Posts Tagged ‘Avery Craven’

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part IX: The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability

A review of the literature reveals – not surprisingly – a lack of agreement over whether the American Civil War was inevitable. Given the fact that it did occur, the question under consideration might be better stated as “at what point in time” did the American Civil War became unavoidable.

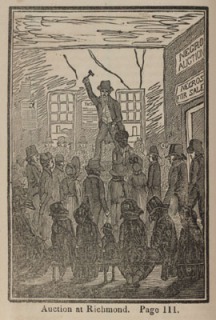

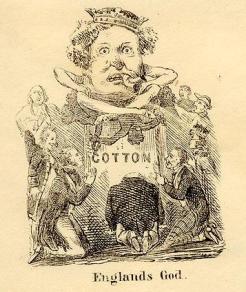

Some would argue that war became predestined at the point when the slave trade was first introduced to the colonies. Others have suggested that civil war became preordained when the founding fathers created a Constitution that professed freedom for all but failed to deal with the country’s practice of chattel slavery (image left of slave auction at Richmond). But portions of the country had demonstrated a willingness to move away slavery. And there was some indication that even slave owners in the south did not expect the practice to go on indefinitely. Certainly the rise of King Cotton, made feasible by the invention of the cotton gin and cotton varieties more suited to the southern climate, slowed the inclination to move away from slavery. Even so, the country had opportunity and demonstrated an ability to find compromise on the issues surrounding slavery time and again and could have

Some would argue that war became predestined at the point when the slave trade was first introduced to the colonies. Others have suggested that civil war became preordained when the founding fathers created a Constitution that professed freedom for all but failed to deal with the country’s practice of chattel slavery (image left of slave auction at Richmond). But portions of the country had demonstrated a willingness to move away slavery. And there was some indication that even slave owners in the south did not expect the practice to go on indefinitely. Certainly the rise of King Cotton, made feasible by the invention of the cotton gin and cotton varieties more suited to the southern climate, slowed the inclination to move away from slavery. Even so, the country had opportunity and demonstrated an ability to find compromise on the issues surrounding slavery time and again and could have  conceivably continued to do so had other factors not pushed the country to war.

conceivably continued to do so had other factors not pushed the country to war.

Sectional differences, well evident even in colonial days, had the potential to make civil war predestined but historian Avery Craven suggests otherwise. “Physical and social differences between North and South did not in themselves necessarily imply an irrepressible conflict. They did not mean that civil war had been decreed from the beginning by Fate.”[i] He points out that the federal system created by the founding fathers had room for differences and that England herself adopted the model of American federalism and used it to manage widely disparate regions.[ii]

Kenneth Stampp in his work, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink, suggests that “…1857 was probably the year when the North and South reached the political point of no return — when it became well nigh impossible to head off a violent resolution of the differences between them.”[iii] Stampp identified three primary factors that catapulted the country toward disunion within that twelve month period.

Kenneth Stampp in his work, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink, suggests that “…1857 was probably the year when the North and South reached the political point of no return — when it became well nigh impossible to head off a violent resolution of the differences between them.”[iii] Stampp identified three primary factors that catapulted the country toward disunion within that twelve month period.

-

The first was the increase in sectional conflict centered on Kansas.

-

The second was President Buchanan’s fall from grace among most of the Northerners who had voted for him after he supported the Lecompton Constitution and thus broke his pre-election promises. This sparked one of the most vicious debates in Congress and led to…

-

the third happening which was the crisis that occurred in the national Democratic Party from which “it did not recover until after the Civil War.”[iv] That schism in the party opened the way for Abraham Lincoln’s candidacy for the presidency which in turn raised sectional tensions between North and South to new heights.

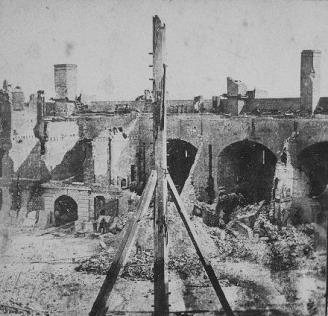

Civil War historiographer Gobar Boritt suggests that the American Civil War only became inevitable after the attack on Fort Sumter (pictured right after surrender) and with this I agree. “The popular uprising, North and South, that followed the fight over Sumter, combined with willing leadership on both sides, made the Civil War inevitable. It was not that before.”[v] Boritt acknowledges that “the probability of war” continued to grow in the 1850s, but that “the country’s fate was not sealed until the ides of April, 1861.”[vi]

Civil War historiographer Gobar Boritt suggests that the American Civil War only became inevitable after the attack on Fort Sumter (pictured right after surrender) and with this I agree. “The popular uprising, North and South, that followed the fight over Sumter, combined with willing leadership on both sides, made the Civil War inevitable. It was not that before.”[v] Boritt acknowledges that “the probability of war” continued to grow in the 1850s, but that “the country’s fate was not sealed until the ides of April, 1861.”[vi]

My conclusion is that the American Civil War was not inevitable but was, rather, the result of a confluence of factors which – taken in aggregate and flared by extremists – resulted in a war unwanted by the majority of Americans. Contributory to the war was the influence of specific individuals – not the least of which was Abraham Lincoln himself. Other politicians, by their action or inaction at critical moments, also had part to play in the circumstances that led to war. Debate over the war’s inevitability has been and will continue to be rigorous.

This post concludes a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes, Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity, Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control, and Part VIII: The Influence of the Individual.

As always, I invite your comments.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

___________________

Photo Credits:

Slave Auction, Richmond, Virginia, 1830. [Source: University of Virginia. Imaged reference: Bourne01. George Bourne, Picture of slavery in the United State of America. . . (Boston, 1838).

Cotton – England’s God [Pictorial envelope] [LOC CALL NUMBER PR-022-3-14-19]

Fort Sumter after evacuation, flagpole shot away twice. [Stereograph], 1861. [LOC CALL NUMBER PR-065-798-22

Endnotes:

[i] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 1.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Stampp, Kenneth M. America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. Vers. [book on-line] Internet. Questia.com.New York: Oxford University Press. 1990. available from questia.com, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?action=openPageViewer&docId=24268497 (accessed September 1, 2007), viii.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] ” ‘And the War Came’? Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 6.

[vi] Ibid.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part VIII: The Influence of the Individual

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes, Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity, and Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control.

___________________

Civil War scholar Gabor Boritt posits a fascinating theory that the impact of an individual can, in fact, be more influential in the determination of history’s direction than the long confluence of time.[i] “…It may be declared with confidence that a giant in the earth, or a crucial moment, weighs more in the scales of history than dreary ages.”[ii] The giant of which he spoke was Abraham Lincoln. His view makes Lincoln a central figure of both American mythology and history. Lincoln’s role in the coming of the Civil War he “divides into four increasingly important stages.”[iii]

Civil War scholar Gabor Boritt posits a fascinating theory that the impact of an individual can, in fact, be more influential in the determination of history’s direction than the long confluence of time.[i] “…It may be declared with confidence that a giant in the earth, or a crucial moment, weighs more in the scales of history than dreary ages.”[ii] The giant of which he spoke was Abraham Lincoln. His view makes Lincoln a central figure of both American mythology and history. Lincoln’s role in the coming of the Civil War he “divides into four increasingly important stages.”[iii]

- First, in the 1850s as tensions grew, Lincoln was one of many political leaders,

familiar mostly in and around Illinois, though as the decade progressed so did his reputation in the North.

- Second, in 1860 he won the presidential nomination of the Republican [P]arty and became a nationally known figure.

- Third, from his election in early November to his inauguration on March 4, 1861, he was the president-elect.

- Fourth, in the White House he presided over events that led to Sumter.

As one stage followed another, Lincoln’s stand changed only gradually, but his voice grew ever more weighty until the end when, together with the voice of President Jefferson Davis, it proved to be decisive.[iv]

I would suggest that there were others whose individual influence – while perhaps not equal to that of Lincoln’s – none the less, impacted the direction of the nation. Key to the South was the “triumvirate of secession” – extremists Robert Rhett, William Yancey, and Edmun Ruffin (pictured below). Each, according to his gifts, kept the pressure for secession constant, the evils of the North apparent. In the period after Lincoln’s election, they leveraged the fear, uncertainty and doubt created by Northern and Southern newspapers to move the populous from defeat to secession as the only alternative left.[v] [See more about Rhett, Yancey and Ruffin in my post “The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War” here.]

They fought delay. Many of the leaders had long believed the Union a curse to the South and they feared that if they moved too deliberately the North might offer favorable terms. Others urged quick action lest the people cool off and accept less than justice. They must strike while the iron was hot. Delay was their worst enemy.

By December 17, 1860, Rhett and his followers had secured a convention in South Carolina, composed of those who were ready to stand alone, if necessary, in defense of Southern rights. The next day an ordinance of secession was adopted. Within six weeks, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had followed South Caroline’s example. The Cotton Kingdom was ready to form itself into the Confederate States of America.[vi]

Is it a wonder that Edmun Ruffin was among the first to fire a cannon on Fort Sumter?

At a nearby battery, another fire-eater was ready. Edmund Ruffin, with his long flowing white hair, another momentary exile from a still reluctant Virginia, sixty seven-year-old honorary Palmetto Guard, was ready. Staring into the dark, knowing where the enemy was, he sent the first shot from a columbaid into the fort flying the unseen flag of the United States.[vii]

Key individuals in the North included those who catapulted the Abolitionist message into the public consciousness. For this reason, John Brown must be included. The men surrounding Lincoln – Seward, Chase, Bates, Douglas and Buchanan – also deserve a chair.

And So What the Cause?

The Civil War can be attributed to no single cause. Slavery was undeniably an influencing factor – a common thread – inexorably tied to the sectional crises that evolved as the country expanded. Profound sectional differences – social, cultural, spiritual, economic, political – provided sufficient tender to ignite into violent conflict – given the spark. The “fanatical edge” and our politicians created the sparks that erupted in violence and pushed the nation over the precipice and into war. Several key individuals tipped the balance. Chief among these were: the Southern fire-eaters Rhett, Yancey and Ruffin, abolitionists who turned up the heat of anti-slavery sentiments in the North, and – pointedly – Abraham Lincoln himself.

For more reading, I highly recommend Gabor S. Boritt’s Why the Civil War Came. His essay titled “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility” is excellent. Avery Craven’s The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. provides very interesting commentary on Rhett, Yancey, and Ruffin (and more about their individual strengths) and a wealth of information on Antebellum America and its march toward war.

In the next post, I’ll tackle the second question of the series: The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

_______________________

[i] “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 7., [ii] Ibid., [iii] Ibid., [iv] Ibid.

[v] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 19 57), 433., [vi] Ibid.

57), 433., [vi] Ibid.

[vii] Boritt, “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 5.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, and Part IV: The Antebellum North.

___________________

Sectional disputes rose and ebbed numerous times in the years before the war. Modernization created social tensions ![]() because, as pointed out by James McPherson, “not all groups in American society participated equally in the modernizing process or accepted the values that promoted it. The most important dissenters were found in the South.”[i] The South’s failure to modernize was perceived by many of her citizens as actually desirable.

because, as pointed out by James McPherson, “not all groups in American society participated equally in the modernizing process or accepted the values that promoted it. The most important dissenters were found in the South.”[i] The South’s failure to modernize was perceived by many of her citizens as actually desirable.

Sectional arguments expanded to include topics like internal improvements, tariffs, and whether expansion west and south would upset the parity between free and slave states. Foundational to the latter was the belief on the part of the slaveholder in their right to a slave-based social order and a need for assurances of its continuity. Equal representation in government was perceived as critical to that goal.

The rise of abolitionism – largely in the North – put the proponents of slavery on the defensive. The formation of the American Anti-Slavery Society marked the beginning of militant abolitionism and an unprecedented crusade that would rival any modern national marketing campaign. Barbed attacks against slaveholding southerners were launched. They were called the great enemies of democracy and flagrant sinners.[ii] The anti-slavery crusade thus became both a moral one and imperative for the preservation of democracy. Abolitionists created in a section’s consciousness the belief in a “Slave Power.”[iii] Historian Avery Craven suggests that when politicians successfully linked expansion and slavery, the Christian masses accepted as de facto the Abolition attitudes toward both the South and slavery.[iv] Civil war, he contends, “was then in the making.”[v]

The pro-slavery faction fought back with their own “sweeping ideological counterattack that took the form of an assertion that slavery, far from being a necessary evil, was in fact a ‘positive good.’”[vi] “The section developed a siege mentality; unity in the face of external attack and vigilance against the internal threat of slave insurrections became mandatory.”[vii] To insulate itself from the influence of the anti-slavery North, some in the South called for its citizens to shun Northern magazines and books and refrain from sending young men to northern colleges.

The pro-slavery faction fought back with their own “sweeping ideological counterattack that took the form of an assertion that slavery, far from being a necessary evil, was in fact a ‘positive good.’”[vi] “The section developed a siege mentality; unity in the face of external attack and vigilance against the internal threat of slave insurrections became mandatory.”[vii] To insulate itself from the influence of the anti-slavery North, some in the South called for its citizens to shun Northern magazines and books and refrain from sending young men to northern colleges.

The debate over slavery thus infiltrated politics, economics, religion and social policy. Not surprisingly, those who felt most threatened began to speak more loudly of secession.

Next post: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity

© 2007 Rene Tyree

Images:

Library of Congress: The African-American Mosaic.

“Declaration of the Anti-Slavery Convention Assembled in Philadelphia, December 4, 1833” R[ueben] S. Gilbert, Illustrator Philadelphia: Merrihew & Gunn, 1833 Broadside Rare Book and Special Collections Division

“Anthony Burns” Boston: R.M. Edwards, 1855 Broadside Prints and Photographs Division

____________________

[i] James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 22.

[ii] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 150.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 51-52.

[vii] Ibid., 52.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part III – The Antebellum South

The Southern man aspired to a lifestyle that had, as utopian model of success, the English country farmer. Jeffersonian agrarianism was valued over Hamiltonian industrialization.

To achieve success, cheap labor in the form of slavery was embraced. The capital of the south was invested in slaves even after modernized farming equipment became available. More land was needed to produce more crops which required, in turn, more slaves. This cycle repeated until some 4 million slaves populated the South by mid-century. The system became self-perpetuating because – as posited by historian James McPherson – slavery undermined the work-ethic of both slave and Southern whites. The slave obviously had limited opportunity for advancement. Manual labor became associated with bondage and so lacked honor. The result was a limited flow of white immigrants to the south who could provide an alternative labor force and an increase in the migration of southern whites to free states.[i]

became associated with bondage and so lacked honor. The result was a limited flow of white immigrants to the south who could provide an alternative labor force and an increase in the migration of southern whites to free states.[i]

Simply stated, the South chose not to modernize. It hosted little manufacturing. It also lacked a well developed transportation system (a fact that would prove key to the conduct of the war).

White supremacy was simply a fact. Part of the responsibility of owning slaves was to care for their material needs as you would children. White southern children grew up with a facility for “command” and became a part of what was viewed by many as a southern aristocracy.[ii]

According to historian Avery Craven, “three great forces always worked toward a common Southern pattern. They were:

- a rural way of life capped by an English gentleman ideal,

- a climate in part more mellow than other sections enjoyed, and

- the presence of the Negro race in quantity. More than any other forces these things made the South Southern.”[iii]

Next post – The Antebellum North

For additional reading…

On Jeffersononian Agrarianism see the University of Virginia site here.

[i] James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 10., 41.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 33.

Photo Credits:

Watercolor View of the West Front of Monticello and Garden (1825) by Jane Braddick. Peticolas. The children are Thomas Jefferson’s grandchildren. Public Domain [Source: Wikipedia Commons]

Inspection and Sale of a Slave. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Digital ID: cph 3a17639 Source: b&w film copy neg.

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-15392 (b&w film copy neg.)

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA