Archive for the ‘Civil War as Revolution’ Category

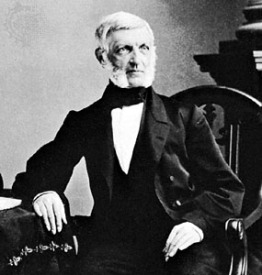

American Historian: George Bancroft

I’m back from Christmas break and trying to recuperate from a few too many cinnamon rolls. Reading assignments and preparation of a research proposal due Sunday are top of mind.

The class is Historiography so the research isn’t to be about the development and proof of a thesis. It’s more about research into the history of how history was written.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

Bancroft was one of the best known American historians of the 19thcentury. While Harvard educated (he entered at 13 and graduated at 17!), he is considered a “literary historian,” who wrote in a style popular with  the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

Perhaps less known is that Bancroft, while Secretary of the Navy, created the Naval Academy. He was also chosen by Congress to eulogize Abraham Lincoln. The New York Times reprinted that Eulogy on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the event in 1915. It, along with drawings of the event, can be seen in their entirety here.

I have located the index to his papers housed on microfiche at Cornell University and two biographies which leverage that material. The first, a two volume set 1971 reprint of M.A. DeWolfe Howe’s 1908 work The Life and Letters of George Bancroft, I was able to find on the Amazon Marketplace in almost pristine shape. The second, George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel, was written by Russel B. Nye and published in 1945. It’s on order. There are other large collections of Bancroft materials in holdings by the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. I’m beginning in earnest a search for articles that deal with his contributions to American history as well.

As a follow-up at some later point, I think it would be very interesting to contrast the style and impact  of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

You might recall that Charles and Mary Beard were the first to suggest that the Civil War was the second American revolution as was mentioned in my previous post here.

The exceptional oil on canvas portrait above of Bancroft in later life was painted by Gustav Richter, a German painter (1823 – 1884). It is a part of the Harvard University Portrait Collection and is on display at Memorial Hall.

More as I get into my research.

Photo credits:

Photo of George Bancroft in middle age taken by Mathew Brady, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo of painting above: The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

The Civil War as Revolution – Part V

[Note: This post continues a series on The Civil War as Revolution which is available at the following links: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

————-

In the last post, I discussed challenges to the revolutionary nature of the American Civil War by historical revisionists. A second challenge was made by historical economists who contended that the Civil War caused an economic slowdown, not acceleration. Historian James McPherson counters that it is inappropriate to examine the economics of the country as a whole during the war because it so utterly devastated the economic resources of the south. He posits that the North saw economic growth during the war and that “after the war the national economy grew at the fastest rate of the century for a couple of decades, a growth that represented a catching-up process from the lag of the 1860s caused by the war’s impact on the South.”[i]

In the last post, I discussed challenges to the revolutionary nature of the American Civil War by historical revisionists. A second challenge was made by historical economists who contended that the Civil War caused an economic slowdown, not acceleration. Historian James McPherson counters that it is inappropriate to examine the economics of the country as a whole during the war because it so utterly devastated the economic resources of the south. He posits that the North saw economic growth during the war and that “after the war the national economy grew at the fastest rate of the century for a couple of decades, a growth that represented a catching-up process from the lag of the 1860s caused by the war’s impact on the South.”[i]

The third challenge to the Civil War as revolution addressed the plight of Southern blacks and contested that they saw little or no change in their circumstances after both emancipation and the Southern surrender.

Some argued that the Republican Party’s commitment to equal rights for freed slaves was superficial, flawed by racism, only partly implemented, and quickly abandoned. Other

historians maintained that the policies of the Union occupation army, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the national government operated in the interests of the white landowners rather than the black freedmen, and that they were designed to preserve a docile, dependent, cheap labor force in the South rather than to encourage a revolutionary transformation of land tenure and economic status. And finally another group of scholars asserted that the domination of the southern economy by the old planter class continued unbroken after the Civil War.[ii]

But McPherson considers these arguments flawed suggesting that they reflect “presentism,” “…a tendency to read history backwards, measuring change over time from the point of arrival rather than the point of departure.”[iii] He points out that dramatic change did occur and the statistics prove it out. “When slavery was abolished, about 90 percent of the black population was illiterate. By 1880 the rate of black illiteracy had been reduced to 70 percent, and by 1900 to less than 50 percent. Viewed from the standpoint of 1865 the rate of literacy for blacks increased by 200 percent in fifteen years and by 400 percent in thirty-five years.”[iv]

Emancipation had equally dramatic economic impacts. It amounted to nothing less that the “confiscation of about three billion dollars of property – the equivalent as a proportion of the national wealth to at least three trillion dollars in 1990.”[v]

In effect, the government in 1865 confiscated the principal form of property in one-third of the country, without compensation. That was without parallel in American history – it dwarfed the confiscation of Tory property in the American Revolution. When such a massive confiscation of property takes place as a consequence of violent internal upheaval on the scale of the American Civil War, it is quite properly called revolutionary.[vi]

McPherson sites other economic impacts of emancipation including the redistribution of income in the South post war which “was by far the greatest in American history.”[vii] Equally dramatic was the change in political power in the post war South that resulted from the freeing of the slaves. Blacks achieved the vote in 1868 and within a year represented the majority of registered voters. In four years, 15 percent of the officeholders in the South were black. [viii] “In 1870, blacks provided three-fourths of the votes in the South for the Republican party, which controlled the governments of a dozen states in which five years earlier most of these black voters had been slaves. It was this phenomenon, more than anything else, that caused contemporaries to describe the events of those years as a revolution[ix] This fact caused the pendulum of thought to swing back in the 1980s to support of the Civil War and Reconstruction experiences as revolutionary.

Historian Eric Foner calls the post war period in history “Radical Reconstruction” and found it unequaled in history in its support of the black laborer and th eir political rights. Regrettably, some of the gains made were reversed by the counterrevolution that followed when the Democratic Party was revived in the north and the indifference of the Republicans of the north toward blacks in the south increased. But, as McPherson points out, “the counterrevolution was not as successful as the revolution had been.” Blacks in the south remained free, continued to have the vote, could still own land, and could still go to school.[x]

eir political rights. Regrettably, some of the gains made were reversed by the counterrevolution that followed when the Democratic Party was revived in the north and the indifference of the Republicans of the north toward blacks in the south increased. But, as McPherson points out, “the counterrevolution was not as successful as the revolution had been.” Blacks in the south remained free, continued to have the vote, could still own land, and could still go to school.[x]

_________________

Note: I highly recommend historian Eric Foner’s website for access to a number of his articles and to his lectures on the Columbia American History Online (CAHO) site. You can register for a free trial subscription to CAHO.

Photos: First: Ruins seen from the capitol, Columbia, S.C., 1865. Photographed by George N. Barnard. National Archives Ref. # 165-SC-53. Second: Several generations of a family are pictured on Smith’s Plantation, South Carolina, ca. 1862. (Library of Congress)

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

Share it!

[i] James McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press), 11., [ii] Ibid., 14., [iii] Ibid., 16., [iv] Ibid. [v] Ibid., 17. McPherson sites studies by Roger Ransom and Richard Sutch., [vi] Ibid., 17-18., [vii] Ibid., 18., [viii] Ibid., 19., [ix] Ibid., [x] Ibid., 23.

The Civil War as Revolution – Part I

[Note: This post is part of a series on The Civil War as Revolution which is available at the following links: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

————-

Earlier this month, I posted some thoughts on Abraham Lincoln as revolutionary. It ties to one of the topics we were asked to consider this term, whether the Civil War should be considered the second American revolution. I suspect it is an essay question in many American history programs dealing with the Civil War. I’d like to explore this over the next several posts. A proper place to start is with the question, what is revolution?

![Fist [Source Wikopedia Commons]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Fist.png/421px-Fist.png) According to William A. Pelz in his study on the history of German social democracy, “revolution” comes from the German word “Ugmwälzung” which means “rotation,” as in the turning of an axle. He posits that “in the socio-political realm, revolution means the displacement of a state, governmental, social and economic system by another, higher, more developed state, governmental, social and economic system… Two things are essential to the concept of revolution: that the rotation (Ugmwälzung) be comprehensive and fundamental–that everything old and antiquated be thrown out, weeds torn out by their roots; that a higher and better state replace that which has been done away with. Both conditions must be maintained.”[i] Thus social revolution results in nothing less than transformation.

According to William A. Pelz in his study on the history of German social democracy, “revolution” comes from the German word “Ugmwälzung” which means “rotation,” as in the turning of an axle. He posits that “in the socio-political realm, revolution means the displacement of a state, governmental, social and economic system by another, higher, more developed state, governmental, social and economic system… Two things are essential to the concept of revolution: that the rotation (Ugmwälzung) be comprehensive and fundamental–that everything old and antiquated be thrown out, weeds torn out by their roots; that a higher and better state replace that which has been done away with. Both conditions must be maintained.”[i] Thus social revolution results in nothing less than transformation.

- Painting by Eugene De la Croix (Charenton-Saint-Maurice, 1798 – Paris, 1863) July 29, Liberty guiding the people. Musée du Louvre. Public Domain

Pelz offers two examples of undisputable social revolution. The first, not surprisingly, is the French Revolution, “…the revolution par excellence…that swept away the last remains of medieval feudalism and created the foundation of modern bourgeois society.”[ii] The second example – though hardly resembling the first – was none the less more profound. It was triggered by “the introduction of machine work, which fundamentally altered the nature of work and thereby the basis of state and social life. Every sphere of human existence was penetrated by this revolution (Umwälzung). These two organically related revolutions (Umwälzungen) born of the same impetus, only manifesting themselves differently, are probably the most important revolutions known to history. They toppled and purged from top to bottom and brought humanity forward with a violent jolt.”[iii]

Revolution in politics has been described as “fundamental, rapid, and often irreversible change in the established order.”[iv]

- Da Vinci

Revolution involves a radical change in government, usually accomplished through violence[,] that may also result in changes to the economic system, social structure, and cultural values. The ancient Greeks viewed revolution as the undesirable result of societal breakdown; a strong value system, firmly adhered to, was thought to protect against it. During the Middle Ages, much attention was given to finding means of combating revolution and stifling societal change. With the advent of Renaissance humanism, there arose the belief that radical changes of government are sometimes necessary and good, and the idea of revolution took on more positive connotations. John Milton regarded it as a means of achieving freedom, Immanuel Kant believed it was a force for the advancement of mankind, and G.W.F. Hegel held it to be the fulfillment of human destiny. Hegel’s philosophy in turn influenced Karl Marx.[v]

Historian James McPherson offers the following as a “common sense” definition for revolution: “an overthrow of the existing social and political order by internal violence.”[vi] With this as background the question becomes, does the American Civil War qualify for revolution status? Was it sufficiently transforming?

- Mark Twain

More in tomorrow’s post but let me leave you with this quote from Mark Twain.

No people in the world ever did achieve their freedom by goody-goody talk and moral suasion: it being immutable law that all revolutions that will succeed must begin in blood, whatever may answer afterward.

– A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

Copyright © 2007 Rene Tyree

[Addendum: This series on The Civil War as Revolution continues at the following links: , Part II, , Part III,, Part IV, Part V, The Revolutionaries of the American Civil War, and Cogitating on Abraham Lincoln as Revolutionary.]

[i] Pelz, William A. and William A. Pelz, eds. Wilhelm Liebknecht and German Social Democracy: A Documentary History. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994), 264-265, Book on-line. Available from Questia, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=15096547. Internet. Accessed 13.October 2007.

[ii] Ibid., 265.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Encyclopedia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2007

[v] Ibid.

[vi] James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 16.

![Photo of Unfinished portrait miniature of Oliver Cromwell by Samuel Cooper Public Domain [Wikipedia]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/17/Cooper%2C_Oliver_Cromwell.jpg)

![Wikipedia Commons]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a0/Declaration_of_Human_Rights.jpg)

![King George III in Coronation Robes Public Domain [Wikipedia Commons]](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b1/George_III_in_Coronation_Robes.jpg)