Archive for the ‘Library of Congress’ Category

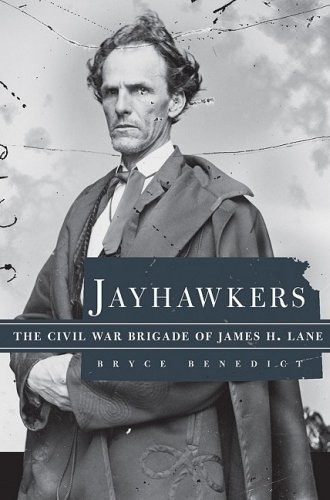

Jayhawkers: The Civil War Brigade of James Henry Lane

ISBN: 978-0-8061-3999-9

Cloth

352 pages

12 b&w illus., 1 map

Published: 2009-04-30

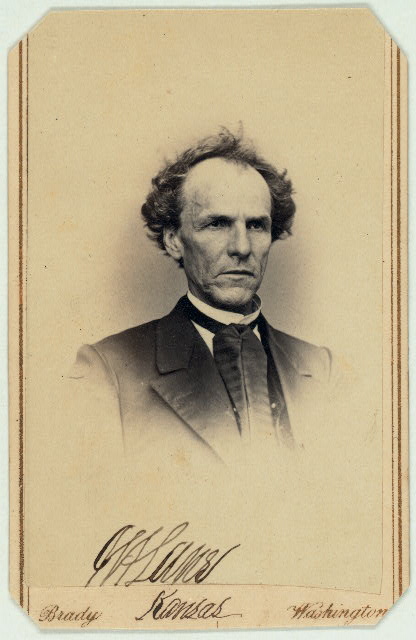

Carte d' visite of James Henry Lane, 1814-1866 Photographer: Brady National Photographic Art Gallery (Washington, D.C.) Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-MSS-44297-33-037 (b&w negative)

The good folks at the University of Oklahoma Press sent me a review copy yesterday of Bryce Benedict’s Jayhawkers: The Civil War Brigade of James Henry Lane. In my usual fashion, I’m posting a few comments prior to a thorough reading.

I live on the borders of Missouri and Kansas so confess some considerable fascination with both Jim Lane and the evolution of war in the towns and farmlands of this part of the Western theater. Lane, a Kansas senator and strong advocate of Lincoln, was a player. Benedict identifies Lincoln himself as having given Lane authority “to raise and command two volunteer regiments.” Lane used them to harass Missourians with violence, theft, and destruction of property in a manner foreshadowing that of Sherman. Benedict posits that Lane thus embraced the notion of “total war” as a means of disabling the enemy’s war machine before it became more widely adopted as a strategy of the Union.

The photo of Lane on the cover (above) was a brilliant choice. After perusing the Library of Congress and finding his carte d’visite (left), it becomes clear that the look of the man fit his personality. In the words of Milton W. Reynolds, Lane was “weird, mysterious, partially insane, partially inspired, and poetic.” He described him as having lived a “…wayward, fitful life of passion and strife, of storm and sunshine a mysterious existence that now dwelt on the mountain-tops of expectation and the very summit of highest realization, and anon in the valley of despondency and deepest gloom.” [1] Lane committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth with a pistol in 1866.

Author Bryce Benedict has produced a well researched work with notes for each chapter and three appendices including considerable information about fate of the casualties of Lane’s brigade, most of whom died from disease.

—–

For further reading, check out these books digitized for online reading at the Library of Congress.

[1] Connelley, William Elsey, (1855-1930) James Henry Lane, the “Grim chieftain” of Kansas (Topeka: Crane, 1899). The Library of Congress Digitized Book. LOC Call number: 9594581, Digitizing sponsor: Sloan Foundation

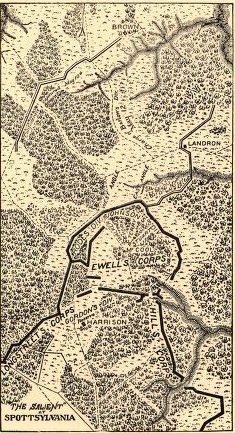

Military History Word of the Day – Salient

salient ˈsālyənt; -lēənt n.

1. a piece of land or section of fortification that juts out to form an angle.

2. an outward bulge in a line of military attack or defense. (see example below)

The word “salient” is used frequently in John F. Schmutz’s The Battle of the Crater: A Complete History (see post on his book here).

Due to the extremely close proximity of the opposing lines between the two forts, sniper fire was heavy and constant in this area. Potter’s division was located in the ravine a little more than one hundred yards from Elliott’s Salient, which itself was situated at an angle in the Rebel line of works, the closest at any part to the Union lines. Observers at the time felt the Union line had penetrated into the interior of the Confederates’ lines in this area after the last battle and was thus occupying a tenuous position. (2)

The National Park Service identifies Elliott’s Salient as a point where Federals and Confederates had come close together.

One of these locations was in front of Elliott’s Salient, a Confederate strong point near Cemetery Hill and old Blandford Church. Here the Confederate position and the Union picket line were less than 400 feet apart. Because of the proximity of the Union line, Elliott’s Salient was well fortified. Behind earthen embankments was a battery of four guns, and two veteran South Carolina infantry regiments were stationed on either side. Behind these were other defensive works; before them the ground sloped gently downward toward the Union advance line. (3)

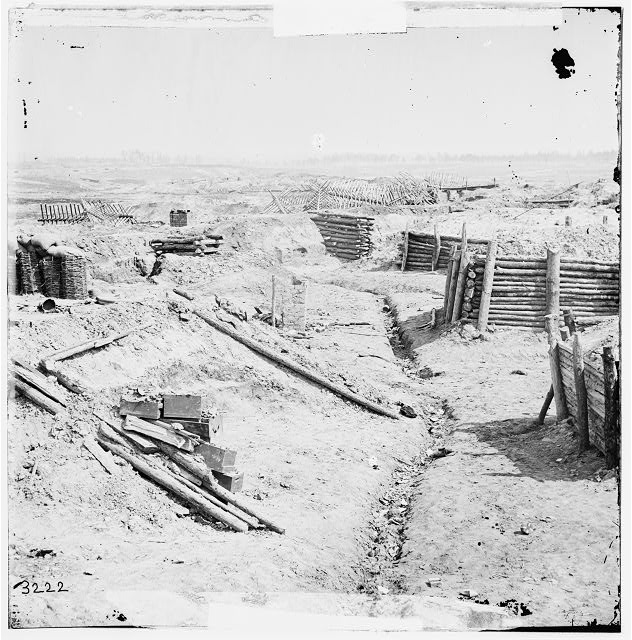

![Gracie's Salient Petersburg Petersburg, Virginia. Confederate fortifications at "Gracie's Salient." LOC Call #: LC-B815- 1059[P&P]](https://wigwags.files.wordpress.com/2009/08/gracies-salient-petersburg.jpg?w=700)

Petersburg, Virginia. Confederate fortifications at "Gracie's Salient." Courtesy of the Library of Congress LC-B815- 1059

Other well known military salients:

From the National Park Service’s virtual tour of the Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania Battlefields: By mid-afternoon on May 12 the fighting at the Muleshoe Salient had reached an impasse. By coincidence, both sides focused attention on another bulge in the Confederate lines known as Heth’s Salient. General Grant ordered General Ambrose Burnside to attack Heth’s Salient at the same time as General Lee ordered General Jubal Early to attack Burnside’s left flank. In doing so, he hoped to relieve pressure on the Confederates at the Bloody Angle.

Muleshoe Salient: Look for reference to Mule Shoe Salient in the Wikipedia post here.

From the National Park Services (see the full story here): The armies flowed onto the battlefield the rest of the day, extending corresponding lines of earthworks east and west of the Brock Road. Ewell’s corps filed in on Anderson’s right and built their entrenchments in the dark to conform with elevated terrain along their front. First light revealed that Ewell’s soldiers had concocted a huge salient, or bulge, in the Confederate line, pointing north in the direction of the Federals. The men called it the “Mule Shoe” because of its shape, but Southern engineers called it trouble. Salient’s could be attacked not only in front but from both sides, and as a rule officers liked to avoid them. Lee, however, opted to retain the position trusting that his cannoneers could keep the “Mule Shoe” safe enough.

From the National Park Service (see the full story here): On May 10, the Union found a weakness in the Confederate defenses. Colonel Emory Upton was ordered with 5,000 men to attack a slight bulge in the Confederate lines known as Doles’s Salient. Upton’s men approached the Confederates on a narrow road (typical of the roads in the area that linked one farm with another) through the woods.

Ypres Salient: Famous for the World War I battle that took place there.

(1) “salient.” The Oxford Essential Dictionary of the U.S. Military. 2001. Encyclopedia.com. (August 23, 2009). http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O63-salient.html

(2) John F. Schmutz, The Battle of the Crater: A Complete History, (Jefferson, North Carolina: 2009), 50.

(3) “The Battle of the Crater, July 30, 1864,” http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/hh/13/hh13f.htm

On Geography Lessons and Civil War Cartography

–

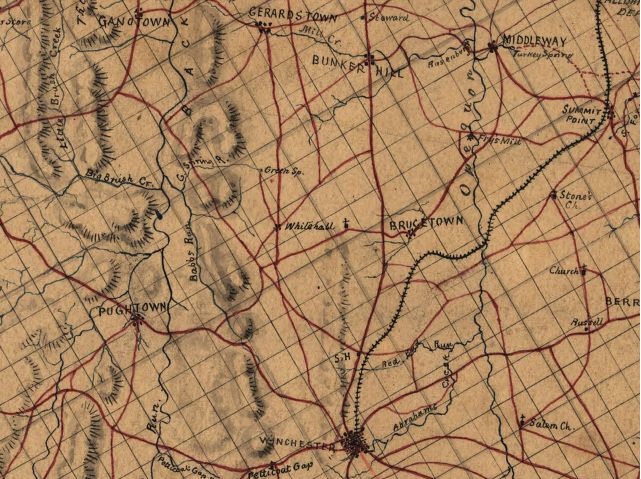

The highlight of the first five chapters of Two Great Rebel Armies by Richard M. McMurray was hands down the lesson on geography. This is, I fear, an area that receives too little emphasis in our study of the war. Particularly interesting was the reference to the Shenandoah Valley (Valley of Virginia) and the advantages and disadvantages it presented to those who chose to maneuver in it. It helps me to actually “see” a map of the area and I found a collection that you might find helpful if you’ve not already discovered it. It is the Hotchkiss Collection on the Library of Congress site here. The collection consists of 341 sketchbooks, manuscripts, and annotated printed maps, the originals of which reside in the Library of Congress’ Geography and Map Division. It also provides two essays including a biographical essay about Hotchkiss. Not to be missed is the Map of the Shenandoah Valley which was considered a masterpiece.

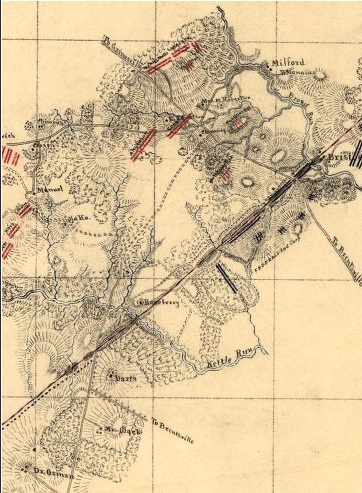

Sketch of the Battle of Bristoe, Wednesday, Oct. 14, 1863 / by Jed. Hotchkiss, Capt. & Top. Engr., 2nd Corps, A.N.Va. (Library of Congress)

Major Jedediah Hotchkiss (1828-1899) was considered the cartographer of the Army of Northern Virginia. He was a topographic engineer in the Confederate Army. Most of the works in the collection are of the Shenandoah Valley and certainly some would have been used by Lee and his commanders.

Jedediah Hotchkiss

The letters of Jedediah Hotchkiss are available on the University of Virginia’s excellent The Valley of the Shadow digital history project here. This exceptional collection is well worth the read and covers the major’s war experiences from 1861 – 1864 as conveyed to his family.

Solving a Civil War Photograph Mystery

Grant at Center Point (Careful!) LC-DIG-ppmsca-15886 (digital file from original photograph) , LC-USZ62-21992 (b&w film copy neg.)

The Library of Congress has a new entry in their always fascinating Civil War Photographs section. They challenge the authenticity of the photo above which the owner of the copyright, Levin C. Handy (1855-1932) and nephew of Mathew Brady, claims to be General Grant at Center Point, Virginia. They step the reader through their discovery process which reveals …. well I won’t spoil it for you. Find out for yourself how this photo was created here.

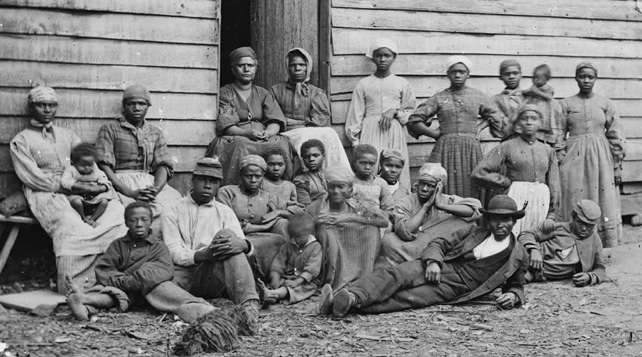

On Slavery – 6 Chattels Personal

Kenneth Stampp’s chapter “Chattels Personal” is excellent. I suspect that “chattel” is not a word most of us learn unless we study law or Antebellum American history in depth. Its meaning in the context of slavery is, of course, that person’s slaves were consider legally as “chattel personal.”

Being a person quite taken with words, I did a little research on the origins of this one and found it informative. Interestingly, a search for the etymology of the word found some disagreement. The following perspective comes from French: A Linguistic Introduction.

“Chattel comes from the French noun cheptel used to designate all movable property, but now is restricted to ‘livestock’. English has gone a step further: cattle used to designate any movable property, then all livestock, and now is generally restricted to bovines. English also has the word chattel, legally any type of movable property, but more specifically in modern usage, it refers to slaves. All of these terms are ultimately derived from the Latin word capitalis, which has been reintroduced in modern financial vocabulary, e.g. capital campaign in fundraising. This term, in turn, is derived from the Latin word caput, ‘head’ (French chef), with the result that ‘head of cattle’, our original example, ultimately is a ‘head of things with heads’!” [1]

This from A New Law Dictionary and Glossary…

“…the singular chattel seems to be immediately formed from the Fr. chatelle, or chatel, (q.v.); the plural chattels, (or, as it was formerly written, catals,) is supposed to be derived from the L. Lat., catalla, the ch being pronounced hard, as in the word charta, which is evident from the form of the old Norman plural, cateux, (q.v.). As to any further derivation, catalla or catalia is clearly shown by Spelman to be merely a contracted form of writing capitalia, which with the singular capitale, or captale, occurs frequently in the Saxon and early English laws. The primary meaning of capitalia was animals, beasts of husbandry, (otherwise call averia, q.v.) or cattle; in which last word it is still identically retained.

Capitalia is derived by Spelman from capita, heads; a term still popularly applied to beasts, as “so many “heads of cattle.” When the word took the form catalla, it continued to retain this primary meaning, but gradually acquired the secondary sense of movables of any kind, inanimate as well as animate, and finally became used to signify interests in lands.”

CHATTELS PERSONAL, otherwise called THINGS PERSONAL, comprise all sorts of things movable, as good, plate, money, jewels, implements of war, garments, animals and vegetable productions; as the frit or other part of a plant, when severed from the body of it, or the whole plant itself, when severed from th ground. Besides things moveable, they include also certain incorporeal rights or interestes, growing out of, or incident to them, such as patent rights and copyrights…” [2]

——

[1] French: A Linguistic Introduction

By Zsuzsanna Fagyal, Douglas Kibbee, Fred Jenkins

Published by Cambridge University Press, 2006

ISBN 0521821444, 9780521821445

337 pages (pp. 154-155), Accessed online, November 16, 2008, http://books.google.com/books?id=4yTA6SvGuekC&pg=PP1&dq=French:+A+Linguistic+Introduction#PPA154,M1

[2] A New Law Dictionary and Glossary

By Alexander M. Burrill

Published by The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 1998

ISBN 1886363323, 9781886363328

1099 pages (pp. 207-208), Accessed online, November 16, 2008, http://books.google.com/books?id=DeQYXYMBtwgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=etemology+of+the+word+chattel#PPA208,M1

Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South.

Stewards of Civil War Railroads – Part III

This post completes the series, Stewards of Civil War Railroads. Read Part I here and Part II here.

Above: Group of the Construction Corps U.S. Mil. R. Rds., with working tools, etc., Chattanooga, Tennessee

Courtesy of Library of Congress: LC-USZ62-62364

Millett and Maslowski posit that President Abraham Lincoln did not have Jefferson Davis’ sensitivity about government interference with railroads. The evidence supports the point and also suggests that Davis’ hands-off approach expanded to other areas under his purview including signals and communications. Whether he was afflicted with chronic indecisiveness or was bowing to the perceived whims of a public unreceptive to “big government” is open for discussion but as in many things, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Regardless, it is clear that rational military considerations were not the sole concern in shaping the South’s military policies and programs. Had they been so, military needs would have received higher priority and the events of the war may have flowed differently.

Above: Lincoln and McClellan

The impact of the decision making processes in the Lincoln and Davis administrations and the respective Congresses as regards those issues impacting the military is indeed a fascinating one and worthy of continued analysis and review. Clearly the social, economic, and political nuances of the North versus the South had much to do with the directions taken within each section. But one is left to wonder whether the leadership qualities of Lincoln and Davis, including the ability to be decisive, allowed the North to more frequently follow a path guided by rational military reason.

Above: The engine “Firefly” on a trestle of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.

American Historian: George Bancroft

I’m back from Christmas break and trying to recuperate from a few too many cinnamon rolls. Reading assignments and preparation of a research proposal due Sunday are top of mind.

The class is Historiography so the research isn’t to be about the development and proof of a thesis. It’s more about research into the history of how history was written.

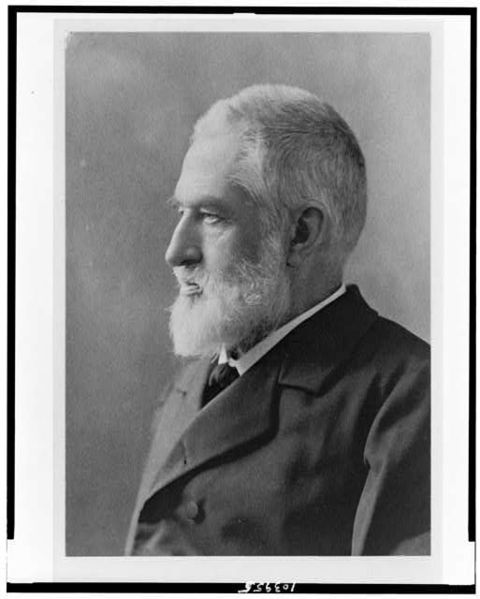

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

Bancroft was one of the best known American historians of the 19thcentury. While Harvard educated (he entered at 13 and graduated at 17!), he is considered a “literary historian,” who wrote in a style popular with  the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

Perhaps less known is that Bancroft, while Secretary of the Navy, created the Naval Academy. He was also chosen by Congress to eulogize Abraham Lincoln. The New York Times reprinted that Eulogy on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the event in 1915. It, along with drawings of the event, can be seen in their entirety here.

I have located the index to his papers housed on microfiche at Cornell University and two biographies which leverage that material. The first, a two volume set 1971 reprint of M.A. DeWolfe Howe’s 1908 work The Life and Letters of George Bancroft, I was able to find on the Amazon Marketplace in almost pristine shape. The second, George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel, was written by Russel B. Nye and published in 1945. It’s on order. There are other large collections of Bancroft materials in holdings by the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. I’m beginning in earnest a search for articles that deal with his contributions to American history as well.

As a follow-up at some later point, I think it would be very interesting to contrast the style and impact  of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

You might recall that Charles and Mary Beard were the first to suggest that the Civil War was the second American revolution as was mentioned in my previous post here.

The exceptional oil on canvas portrait above of Bancroft in later life was painted by Gustav Richter, a German painter (1823 – 1884). It is a part of the Harvard University Portrait Collection and is on display at Memorial Hall.

More as I get into my research.

Photo credits:

Photo of George Bancroft in middle age taken by Mathew Brady, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo of painting above: The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Exploring Causes of the Civil War – Part III – The Antebellum South

The Southern man aspired to a lifestyle that had, as utopian model of success, the English country farmer. Jeffersonian agrarianism was valued over Hamiltonian industrialization.

To achieve success, cheap labor in the form of slavery was embraced. The capital of the south was invested in slaves even after modernized farming equipment became available. More land was needed to produce more crops which required, in turn, more slaves. This cycle repeated until some 4 million slaves populated the South by mid-century. The system became self-perpetuating because – as posited by historian James McPherson – slavery undermined the work-ethic of both slave and Southern whites. The slave obviously had limited opportunity for advancement. Manual labor became associated with bondage and so lacked honor. The result was a limited flow of white immigrants to the south who could provide an alternative labor force and an increase in the migration of southern whites to free states.[i]

became associated with bondage and so lacked honor. The result was a limited flow of white immigrants to the south who could provide an alternative labor force and an increase in the migration of southern whites to free states.[i]

Simply stated, the South chose not to modernize. It hosted little manufacturing. It also lacked a well developed transportation system (a fact that would prove key to the conduct of the war).

White supremacy was simply a fact. Part of the responsibility of owning slaves was to care for their material needs as you would children. White southern children grew up with a facility for “command” and became a part of what was viewed by many as a southern aristocracy.[ii]

According to historian Avery Craven, “three great forces always worked toward a common Southern pattern. They were:

- a rural way of life capped by an English gentleman ideal,

- a climate in part more mellow than other sections enjoyed, and

- the presence of the Negro race in quantity. More than any other forces these things made the South Southern.”[iii]

Next post – The Antebellum North

For additional reading…

On Jeffersononian Agrarianism see the University of Virginia site here.

[i] James. M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 10., 41.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Avery Craven. The Coming of the Civil War. 2nd Ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 33.

Photo Credits:

Watercolor View of the West Front of Monticello and Garden (1825) by Jane Braddick. Peticolas. The children are Thomas Jefferson’s grandchildren. Public Domain [Source: Wikipedia Commons]

Inspection and Sale of a Slave. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Digital ID: cph 3a17639 Source: b&w film copy neg.

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-15392 (b&w film copy neg.)

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Bits of white paper strewn across a prearranged site announced the meeting of the brotherhood. Held at night, in keeping with the secrecy that shrouded its early years, the sessions of the local chapters of the Order of the Star Spangled Banner were open only to initiates and those about to join them in the ranks. The ritual for admission to the lodge seemed endless. But instead of irritating men tired after a long day’s work, the elaborate raps and special handclasps, the passwords between brothers, and the sentinels sent to escort candidates long known to the membership seemed to heighten the feeling of camaraderie, the sense of special excitement at the dangerous but essential mission they were privileged to share. For they were there to save and cleanse the nation, to preserve for themselves that abstraction which some would later call the American dream.

Bits of white paper strewn across a prearranged site announced the meeting of the brotherhood. Held at night, in keeping with the secrecy that shrouded its early years, the sessions of the local chapters of the Order of the Star Spangled Banner were open only to initiates and those about to join them in the ranks. The ritual for admission to the lodge seemed endless. But instead of irritating men tired after a long day’s work, the elaborate raps and special handclasps, the passwords between brothers, and the sentinels sent to escort candidates long known to the membership seemed to heighten the feeling of camaraderie, the sense of special excitement at the dangerous but essential mission they were privileged to share. For they were there to save and cleanse the nation, to preserve for themselves that abstraction which some would later call the American dream.

![[Charleston Harbor, S.C. Deck and officers of U.S.S. monitor Catskill; Lt. Comdr. Edward Barrett seated on the turret].](https://i0.wp.com/memory.loc.gov/service/pnp/cwpb/02900/02975r.jpg)