Archive for the ‘Historians’ Category

WWII Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West Premiering May 6 on PBS

In an earlier post, I mentioned that I’d been contacted by a publicist at PBS to preview the upcoming documentary that begins airing this week (May 6th), WWII Behind Closed Doors. I’ve had a chance to watch the full documentary and found it fascinating.

When I think of PBS, I think of credibility. Add credibility to reenactments performed by an extremely talented cast, the drama of war on a global scale, and the intrigue of information hidden from the public for decades, and the result makes for excellent viewing.

The story largely centers around Joseph Stalin – his hatred of Poland, betrayal by Hitler, paranoia and its impact on his leadership cadre, dealings with Churchill and Roosevelt, and hand in decisions that doomed millions. It also depicts how a few leaders determine the fate of nations. The deception around Stalin’s atrocities against Poland, these lies perpetuated by England and the United States, is startling. Another of the documentary’s highlights is its presentation of the war from the view of the Poles.

This from the publicist…

Rare wartime documents made briefly available only after the fall of the Soviet Union help reveal the real story of confidential meetings held during the war between c. Award-winning historian and filmmaker Laurence Rees (Auschwitz: Inside the Nazi State, Nazis – A Warning from History) tells the hidden story of Stalin’s back room dealings – first with the Nazis and then with Roosevelt and Churchill. By juxtaposing conventional documentary elements with dramatic recreations, WWII Behind Closed Doors breaks through the myths of the Allied powers, illuminating the hidden motivations of “The Big Three” and creating a dynamic reappraisal of one of the seminal events in world history.

View an excellent video on the making of the series here.

For full information on each episode and a wealth of additional information, see the PBS program site here or by clicking on the image below.

For more information on Laurence Rees, see his website here or by clicking on the image below.

For the Common Defense

Peter Maslowski and Allan R. Millett. For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America. Enlarged edition. Simon & Schuster, 1994. See the book on publisher’s site here.

This monumental survey of American military history has three stated purposes. The first is to analyze the development of military policy. The second is to examine the characteristics and behavior of the United States armed forces in the execution of that policy and the third is to illuminate the impact of military policy on America’s international relations and domestic development. Millett and Maslowski propose that there are six major themes that position military history within the larger context of American history. These include the following and are quoted from the text.

- Rational military considerations alone have rarely shaped military policies and programs. The political system and societal values have imposed constraints on defense matters.

- American defense policy has traditionally been built upon pluralistic military institutions, most

notably a mixed force of professionals and citizen-soldiers.

notably a mixed force of professionals and citizen-soldiers. - Despite the popular belief that the United States has generally been unprepared for war, policy makers have done remarkably well in preserving the nation’s security.

- The nation’s firm commitment to civilian control of the armed forces requires careful attention to civil-military relations.

- The armed forces of the nation have become progressively more nationalized and professionalized.

- Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, but especially during the twentieth century, industrialization has shaped the way the nation has fought.

The authors further suggest that Americans do not consider themselves a warring people but have in fact become involved in a number of conflicts and that because of this, the study of the United States’ military history is important in if one hopes to gain better insight into both America’s history and its current and future identity.

Millett and Maslowski structure their book chronologically, which is completely fitting. They begin with a survey of colonists from 1609 – 1689. They devote a chapter as well to the Colonial Wars that occurred between 1689 and 1763. The American Revolution follows and includes the years between 1763 and 1783. Two chapters cover the military history of the new republic including its expansion. This includes the period 1783 – 1860 after which the country is on the precipice of civil war. Two chapters are devoted to the American Civil War the first focusing on the early years of 1861 and 1862. The second surveys the years between 1863 and the war’s end in 1865. And so the format continues covering major years of either military growth or conflict through to two great wars. Several chapters are devoted to the period spanning the Cold War during which the Korean War took place. The Vietnam War covers the period from 1961 – 1975. The periods marking the end of the Cold War follow and then a chapter is devoted to the Gulf War.The book was written and published in its revised format prior to the Iraq War.

Millett and Maslowski’s work provides outstanding bibliographies expanded in the revised edition to include selected references at the end of every chapter as well as a generous General Bibliography. It also includes an excellent set of illustrations and photographs. This work is intended for students of American military history and American history in general. It should also appeal to the reader who wants a perspective on the events of world history in which the American military has been engaged.

Both authors bring impeccable credentials to their authorship of this text. Allan R. Millett (see his 2007 vitae here) is the Raymond E. Mason Jr. Professor Emeritus of History from The Ohio State University. He is the Stephen Ambrose Professor of History at the University of New Orleans and Director of the Eisenhower Center  for American Studies at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. He received his B.A. in English from DePauw University and his M.A. and Ph.D. in History from The Ohio State University. He is a retired colonel of the Marine Corps Reserve, and a specialist in the history of American military policy and 20th century wars and military institutions. He is one of the founders of the military history program at The Ohio State University. Dr. Millett was recently honored with the 2008 Pritzker Military Library Literature Award for Lifetime Achievement in Military Writing (see the news release here).

for American Studies at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. He received his B.A. in English from DePauw University and his M.A. and Ph.D. in History from The Ohio State University. He is a retired colonel of the Marine Corps Reserve, and a specialist in the history of American military policy and 20th century wars and military institutions. He is one of the founders of the military history program at The Ohio State University. Dr. Millett was recently honored with the 2008 Pritzker Military Library Literature Award for Lifetime Achievement in Military Writing (see the news release here).

Peter Maslowski is Professor of History at the University of Nebraska where he specializes in the history of the Civil War, military, and Vietnam War. He received his B.A. from Miami University and M.A. and Ph.D. from The Ohio State University. Professor Maslowski served as the John F. Morrison Professor of Military History at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff from 1986 to 1987. In 2002, Professor Maslowski, a highly regarded teacher/lecturer, received the Outstanding Teaching and Instructional Creativity Award (OTICA). He is on the Advisory Board of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. For an excellent interview with Professor Maslowski on his career, see the 2005 interview in the Daily Nebraskan here

I have found no other resource on U.S. Military History that is so comprehensive in nature. Recommend.

Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea

Belatedly, I want to mention that I’ve received a pre-publication copy of Noah Andre Trudeau’s Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea, which I’ll hope to provide a full review of before too long. At first blush, it appears to be an excellent read.

Since this book falls into the category of Civil War Campaigns, I’ve added a shelf in my virtual bookstore to accommodate it which you can find here.

As a student of military history, one of the many things that I find so fascinating about Sherman’s march is that its destructive power encourages its consideration as “total war” a la Clausewitz. Can’t wait to dig in to this one.

For those of you in the Chicago area, Mr. Trudeau’s publisher Harper Collins, indicates that he will be publicizing his book at the following on Thursdays.

05:00 PM – 07:30 PM

PRITZKER MILITARY LIBRARY

2nd FL 610 N Fairbanks Court Chicago, IL 60611

May Civil War and Military History Book Acquisitions – II

Continuing with my May book acquisitions which illustrate, as said by Civil War Interactive’s comments on my blog this week, why bank robbery may be needed to support my book-buying habits…

This looks like a great read. Author Tom Wheeler, an accomplished man by any measure, has a terrific website here with more about his book and research. This has moved to the top of my list of reading for between terms.

I have DISCOVERED Dr. Hess and the growing list of terrific titles he has published on the Civil War. No doubt his other books will show up in my library before long. Dr. Hess, who has impressive academic credentials, has a website here. His book, Pickett’s Charge: The Last Attack at Gettysburg, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

I’ve been intending to pick this up. Authored by military history professor and fellow blogger Mark Grimsley, it too is at the top of my reading list. Dr. Grimsley’s OSU webpage is here. His blog is here.

My post, “Fabian Strategy and the American Civil War” here, lead me to this book. One of my readers recommended it and suggests that it proves that the Confederacy could not have used the Fabian strategy effectively. I’m looking forward to this one.

Jav Luvaas is another prolific writer of military history and my collection of his books is growing. I first discovered his work while taking the course, Great Military Philosopers (see “The Courses” page here for details. I picked up his titles: Napoleon on the Art of War and Frederick the Great on the Art of War.

I’ll be adding these authors to my “The Historians” page shortly.

Academic Book Review – George Bancroft

George Bancroft. By Russel B. Nye. New York: Washington Square Press, Inc. 1964. Bibliography. Pp. x, 212. $.60.

If biographies written in the twenty-first century tend toward tomes, Russel Nye’s 1964 work on George Bancroft, the most acclaimed American historian of the nineteenth century, demonstrates how to impress with a modicum of words. Though Bancroft’s life spanned almost a century, Nye skillfully paints a portrait of the man against the sweeping landscape of the United States’ passage from fledgling country at the turn of 18th century to battle-scarred nation ninety years later, all in fewer than two hundred pages.

Nye’s book is part of the Washington Square Press “Great American Thinkers Series,” targeting an audience of general readers as well as serious secondary and college students who want readable history. George Bancroft as subject is in good company among other well known Americans included in the series, like Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John C. Calhoun. Series editors provided a general outline for Nye to follow, which included a short biography of the subject, a critical evaluation of his central ideas, and his influence upon American thought as a whole.

Nye approaches the task in a somewhat unconventional manner. He begins and ends with reasonably standard material. A chronology of key events in Bancroft’s life is placed in the front matter of the book, beginning with his birth in 1800 and ending with his death in 1891. End materials include a list of Bancroft’s extensive published works and a complete bibliography and index. It is in the book’s narrative that Nye shows structural creativity. He reveals Bancroft by coming at the subject from six different directions: life history, views on education, artistic and cultural perspectives, formation as a politician, views on humanity and the divine, and Bancroft’s contribution to historiography.

The first chapter, titled “The Pattern of a Life,” provides a highly readable narrative overview of Bancroft’s ninety-one years. Nye begins with the family and culture into which Bancroft was born, and then explores his passage through school years, including entry into Harvard at the age of 13. His formative years studying abroad are covered next, and insight is provided into the effects that European intellectuals and artists had on the now young man. Nye brings Bancroft home to the United States, doctorate in hand, and traces his quest for direction in life that leads him away from ministry and into politics and writing. His life as politician and as an emerging and then accomplished historian are described, as well as the events that bring a close to Bancroft’s life.

Nye devotes the entire second chapter, “Experiment at Round Hill,” to Bancroft’s daring project as schoolmaster of a preparatory school for boys in New England. Partnering with a colleague from Harvard, Bancroft incorporates in the endeavor the progressive concepts in education he observed while in Europe. But Bancroft has a love-hate relationship with teaching, and gradually realizes that his destiny lies elsewhere. As the chapter closes, he has sold his interest in the school to his partner and moved on, having left his mark on the history of American education as the creator of the first high school and a modeler of educational reform.

In the third chapter, “The Anatomy of Culture,” Nye explores the Romantic Movement’s impact on Bancroft and his contemporaries, and makes good use of the subject’s actual writing. Excerpts of Bancroft’s early attempts at poetry are presented by way of showing that, while his own poetic work was amateurish, he was able to channel his love for art into the role of literary critic, becoming quite adept at it. Nye does a masterful job of showing, through excerpts of Bancroft’s reviews and critiques, not only his appreciation of the artistic, but his gift for seeing broad themes like democracy in art. He also shows how Bancroft was able to bring his interest in artistic judgment and creation to his growing preoccupation with history. Instead of losing touch, “he absorbed his interest in art into the larger context of his theory of culture and his concept of history. To him, as to his contemporaries, the boundaries of intellectual specialization were fluid” (63). This fusion of the literary with history defined Bancroft’s historical writing. Nye’s ability to correlate the cultural milieu of early 19th century with Bancroft’s growth as philosopher, theologian, artistic critic, and historian is particularly well done.

Chapter 4, “The Fabric of American Political Life,” guides the reader through Bancroft’s life as a politician, and his metamorphosis into a Jacksonian democrat and political thinker. Again, Nye identifies themes from Bancroft’s writings and personal correspondence, including the idea that political figures are heroes to the populations they serve. Nye closes the chapter with a moving description of Bancroft’s role as eulogizer of Lincoln, a man who Bancroft grew to consider as a hero of some stature through the course of the Civil War. He also traces Bancroft’s evolving views on slavery.

In Chapter 5, “Nature: Human and Divine,” Nye explores how Bancroft came to his religious beliefs and his philosophical stand on the nature of humanity and the divine. This is an important topic because Bancroft’s theological thinking informed much of his historical writing and speaking. Nye shows Bancroft as a man of his times, influenced by the enthusiasm of a country running toward a bright future, and yet a man who contributed much to that nation because of his study abroad and exposure to many of the world’s foremost thinkers. Nye does a good job of showing how Bancroft reconciled his belief in man’s free will as long as it was exercised within the larger will of the divine.

In his final chapter, “The Shape and Meaning of History,” Nye looks as Bancroft the historian and the influence of his historiography. He provides an excellent overview of the state of historical study at the turn of and into the early 19thcentury, contrasting rationalistic historical theory against Romantic history a la Rankian Zeitgeist. His review of the expectations of historical writers in Bancroft’s generation is excellent. But most important in this chapter are the selections from Bancroft’s own essays, illustrating how he conceived of his own calling. His personal philosophy, which he put to paper not long after returning from studies in Europe, placed the office of the historian second only to the poet in its noble call to find God within history.

This perspective, Nye informs, pervaded the first three volumes of Bancroft’s most famous work, The History of the United States of America from the Discovery of the Continent, in which it was clear “that he was convinced that the United States was the creation of Divine Providence” (158). The second theme was that of man’s right to pursue freedom. Nye takes the reader through the completion and then revision of the seven volumes which took place over the course of most of Bancroft’s remaining life. He touches upon the influences of the American Civil War on his writing, and particularly on the volumes having to do with the Revolutionary War. Nye gives insight into Bancroft’s work style and ethic, as reflected in a two-volume work on the American Constitution. He interjects some deserved criticism of Bancroft who, he suggests over simplified the events surrounding the Constitution’s creation, ignoring “the whole tangled skein of economic and political rivalries, conflicting interests, and clashing personalities” (170).

Nye leaves the reader with a sense for Bancroft’s brilliance across a broad range of diverse interests. He paints him as a man who enjoyed the privileges of an education well beyond the norm of his day, and earned by an innate drive and love for scholarship. Nye’s Bancroft was comfortable with life choices that went against the norm, an indication of independent thought. But he was also a man of his times, influenced by the great thinkers of his era and yet contributing one of the most important voices of the nineteenth century. He brought to his generation a better sense of the American story, and to a large degree, popularized history with the first complete treatment of the United States through its inception as a nation. He was guided by a strong belief in divine providence and its hand upon America. But at his core, he was, as depicted by Nye, a scholarly man of letters – a distinction I suspect would have pleased Mr. Bancroft. His legacy is a remarkable body of work sadly forgotten by most citizens of the 21st century because of changing standards in historiography.

Nye does a masterful job of identifying Bancroft’s core beliefs and the influences that formed the man and his career. He also shows a considerable grasp of the nuances of both history and historiography that were in play in the 19thcentury – worth noting because Nye’s training is in literature rather than history. Like all series authors, Nye brings to the work a Ph.D. An English professor at Michigan State University, he might seem like an odd choice to profile a historian, but he proves himself equal to the task, perhaps because biography straddles both history and literature. His obvious mastery of the large collection of papers Bancroft left behind for his biographers is impressive.

Russel Nye was awarded the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for Biography for this work. Is there a better recommendation?

Rene Tyree

American Military University

Photo credit: Einstein at 42 from Wikipedia Commons. Public Domain

New Pages

As my studies progress, I’ve found need of several more pages on the blog. Those of you who roam around a bit will know that I’ve intentionally used the more static “page” feature of my blog template to accumulate information that I’m picking up from classes and research. To that end, I’ve added the following:

the philosophers / sociologists

I’ve discovered a group of people that aren’t pure historians and who have influenced thought in areas not specific to military history. You’ll only find Auguste Comte there so far but watch for more (interesting fellow – pictured here).

the terms

I’ve got a ton of new words / terminology coming my way and I need a spot to jot them down and eventually define them. I’d also like to be able to go back to them in one spot. It’s looking very highbrow-ish to me now that I’ve added words from today’s reading in Breisach. You, on the other hand, may look at the words and think I must have been sleeping in Freshman general ed classes. OK I knew some of these terms before today!

the railroads

It occurred to me when I did my two posts on the railroads and the American Civil War just how important the rails were to this – arguably – first modern war. Since I also have a page on the ships, I decided to begin collecting railroad information as well. For now it has links to the two railroad-specific post I made last month. More to come.

Kudos

Finally, I’ve add a kudos page which it’s possible is an act of shameful self-aggrandisement but I prefer to think of it as a karmic act of thanks to those folks who have taken the time to make a nice comment either on my blog or theirs. It’s my modest plug back to them and where possible, I provide a link to their site. Thanks to all for the encouragement. And if I missed anyone, I’ll hope to fill in the gaps shortly. Oh and by all means, if you’d prefer I take you name off of this page, do let me know.

Top photo: Auguste Comte. Public Domain. Source: Wikicommons.

Middle photo: Station at Hanover Junction, Pa., showing an engine and cars. In November 1863 Lincoln had to change trains at this point to dedicate the Gettysburg Battlefield. LOC: 111-B- 83.

Book Report: George Bancroft

I realize this won’t be for everyone but I wanted to post the academic book review I finished yesterday on the paperback version of Russel Blaine Nye’s 1945 Pulitzer Prize winning biography George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel. Sadly this book is out-of-print and available only via library or used book markets. It is a fascinating work filled with insights into an uncommon man who was once this country’s most revered historian – but whom most of us have no memory. It also provides considerable information about our country – and indeed the world – in the period leading up to, during and after the Civil War.

It was enlightening to put this post together in that I discovered some great sources of information about many of the people, places and times in which Bancroft lived. Kudos to http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org for their information on important persons in that university’s history.

By Russel B. Nye. New York

(Washington Square Press, Inc.). Pp. 212. 1964. $.60

If biographies written in the twenty-first century tend toward tomes, Russel Nye’s work on George Bancroft, easily the most acclaimed American historian of the nineteenth century, demonstrates how to impress with a modicum of words. Bancroft’s life spanned a period of epic change in the fledgling American nation. Nye skillfully paints a portrait of the man against the sweeping landscape of the United State’s passage from fledgling country at the turn of 18thcentury to a battle-scarred nation ninety years later. Bancroft helped to make American history as politician and statesman. He also became one of the country’s most gifted historiographers and the first popular historian, a title that was, by the end of the century, not unlike his literary writing style, considered “passé.”

George Bancroft came from a legacy of northeastern conservatism. Bred squarely into the center of the American Calvinistic farming culture of Worcester, Massachusetts, his grandfather Samuel Bancroft was both strict Calvinist and independent of mind. Bancroft’s father, Aaron Bancroft, had a noteworthy career as one of the first leaders of the Unitarian movement. This step toward liberalism directed him to the pastorship of a small Second Congregational Church of Worcester and modest means to support his growing family. But it also positioned him with the intellectual elite of New England. The Bancroft home was a place where books were plenty and reading and discussion encouraged. Independent reason was also valued. Aaron Bancroft authored one of the more popular biographies of George Washington, a man who young George Bancroft would eventually count as among the most influential hero-leaders of the country.

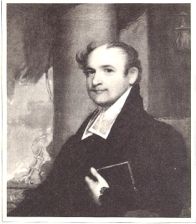

George stood out among his siblings and opportunities were given to him to attend preparatory school at a young age even though it caused strain on his father’s finances. He excelled and passed entrance exams to Harvard College at the  age of 13. Bancroft graduated Harvard at 17 and, with the assistance of college president John Thornton Kirkland (pictured right and papers here), w

age of 13. Bancroft graduated Harvard at 17 and, with the assistance of college president John Thornton Kirkland (pictured right and papers here), w as provided both financial support and the necessary letters of introduction to follow a select few Harvard graduates to Göttingen, one of the top universities in Germany (brief history of the town and university here). His goal was to follow his father into the ministry. He began a rigorous course of study including a self-imposed schedule of sixteen hour days. By the age of twenty, Bancroft had a Göttingen doctorate and the respect of some of Germany’s most noted professors. But he had also developed a considerable interest in philosophy, history and literature and began to doubt whether a career in the ministry remained his passion. He continued with post doctorate studies in Berlin and by the end of his four years in Europe had met many of its influential writers, artists and academics. Bancroft returned home filled with ideas about educational reform and exhibiting mannerisms and dress inspired by his time abroad.

as provided both financial support and the necessary letters of introduction to follow a select few Harvard graduates to Göttingen, one of the top universities in Germany (brief history of the town and university here). His goal was to follow his father into the ministry. He began a rigorous course of study including a self-imposed schedule of sixteen hour days. By the age of twenty, Bancroft had a Göttingen doctorate and the respect of some of Germany’s most noted professors. But he had also developed a considerable interest in philosophy, history and literature and began to doubt whether a career in the ministry remained his passion. He continued with post doctorate studies in Berlin and by the end of his four years in Europe had met many of its influential writers, artists and academics. Bancroft returned home filled with ideas about educational reform and exhibiting mannerisms and dress inspired by his time abroad.

Bancroft spent the next several years trying to find his calling. Trained in philology (the study of languages) as well as theology, he tried on the role of Greek tutor at Harvard but became frustrated with the college’s lack of interest in adopting the new educational techniques he brought from abroad. He was also unpopular as a teacher, which is not to say that he was a bad teacher; rather a demanding one. By mutual consent, he left Harvard after a year and with fellow Harvard and Göttingen graduate Joseph Cogswell, opened the Round Hill School for boys near Northampton, Massachusetts in 1823. It became a phenomenon of sorts due to the melding of the latest methods of European educational reform with those of American boarding school. “It was one of the earliest and most successful efforts of the nineteenth century to raise the level of American secondary education by absorbing the new European experimentation, and served as a powerful influence in the diffusion of new ideas on discipline, individual attention, and stimulation of student interest” (45). A student was treated as an individual with unique learning patterns and cooperated as an equal with his teacher rather than as an inferior with his master. Despite the demanding program, the elite of New England clamored to enroll their sons. With Bancroft as the primary teacher and Cogswell managing administration, the school grew in both size and reputation.

It was at Round Hill School that Bancroft met his wife, Sarah Dwight. Her status as the daughter of a wealthy New England family would ensure his financial independence. Bancroft also continued to work on his poetry (he had published Poems while at Harvard) and found opportunity for preaching. But he was successful at neither. His poetry was labeled amateurish and his oration at the pulpit “too consciously learned, too pretentiously oratorical” (5). Interestingly, Bancroft would become a gifted literary critic. A man of many interests, he became bored with the life of a country school teacher and bowed out of the venture in 1831. The Round Hill School failed three years later.

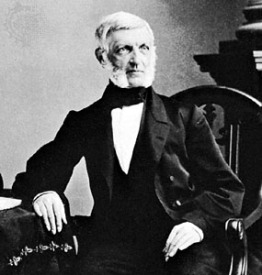

Bancroft discovered while at Round Hill a growing interest in politics. He began to write for prominent journals and even spoke in a political forum in Northampton at the behest of town leaders. In 1830 he was nominated for the Massachusetts’s senate by the Workingmen’s party. Although he declined, his voice as a political philosopher began to emerge. It was firmly centered on the premise that the will of the many outweighed that of the few, a principle that he considered foundational to democracy. He clearly identified himself as a Jacksonian democrat in 1836, a fact that surprised a number of his Whig Harvard colleague s including friend Edward Everett (pictured right). His allegiance was with the common, agrarian masses rather than the privileged minority. His political position became all the more public with Bancroft’s growing involvement in the Democratic Party. He wrote several journal articles in support of Jackson’s position on the national banking issue which he attributed to the long struggle between capitalists and laborers. In 1838, his party work was rewarded with the position of Collector of the Port of Boston. By 1844, he was a prominent player in the Massachusetts democratic delegation and played a key role in securing the Presidential nomination for

s including friend Edward Everett (pictured right). His allegiance was with the common, agrarian masses rather than the privileged minority. His political position became all the more public with Bancroft’s growing involvement in the Democratic Party. He wrote several journal articles in support of Jackson’s position on the national banking issue which he attributed to the long struggle between capitalists and laborers. In 1838, his party work was rewarded with the position of Collector of the Port of Boston. By 1844, he was a prominent player in the Massachusetts democratic delegation and played a key role in securing the Presidential nomination for  James K. Polk (pictured left). Polk appointed Bancroft Secretary of the Navy the following year and he found himself Acting Secretary of War during the months that opened the Mexican War. But Bancroft was after a diplomatic post and between 1846 and 1849 he served as United States Minister to England. It was during this time that he amassed a huge collection of historical notes from British archives, utilizing scribes and secretaries to copy copious amounts of data. These he brought home to America for use in future historical writing.

James K. Polk (pictured left). Polk appointed Bancroft Secretary of the Navy the following year and he found himself Acting Secretary of War during the months that opened the Mexican War. But Bancroft was after a diplomatic post and between 1846 and 1849 he served as United States Minister to England. It was during this time that he amassed a huge collection of historical notes from British archives, utilizing scribes and secretaries to copy copious amounts of data. These he brought home to America for use in future historical writing.

The scholar in Bancroft had found new voice shortly after leaving Round Hill. In 1834, he published the first of what would become his multi-volume treatise, A History of the United States from the Discovery of the Continent (set of all volumes to right). (A full listing of Bancroft’s works avail able online can be found here.) He chose to focus not on contemporary history but rather on the formation and evolution of the nation. Bancroft believed that the creation of the United States of America was part of a divine plan. It was a demonstration for all the world of the efficacy of a nation built on the principles of liberty.

able online can be found here.) He chose to focus not on contemporary history but rather on the formation and evolution of the nation. Bancroft believed that the creation of the United States of America was part of a divine plan. It was a demonstration for all the world of the efficacy of a nation built on the principles of liberty.

Pivotal to the country’s success was the quality of its leaders. “The secret of the science of governing, Bancroft decided, lay in the quality of a nation’s leaders – those great men who personify the people’s ideals, act out their interests, and crystallize their needs in laws and institutions” (82). Nye found that Bancroft valued two types of hero-leaders. The first was the agrarian nobleman best exemplified in Andrew Jackson (pictured below).

His gift was an innate perceptiveness gained from long connection with nature. The second was the classic wise man whose traits Bancroft found in George Washington, a man for whom he had a lifelong admiration.

Abraham Lincoln eventually became Bancroft’s third hero-leader. While initially unimpressed with Lincoln, his respect for him grew to such a degree that he eventually thought him representative of the genius of the American people. Bancroft’s regard for Lincoln was no doubt one reason that he was chosen by Congress to deliver his eulogy. It was considered his best oration.

Like the nation, Bancroft had to come to terms with slavery. He blamed the English for its introduction to the colonies and thought it a temporary evil gone array. Its conflict with the principles of liberty was always obvious. While never a flaming abolitionist, Bancroft considered slavery the primary cause of the Civil War and spoke out about it primarily in his writing. He was a resolute unionist and had little sympathy for arguments for state rights and for the succession movement.

Bancroft happily finished his diplomatic career in Germany where he became a favorite of politicians and intellectuals. He returned to a quite life, still writing and active for most of his ninety-one years. The portrait below was painted while Bancroft was in diplomatic residence in Germany.

Nye does a masterful job of identifying Bancroft’s core beliefs and the influences that formed the man and his career. He also shows a considerable grasp of the nuances of history that were in play in the 19th century, worth noting because Nye’s training is in literature rather than history. His obvious mastery of the large collection of papers Bancroft left behind for his biographers is impressive.

Nye leaves the reader with a sense for the utter brilliance of Bancroft (pictured below in his study) and yet presents him as anything but infallible. He was a man who enjoyed the privileges of an education well beyond the norm of his day and earned by an innate drive and love for scholarship. He was comfortable with life choices that went ag ainst the norm, an indication of independence of thought. He was not unfamiliar with loss, having endured the death of his young wife. He knew failure, having disappointed those who saw in him potential as minister. His failure as a poet, a personal aspiration, revealed a level of sensitivity (He worked very hard to find and destroy every copy of his Poems.). He embraced cultures and perspectives outside of his own and yet remained an American patriot. He brought to his generation a better sense of the story of their country and to a large degree, popularized history. He remained a loud voice for the ideals of liberty and democracy and the rights and privileges of the masses. But at his core, he was, as depicted by Nye, a man of letters and I suspect that Mr. Bancroft would be pleased with that distinction. His legacy is a remarkable body of work sadly forgotten by most citizens of the 21st century.

ainst the norm, an indication of independence of thought. He was not unfamiliar with loss, having endured the death of his young wife. He knew failure, having disappointed those who saw in him potential as minister. His failure as a poet, a personal aspiration, revealed a level of sensitivity (He worked very hard to find and destroy every copy of his Poems.). He embraced cultures and perspectives outside of his own and yet remained an American patriot. He brought to his generation a better sense of the story of their country and to a large degree, popularized history. He remained a loud voice for the ideals of liberty and democracy and the rights and privileges of the masses. But at his core, he was, as depicted by Nye, a man of letters and I suspect that Mr. Bancroft would be pleased with that distinction. His legacy is a remarkable body of work sadly forgotten by most citizens of the 21st century.

American Military University

Rene Tyree

American Historian: George Bancroft

I’m back from Christmas break and trying to recuperate from a few too many cinnamon rolls. Reading assignments and preparation of a research proposal due Sunday are top of mind.

The class is Historiography so the research isn’t to be about the development and proof of a thesis. It’s more about research into the history of how history was written.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

Bancroft was one of the best known American historians of the 19thcentury. While Harvard educated (he entered at 13 and graduated at 17!), he is considered a “literary historian,” who wrote in a style popular with  the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

Perhaps less known is that Bancroft, while Secretary of the Navy, created the Naval Academy. He was also chosen by Congress to eulogize Abraham Lincoln. The New York Times reprinted that Eulogy on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the event in 1915. It, along with drawings of the event, can be seen in their entirety here.

I have located the index to his papers housed on microfiche at Cornell University and two biographies which leverage that material. The first, a two volume set 1971 reprint of M.A. DeWolfe Howe’s 1908 work The Life and Letters of George Bancroft, I was able to find on the Amazon Marketplace in almost pristine shape. The second, George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel, was written by Russel B. Nye and published in 1945. It’s on order. There are other large collections of Bancroft materials in holdings by the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. I’m beginning in earnest a search for articles that deal with his contributions to American history as well.

As a follow-up at some later point, I think it would be very interesting to contrast the style and impact  of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

You might recall that Charles and Mary Beard were the first to suggest that the Civil War was the second American revolution as was mentioned in my previous post here.

The exceptional oil on canvas portrait above of Bancroft in later life was painted by Gustav Richter, a German painter (1823 – 1884). It is a part of the Harvard University Portrait Collection and is on display at Memorial Hall.

More as I get into my research.

Photo credits:

Photo of George Bancroft in middle age taken by Mathew Brady, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo of painting above: The President and Fellows of Harvard College.