Posts Tagged ‘Fort Sumter’

Lincoln’s Impact on Military Operations

Bombardment of Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor, a color lithograph by Currier & Ives; (SCALA/Art Resource)

In class, we’ve been discussing how the decisions of the two commanders-in-chief during the American Civil War impacted events at the operational level. Modern scholars have challenged the notion that Lincoln simply stayed involved in military details until he found the right general (Grant). Eliot Cohen posits that’s “Lincoln exercised a constant oversight of the war effort from beginning to end.”(1) This intense interest in providing direction can be seen as early as the events surrounding the attack on Fort Sumter. Lincoln’s order of the nonviolent resupply of the fort, which caused the Confederates to fire the first shot and thus initiate the war, demonstrates Lincoln’s willingness to go against the advice of senior commanders. Equally important, it showed his considerable ability at playing the game of strategy. Cohen summed it up well by calling Lincoln’s move “characteristically cunning” and revealing of “a steely willingness to accept the hazards of war.”(2)

Lincoln continued to immerse himself in operational details, stepping back only to a degree when General Grant became General-in-chief but certainly not completely. Lincoln carefully reviewed dispatches and, as has been well documented, literally camped in the telegraph office during battles. In fact, he qualified as a micro-manager to some degree. As such, one of the ways in which his leadership impacted operation was by his dismissal of generals who didn’t perform. “By comparison with our recent presidents, Lincoln was an exceptionally unforgiving boss.”(3) He also took considerable personal interest in the technological advancements that took place prior to and during the war. His personal influence could make things happen as it did with the development of river canon, which helped to win control by the Union of the Mississippi River and southern ports.

Lincoln was so intent upon staying informed of field activities that he installed journalist Charles Dana as, effectively, a spy in Grant’s camp while he was assigned in the west. Dana, who even had his own cipher for sending reports back to Stanton, was also dispatched to observe and report back on the command abilities of General Rosecrans. Lincoln put Dana back in Grant’s camp later in the war even after Grant had demonstrated success and earned Lincoln’s trust. This fact further dispels the notion that Lincoln simply turned over the war’s higher direction to Grant.(4) In fact, Cohen posits that “Lincoln did not merely find his generals; he controlled them. He molded the war to its last days, and he intended to dominate the making of peace at its end.” (5)

(1) Eliot A. Cohen, Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen and Leadership in Wartime, (London: Free Press, 2002), 19.

(2) Ibid., 20.

(3) Ibid., 24.

(4) Ibid., 51.

(5) Ibid., 21.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part IX: The Debate Over the War’s Inevitability

A review of the literature reveals – not surprisingly – a lack of agreement over whether the American Civil War was inevitable. Given the fact that it did occur, the question under consideration might be better stated as “at what point in time” did the American Civil War became unavoidable.

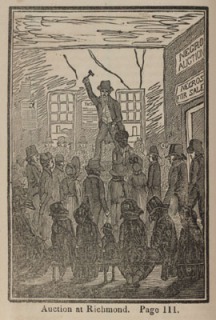

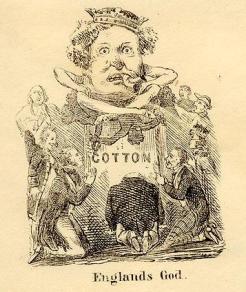

Some would argue that war became predestined at the point when the slave trade was first introduced to the colonies. Others have suggested that civil war became preordained when the founding fathers created a Constitution that professed freedom for all but failed to deal with the country’s practice of chattel slavery (image left of slave auction at Richmond). But portions of the country had demonstrated a willingness to move away slavery. And there was some indication that even slave owners in the south did not expect the practice to go on indefinitely. Certainly the rise of King Cotton, made feasible by the invention of the cotton gin and cotton varieties more suited to the southern climate, slowed the inclination to move away from slavery. Even so, the country had opportunity and demonstrated an ability to find compromise on the issues surrounding slavery time and again and could have

Some would argue that war became predestined at the point when the slave trade was first introduced to the colonies. Others have suggested that civil war became preordained when the founding fathers created a Constitution that professed freedom for all but failed to deal with the country’s practice of chattel slavery (image left of slave auction at Richmond). But portions of the country had demonstrated a willingness to move away slavery. And there was some indication that even slave owners in the south did not expect the practice to go on indefinitely. Certainly the rise of King Cotton, made feasible by the invention of the cotton gin and cotton varieties more suited to the southern climate, slowed the inclination to move away from slavery. Even so, the country had opportunity and demonstrated an ability to find compromise on the issues surrounding slavery time and again and could have  conceivably continued to do so had other factors not pushed the country to war.

conceivably continued to do so had other factors not pushed the country to war.

Sectional differences, well evident even in colonial days, had the potential to make civil war predestined but historian Avery Craven suggests otherwise. “Physical and social differences between North and South did not in themselves necessarily imply an irrepressible conflict. They did not mean that civil war had been decreed from the beginning by Fate.”[i] He points out that the federal system created by the founding fathers had room for differences and that England herself adopted the model of American federalism and used it to manage widely disparate regions.[ii]

Kenneth Stampp in his work, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink, suggests that “…1857 was probably the year when the North and South reached the political point of no return — when it became well nigh impossible to head off a violent resolution of the differences between them.”[iii] Stampp identified three primary factors that catapulted the country toward disunion within that twelve month period.

Kenneth Stampp in his work, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink, suggests that “…1857 was probably the year when the North and South reached the political point of no return — when it became well nigh impossible to head off a violent resolution of the differences between them.”[iii] Stampp identified three primary factors that catapulted the country toward disunion within that twelve month period.

-

The first was the increase in sectional conflict centered on Kansas.

-

The second was President Buchanan’s fall from grace among most of the Northerners who had voted for him after he supported the Lecompton Constitution and thus broke his pre-election promises. This sparked one of the most vicious debates in Congress and led to…

-

the third happening which was the crisis that occurred in the national Democratic Party from which “it did not recover until after the Civil War.”[iv] That schism in the party opened the way for Abraham Lincoln’s candidacy for the presidency which in turn raised sectional tensions between North and South to new heights.

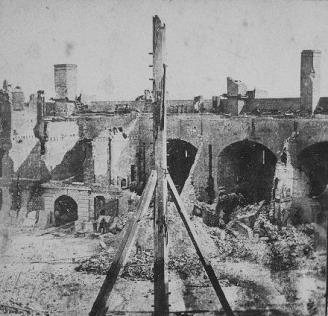

Civil War historiographer Gobar Boritt suggests that the American Civil War only became inevitable after the attack on Fort Sumter (pictured right after surrender) and with this I agree. “The popular uprising, North and South, that followed the fight over Sumter, combined with willing leadership on both sides, made the Civil War inevitable. It was not that before.”[v] Boritt acknowledges that “the probability of war” continued to grow in the 1850s, but that “the country’s fate was not sealed until the ides of April, 1861.”[vi]

Civil War historiographer Gobar Boritt suggests that the American Civil War only became inevitable after the attack on Fort Sumter (pictured right after surrender) and with this I agree. “The popular uprising, North and South, that followed the fight over Sumter, combined with willing leadership on both sides, made the Civil War inevitable. It was not that before.”[v] Boritt acknowledges that “the probability of war” continued to grow in the 1850s, but that “the country’s fate was not sealed until the ides of April, 1861.”[vi]

My conclusion is that the American Civil War was not inevitable but was, rather, the result of a confluence of factors which – taken in aggregate and flared by extremists – resulted in a war unwanted by the majority of Americans. Contributory to the war was the influence of specific individuals – not the least of which was Abraham Lincoln himself. Other politicians, by their action or inaction at critical moments, also had part to play in the circumstances that led to war. Debate over the war’s inevitability has been and will continue to be rigorous.

This post concludes a series on Exploring Causes of the Civil War. Other posts can be read by clicking on any of the following links: Part I: Introduction, Part II: Antebellum America, Part III: The Antebellum South, Part IV: The Antebellum North, Part V: The Rise of Sectional Disputes, Part VI: The Contribution of Constitutional Ambiguity, Part VII: Political Discord, Slavery, and the Fight for Political Control, and Part VIII: The Influence of the Individual.

As always, I invite your comments.

© 2007 L. Rene Tyree

___________________

Photo Credits:

Slave Auction, Richmond, Virginia, 1830. [Source: University of Virginia. Imaged reference: Bourne01. George Bourne, Picture of slavery in the United State of America. . . (Boston, 1838).

Cotton – England’s God [Pictorial envelope] [LOC CALL NUMBER PR-022-3-14-19]

Fort Sumter after evacuation, flagpole shot away twice. [Stereograph], 1861. [LOC CALL NUMBER PR-065-798-22

Endnotes:

[i] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 1.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Stampp, Kenneth M. America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. Vers. [book on-line] Internet. Questia.com.New York: Oxford University Press. 1990. available from questia.com, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?action=openPageViewer&docId=24268497 (accessed September 1, 2007), viii.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] ” ‘And the War Came’? Abraham Lincoln and the Question of Individual Responsibility” in Why the Civil War Came., ed. Gabor S. Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 6.

[vi] Ibid.