Posts Tagged ‘New York Times’

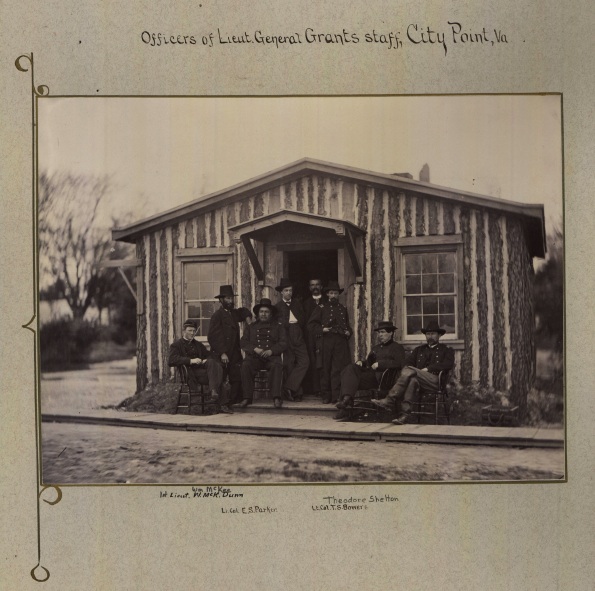

Photo of Lt. General Grant’s Fascinating Staff at Center Point, Virginia

I ran across this excellent photo of Grant’s staff pictured below in City Point, Virginia on the Army Heritage Collection Online site. According to the writing on the matting, included are: 1st Lieut. William McKee Dunn, Jr. (seated left), Lt. Col. E. S. Parker (larger man seated to left of door), and Lt. Col. Theodore Shelton Bowers (standing to right of door). That accounts for only three of the eight men pictured although it’s unclear whether all of the men are in the military. A very similar photo appearing in the book, The Life of General Ely S. Parker, indicates that the building pictured was the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac and was taken in 1864 by legendary Civil War photographer Mathew B. Brady. (1) This would have been one of 22 log cabins that were built to house Grant and his staff and formed the headquarters on the James River. Originally quartered in tents, as the siege of Petersburg extended and the weather deteriorated, Grant had the cabins erected. His cabin had two rooms, one in the front for carrying on war matters and a room at the rear for his quarters. I am unsure whether this is Grant’s cabin. The town is known today as Hopewell. (2)

William McKee Dunn, Jr.: Undoubtedly the youngest of the men pictured, Dunn joined the army at age 18 as a private and became an aid-de-camp to General Sullivan in March of 1863 and then to Grant in October of the same year. He served with Grant through the rest of the war eventually being promoted to captain. Sources indicate that he had occasional charge of Grant’s son Jesse. (3)

Ely Samuel Parker: A highly educated Seneca Indian, Parker was refused entry to the bar and initially entry to the Union Army because of he was not considered an American citizen. He was trained as an engineer and became friends with Grant prior to the war. Grant brought him to his staff at Vicksburg. On August 30 1864, he was officially appointed as Grant’s private secretary by General Order No. 249. Parker eventually rose to the rank of Brevet Brigadier General. He was frequently referred to as simply “the Indian.” (1) His biography is available on Google Books here.

Theodore. Shelton Bowers: On March 8, 1866, the New York Times reported the horrific death of then General T. S. Bowers in an accident while attempting to jump on to the rail car carrying Grant after the party dropped Grant’s son at West Point. You can read that account here. (4)

Sources:

1 The life of General Ely S. Parker: Last Grand Sachem of the Iroquois and Grant’s Military Secretary, Arthur Caswell Parker, (Buffalo, New York: Buffalo Historical Association, 1919).

2 Grant’s Headquarters, a site maintained by the National Park Service accessed on June 28, 2009 here.

3 William McKee Dunn by William Wesley Woolen, (Knickerbocker Press: New York), 93 – 94, accessed online on Google books here, June 28, 2009.

4 “Particulars of the Death of Gen. T. N. Bowers,” New York Times, March 8, 1866, accessed online here, June 28, 2009.

Kudos for the New York Times and Google

I am quite impressed that the New York Times has digitized and made available on the web many of their stories written as far back as the 19th century. I find them extremely useful.

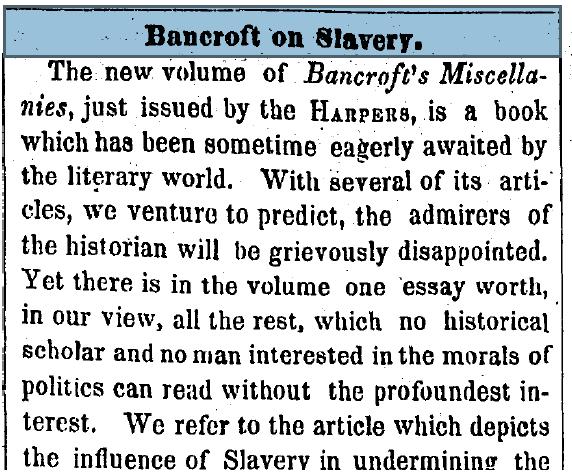

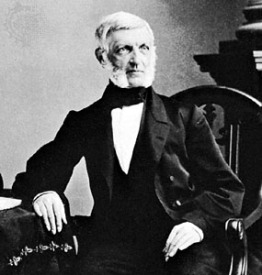

Case in point: In my Historiography class, we are actively discussing German, French and American historians i n the 18th and 19th centuries. George Bancroft , pictured right, (see my earlier post on Bancroft here) is a topic of discussion not only because of his status as the preeminent American historian of the 19th century, but because he was heavily influenced by German thought on – among other things – historiography. One topic led to another and eventually to a discussion about Bancroft’s views on slavery. As it turns out, a review of Bancroft’s then upcoming work Literary and Historical Miscellanies, was published in the New York Times on June 12, 1855 and titled “Bancroft on Slavery.” This was easily found using Google search. One can preview the article here and read it in its entirety in pdf format (see snippet below).

n the 18th and 19th centuries. George Bancroft , pictured right, (see my earlier post on Bancroft here) is a topic of discussion not only because of his status as the preeminent American historian of the 19th century, but because he was heavily influenced by German thought on – among other things – historiography. One topic led to another and eventually to a discussion about Bancroft’s views on slavery. As it turns out, a review of Bancroft’s then upcoming work Literary and Historical Miscellanies, was published in the New York Times on June 12, 1855 and titled “Bancroft on Slavery.” This was easily found using Google search. One can preview the article here and read it in its entirety in pdf format (see snippet below).

How cool is that? I’m sure the New York Times derives benefit from the advertising placed even in their archives section. I’ll put up with a few ads to not have to travel to the library and look up articles on microfiche.

THANK YOU to the good folks (whoever you are) who made this decision at the New York Times. Oh and THANK YOU Google Books for making Bancroft’s Literary and Historical Miscellanies available online in its entirety as well. Now if we can only get more dissertations into Google Scholar.

American Historian: George Bancroft

I’m back from Christmas break and trying to recuperate from a few too many cinnamon rolls. Reading assignments and preparation of a research proposal due Sunday are top of mind.

The class is Historiography so the research isn’t to be about the development and proof of a thesis. It’s more about research into the history of how history was written.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

For my research paper, I plan to explore the influence of historian George Bancroft (right) on Antebellum, Civil War, and Postbellum American history. I may need to shave this down a bit depending on how much material I find.

Bancroft was one of the best known American historians of the 19thcentury. While Harvard educated (he entered at 13 and graduated at 17!), he is considered a “literary historian,” who wrote in a style popular with  the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

the public. His primary work was the multi-volume History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, which he began writing in 1830. [Picture left of remaining vHe published the first three volumes over that decade. The final set would be ten volumes. A first revision was completed and published as six volumes in 1876 as part of the national centennial.

Perhaps less known is that Bancroft, while Secretary of the Navy, created the Naval Academy. He was also chosen by Congress to eulogize Abraham Lincoln. The New York Times reprinted that Eulogy on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the event in 1915. It, along with drawings of the event, can be seen in their entirety here.

I have located the index to his papers housed on microfiche at Cornell University and two biographies which leverage that material. The first, a two volume set 1971 reprint of M.A. DeWolfe Howe’s 1908 work The Life and Letters of George Bancroft, I was able to find on the Amazon Marketplace in almost pristine shape. The second, George Bancroft: Brahmin Rebel, was written by Russel B. Nye and published in 1945. It’s on order. There are other large collections of Bancroft materials in holdings by the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. I’m beginning in earnest a search for articles that deal with his contributions to American history as well.

As a follow-up at some later point, I think it would be very interesting to contrast the style and impact  of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

of George Bancroft with Charles and Mary Beard. As a historian friend of mine said, “you’d be hard pressed to find two more different expositors on the American experience than Bancroft and Beard. Bancroft was an unabashed patriot and advocate of democracy, to a degree that would be considered embarrassing in most academic settings today. Still, he was indeed the most articulate and widely-read of our early historians, and his writings both reflected and helped to create the sense of American exceptionalism that has prevailed for most of our history as a nation.”

You might recall that Charles and Mary Beard were the first to suggest that the Civil War was the second American revolution as was mentioned in my previous post here.

The exceptional oil on canvas portrait above of Bancroft in later life was painted by Gustav Richter, a German painter (1823 – 1884). It is a part of the Harvard University Portrait Collection and is on display at Memorial Hall.

More as I get into my research.

Photo credits:

Photo of George Bancroft in middle age taken by Mathew Brady, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Photo of painting above: The President and Fellows of Harvard College.