history (see comments on both my original post and on Elektratig’s) and is particularly dangerous in the field of military history because of the contingencies that can come into play during war.

It promotes a teleological view of history that is simply far too unsophisticated and “cookie cutter” for an accurate look at the past. Anyone can go back into the chronicle of the past and see lots of events and add them all up to “prove” that a subsequent event was inevitable or foreordained. Historians don’t do this, or at least they shouldn’t.

“Teleologic” comes from the noun “teleology” which has to do in the philosophical sense (as I believe John intended it) with the explanation of phenomena by the purpose they serve rather than by postulated causes. In the theological sense, it refers to the doctrine of design and purpose in the material world.i

Both meanings I find interesting in that, as I mentioned in my last post, I’m preparing a research proposal to study the impact of historian George Bancroft on 19th century historiography. Bancroft has been criticized for his views about America’s destiny being pre-ordained. Frank Freidel captured it well in his work, The Golden Age of American History.

Both meanings I find interesting in that, as I mentioned in my last post, I’m preparing a research proposal to study the impact of historian George Bancroft on 19th century historiography. Bancroft has been criticized for his views about America’s destiny being pre-ordained. Frank Freidel captured it well in his work, The Golden Age of American History.

Bancroft saw a divine shaping of American destinies, from the founding of the individual colonies through the successful culmination of the struggle for independence, and beyond to his own day. He wrote in his preface in 1834, “It is the object of the present work to explain how the change in the condition of our land has been brought about; and, as the fortunes of a nation are not under the control of blind destiny, to follow the steps by which a favoring Providence, calling our institutions into being, has conducted the country to its present happiness and glory.”ii

As the new “scientific history” began to emerge, this position received considerable challenge.

My thanks to both commenter’s for their excellent discussion.

Photo above of Creation of the Sun and Moonby Michelangelo, face detail of God. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

i Oxford Pocket American Dictionary of Current English, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 835.

iiFrank Freidel, The Golden Age of American History [book on-line] (New York: G. Braziller, 1959, accessed 30 December 2007), 70; available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=4419028; Internet.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part IX: The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability