Posts Tagged ‘Gabor Boritt’

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part IX: The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability

A review of the literature reveals – not surprisingly – a lack of agreement over whether the American Civil War was inevitable. Given the fact that it did occur, the question under consideration might be better stated as “at what point in time” did the American Civil War became unavoidable.

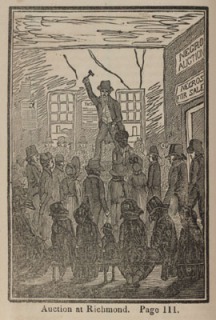

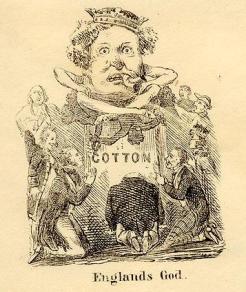

Some would argue that war became predestined at the point when the slave trade was first introduced to the colonies. Others have suggested that civil war became preordained when the founding fathers created a Constitution that professed freedom for all but failed to deal with the country’s practice of chattel slavery (image left of slave auction at Richmond). But portions of the country had demonstrated a willingness to move away slavery. And there was some indication that even slave owners in the south did not expect the practice to go on indefinitely. Certainly the rise of King Cotton, made feasible by the invention of the cotton gin and cotton varieties more suited to the southern climate, slowed the inclination to move away from slavery. Even so, the country had opportunity and demonstrated an ability to find compromise on the issues surrounding slavery time and again and could have

Some would argue that war became predestined at the point when the slave trade was first introduced to the colonies. Others have suggested that civil war became preordained when the founding fathers created a Constitution that professed freedom for all but failed to deal with the country’s practice of chattel slavery (image left of slave auction at Richmond). But portions of the country had demonstrated a willingness to move away slavery. And there was some indication that even slave owners in the south did not expect the practice to go on indefinitely. Certainly the rise of King Cotton, made feasible by the invention of the cotton gin and cotton varieties more suited to the southern climate, slowed the inclination to move away from slavery. Even so, the country had opportunity and demonstrated an ability to find compromise on the issues surrounding slavery time and again and could have  conceivably continued to do so had other factors not pushed the country to war.

conceivably continued to do so had other factors not pushed the country to war.

Sectional differences, well evident even in colonial days, had the potential to make civil war predestined but historian Avery Craven suggests otherwise. “Physical and social differences between North and South did not in themselves necessarily imply an irrepressible conflict. They did not mean that civil war had been decreed from the beginning by Fate.”[i] He points out that the federal system created by the founding fathers had room for differences and that England herself adopted the model of American federalism and used it to manage widely disparate regions.[ii]

Kenneth Stampp in his work, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink, suggests that “…1857 was probably the year when the North and South reached the political point of no return — when it became well nigh impossible to head off a violent resolution of the differences between them.”[iii] Stampp identified three primary factors that catapulted the country toward disunion within that twelve month period.

Kenneth Stampp in his work, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink, suggests that “…1857 was probably the year when the North and South reached the political point of no return — when it became well nigh impossible to head off a violent resolution of the differences between them.”[iii] Stampp identified three primary factors that catapulted the country toward disunion within that twelve month period.

-

The first was the increase in sectional conflict centered on Kansas.

-

The second was President Buchanan’s fall from grace among most of the Northerners who had voted for him after he supported the Lecompton Constitution and thus broke his pre-election promises. This sparked one of the most vicious debates in Congress and led to…

-

the third happening which was the crisis that occurred in the national Democratic Party from which “it did not recover until after the Civil War.”[iv] That schism in the party opened the way for Abraham Lincoln’s candidacy for the presidency which in turn raised sectional tensions between North and South to new heights.

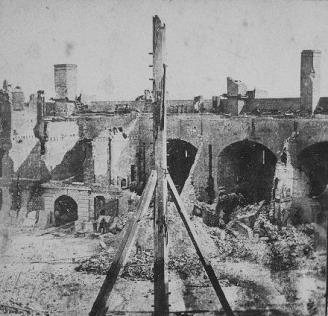

Civil War historiographer Gobar Boritt suggests that the American Civil War only became inevitable after the attack on Fort Sumter (pictured right after surrender) and with this I agree. “The popular uprising, North and South, that followed the fight over Sumter, combined with willing leadership on both sides, made the Civil War inevitable. It was not that before.”[v] Boritt acknowledges that “the probability of war” continued to grow in the 1850s, but that “the country’s fate was not sealed until the ides of April, 1861.”[vi]

Civil War historiographer Gobar Boritt suggests that the American Civil War only became inevitable after the attack on Fort Sumter (pictured right after surrender) and with this I agree. “The popular uprising, North and South, that followed the fight over Sumter, combined with willing leadership on both sides, made the Civil War inevitable. It was not that before.”[v] Boritt acknowledges that “the probability of war” continued to grow in the 1850s, but that “the country’s fate was not sealed until the ides of April, 1861.”[vi]

My conclusion is that the American Civil War was not inevitable but was, rather, the result of a confluence of factors which – taken in aggregate and flared by extremists – resulted in a war unwanted by the majority of Americans. Contributory to the war was the influence of specific individuals – not the least of which was Abraham Lincoln himself. Other politicians, by their action or inaction at critical moments, also had part to play in the circumstances that led to war. Debate over the war’s inevitability has been and will continue to be rigorous.

This post concludes a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes, Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity, Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control, and Part VIII: The Influence of the Individual.

As always, I invite your comments.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

___________________

Photo Credits:

Slave Auction, Richmond, Virginia, 1830. [Source: University of Virginia. Imaged reference: Bourne01. George Bourne, Picture of slavery in the United State of America. . . (Boston, 1838).

Cotton – England’s God [Pictorial envelope] [LOC CALL NUMBER PR-022-3-14-19]

Fort Sumter after evacuation, flagpole shot away twice. [Stereograph], 1861. [LOC CALL NUMBER PR-065-798-22

Endnotes:

[i] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 1.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Stampp, Kenneth M. America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. Vers. [book on-line] Internet. Questia.com.New York: Oxford University Press. 1990. available from questia.com, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?action=openPageViewer&docId=24268497 (accessed September 1, 2007), viii.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] ” ‘And the War Came’? Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 6.

[vi] Ibid.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part VIII: The Influence of the Individual

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes, Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity, and Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control.

___________________

Civil War scholar Gabor Boritt posits a fascinating theory that the impact of an individual can, in fact, be more influential in the determination of history’s direction than the long confluence of time.[i] “…It may be declared with confidence that a giant in the earth, or a crucial moment, weighs more in the scales of history than dreary ages.”[ii] The giant of which he spoke was Abraham Lincoln. His view makes Lincoln a central figure of both American mythology and history. Lincoln’s role in the coming of the Civil War he “divides into four increasingly important stages.”[iii]

Civil War scholar Gabor Boritt posits a fascinating theory that the impact of an individual can, in fact, be more influential in the determination of history’s direction than the long confluence of time.[i] “…It may be declared with confidence that a giant in the earth, or a crucial moment, weighs more in the scales of history than dreary ages.”[ii] The giant of which he spoke was Abraham Lincoln. His view makes Lincoln a central figure of both American mythology and history. Lincoln’s role in the coming of the Civil War he “divides into four increasingly important stages.”[iii]

- First, in the 1850s as tensions grew, Lincoln was one of many political leaders,

familiar mostly in and around Illinois, though as the decade progressed so did his reputation in the North.

- Second, in 1860 he won the presidential nomination of the Republican [P]arty and became a nationally known figure.

- Third, from his election in early November to his inauguration on March 4, 1861, he was the president-elect.

- Fourth, in the White House he presided over events that led to Sumter.

As one stage followed another, Lincoln’s stand changed only gradually, but his voice grew ever more weighty until the end when, together with the voice of President Jefferson Davis, it proved to be decisive.[iv]

I would suggest that there were others whose individual influence – while perhaps not equal to that of Lincoln’s – none the less, impacted the direction of the nation. Key to the South was the “triumvirate of secession” – extremists Robert Rhett, William Yancey, and Edmun Ruffin (pictured below). Each, according to his gifts, kept the pressure for secession constant, the evils of the North apparent. In the period after Lincoln’s election, they leveraged the fear, uncertainty and doubt created by Northern and Southern newspapers to move the populous from defeat to secession as the only alternative left.[v] [See more about Rhett, Yancey and Ruffin in my post “The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War” here.]

They fought delay. Many of the leaders had long believed the Union a curse to the South and they feared that if they moved too deliberately the North might offer favorable terms. Others urged quick action lest the people cool off and accept less than justice. They must strike while the iron was hot. Delay was their worst enemy.

By December 17, 1860, Rhett and his followers had secured a convention in South Carolina, composed of those who were ready to stand alone, if necessary, in defense of Southern rights. The next day an ordinance of secession was adopted. Within six weeks, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had followed South Caroline’s example. The Cotton Kingdom was ready to form itself into the Confederate States of America.[vi]

Is it a wonder that Edmun Ruffin was among the first to fire a cannon on Fort Sumter?

At a nearby battery, another fire-eater was ready. Edmund Ruffin, with his long flowing white hair, another momentary exile from a still reluctant Virginia, sixty seven-year-old honorary Palmetto Guard, was ready. Staring into the dark, knowing where the enemy was, he sent the first shot from a columbaid into the fort flying the unseen flag of the United States.[vii]

Key individuals in the North included those who catapulted the Abolitionist message into the public consciousness. For this reason, John Brown must be included. The men surrounding Lincoln – Seward, Chase, Bates, Douglas and Buchanan – also deserve a chair.

And So What the Cause?

The Civil War can be attributed to no single cause. Slavery was undeniably an influencing factor – a common thread – inexorably tied to the sectional crises that evolved as the country expanded. Profound sectional differences – social, cultural, spiritual, economic, political – provided sufficient tender to ignite into violent conflict – given the spark. The “fanatical edge” and our politicians created the sparks that erupted in violence and pushed the nation over the precipice and into war. Several key individuals tipped the balance. Chief among these were: the Southern fire-eaters Rhett, Yancey and Ruffin, abolitionists who turned up the heat of anti-slavery sentiments in the North, and – pointedly – Abraham Lincoln himself.

For more reading, I highly recommend Gabor S. Boritt’s Why the Civil War Came. His essay titled “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility” is excellent. Avery Craven’s The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. provides very interesting commentary on Rhett, Yancey, and Ruffin (and more about their individual strengths) and a wealth of information on Antebellum America and its march toward war.

In the next post, I’ll tackle the second question of the series: The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

_______________________

[i] “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 7., [ii] Ibid., [iii] Ibid., [iv] Ibid.

[v] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 19 57), 433., [vi] Ibid.

57), 433., [vi] Ibid.

[vii] Boritt, “Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 5.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control

This post continues a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes and Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity.

___________________

Political discord represents yet another candidate for the war’s cause. Late historian William E. Gienapp (pictured right) suggests that “however much social and economic developments fueled the sectional conflict, the coming of the Civil War must be explained ultimately in political terms, for the outbreak of war in April 1861 represented the complete breakdown of the American political system. As such, the Civil War constituted the greatest single failure of American democracy.”[i]

Political discord represents yet another candidate for the war’s cause. Late historian William E. Gienapp (pictured right) suggests that “however much social and economic developments fueled the sectional conflict, the coming of the Civil War must be explained ultimately in political terms, for the outbreak of war in April 1861 represented the complete breakdown of the American political system. As such, the Civil War constituted the greatest single failure of American democracy.”[i]

Gienapp poin ts to the role of slavery as the underlying cause of the sectional conflict. “Without slavery it is impossible to imagine a war between the North and the South (or indeed, the existence of anything we would call “the South” except as a geographic region).”[ii] He also asserts that America’s slave heritage was completely associated with race. That is, had the slaves brought to America been white, the practice would have disappeared much earlier.[iii] But an argument asserting slavery as chief cause of the war neglects the fact that not only was it older than the republic, but “for over half a century following adoption of the Constitution, the institution had only sporadically been an issue in national politics, and it had never dominated state politics in either section.”[iv] What changed? It was the rise of the slavery issue in American society; that is, the heightened awareness of it. This development was rooted in a number of changes in American society in the first half of the nineteenth century already addressed.[v]

ts to the role of slavery as the underlying cause of the sectional conflict. “Without slavery it is impossible to imagine a war between the North and the South (or indeed, the existence of anything we would call “the South” except as a geographic region).”[ii] He also asserts that America’s slave heritage was completely associated with race. That is, had the slaves brought to America been white, the practice would have disappeared much earlier.[iii] But an argument asserting slavery as chief cause of the war neglects the fact that not only was it older than the republic, but “for over half a century following adoption of the Constitution, the institution had only sporadically been an issue in national politics, and it had never dominated state politics in either section.”[iv] What changed? It was the rise of the slavery issue in American society; that is, the heightened awareness of it. This development was rooted in a number of changes in American society in the first half of the nineteenth century already addressed.[v]

As mentioned in previous posts in this series, the abolitionist movement did a great deal to raise that awareness. But Gienapp suggests that “it was the politicians themselves, as part of the struggle for control of the two major parties, wh o ultimately injected the slavery issue into national politics.”[vi] The key development was the introduction in Congress in 1846 of the Wilmot Proviso, which prohibited slavery from any territory acquired from Mexico, by a group of Van Burenite Democrats who were angry with President James K. Polk (pictured right) and his southern advisers. Once the slavery issue, in the shape of the question of its expansion into the western territories, entered the political arena, it proved impossible to get it out. The issue took on a life of its own, and when politicians tried to drop the issue after 1850, they discovered that many voters were unwilling to acquiesce.[vii]

o ultimately injected the slavery issue into national politics.”[vi] The key development was the introduction in Congress in 1846 of the Wilmot Proviso, which prohibited slavery from any territory acquired from Mexico, by a group of Van Burenite Democrats who were angry with President James K. Polk (pictured right) and his southern advisers. Once the slavery issue, in the shape of the question of its expansion into the western territories, entered the political arena, it proved impossible to get it out. The issue took on a life of its own, and when politicians tried to drop the issue after 1850, they discovered that many voters were unwilling to acquiesce.[vii]

Gienapp makes a good case for the war’s true cause in the following discourse.

A second critical development, intimately related to the first, was the crystallization of rival sectional ideologies oriented toward protecting white equality and opportunity. Increasingly, each section came to see the other section and its institutions as a threat to its vital social, political, and economic interests. Increasingly, each came to think that one section or the other had to be dominant. Informed by these ideologies, a majority of the residents of each section feared the other, and well before the fighting started the sectional conflict represented a struggle for control of the nation’s future.

It fell to the political system to adjudicate differences between the sections and preserve a feeling of mutual cooperation and unity. And for a long time the political system had successfully defused sectional tensions. Because it brought northern and southern leaders together, Congress was the primary arena for hammering out solutions to sectional problems. In various sectional confrontations–the struggle over the admissi

on of Missouri as a slave state in 1819-21, the controversy over nullification and the tariff in 1833, the problem of the status of slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico in 1850, and the struggle over the proslavery Lecompton constitution in 1858-Congress had always managed to find some acceptable way out of the crisis.

Yet the American political system was particularly vulnerable to sectional strains and tensions. One reason was the institutional structure of American politics. The Civil War occurred within a particular political institutional framework that, while it did not make the war inevitable, was essential to the coming of the war.

Integral to this institutional framework was the United States Constitution. While some aspects of the Constitution retarded the development of sectionalism, it contained a number of provisions that strengthened the forces of sectional division in the nation. No constitution can anticipate all future developments and conclusively deal with all controversies that subsequently arise. The purpose in analyzing the Constitution’s role in the sectional conflict is not to fault its drafters or condemn it as a flawed document, but rather to indicate the importance of certain of its clauses for the origins of the war.

One signifi

cant feature of the Constitution was its provision for amendment. Lurking beneath the surface in the slavery controversy was white Southerners’ fear that the Constitution would be amended to interfere with the institution. In advocating secession after Abraham Lincoln’s election, Governor Andrew B. Moore of Alabama (pictured above) predicted that the Republicans would quickly create a number of new free states in the West, which “in hot haste will be admitted to the Union, until they have a majority to alter the Constitution. Then slavery will be abolished by law in the States.”[viii]

The fear, uncertainty and doubt associated with this possibility, on the part of the Southern political establishment, pushed the country toward war.

The next post: “The Influence of the Individual.”

For further reading, I recommend The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War by Michael F. Holt and Why the Civil War Came, edited by Gabor S. Boritt.

© 2007 Rene Tyree

_________________________

Photo credits:

Historian William E. Gienapp. Source: Harvard Gazette Archives, Issue: April 07, 2005.

Poster Announcing Sale and Rental of Slaves, Saint Helena (South Atlantic), 1829. Source: The Atlantic Slave Trade and

Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record., Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr., The Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Image H003.

President James K. Polk

Cropped image of the constitution of Kansas

Governor Andrew B. Moore of Alabama. Source: Alabama Department of Archive and History

[i] William E. Gienapp, “The Crisis of American Democracy, the Political System and the Coming of the Civil War,” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt [book on-line] (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, accessed 1 September 2007), 82; available from questia.com http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=78779127; Internet., [ii] Ibid., [iii] Ibid., [iv] Ibid., [v] Ibid., [vi] Ibid., 83., [vii] Ibid., [viii] Ibid., 86.